Blood, sweat and sexual chemistry: How Fred and Ginger mesmerised audiences

Ahead of the BFI’s Fred & Ginger Day next month, which pays tribute to the famous movie dance duo as part of a Ginger Rogers season, Geoffrey Macnab looks back at the couple’s movie magic – achieved, despite their off-screen tensions, through sheer hard work and sizzling sexual chemistry

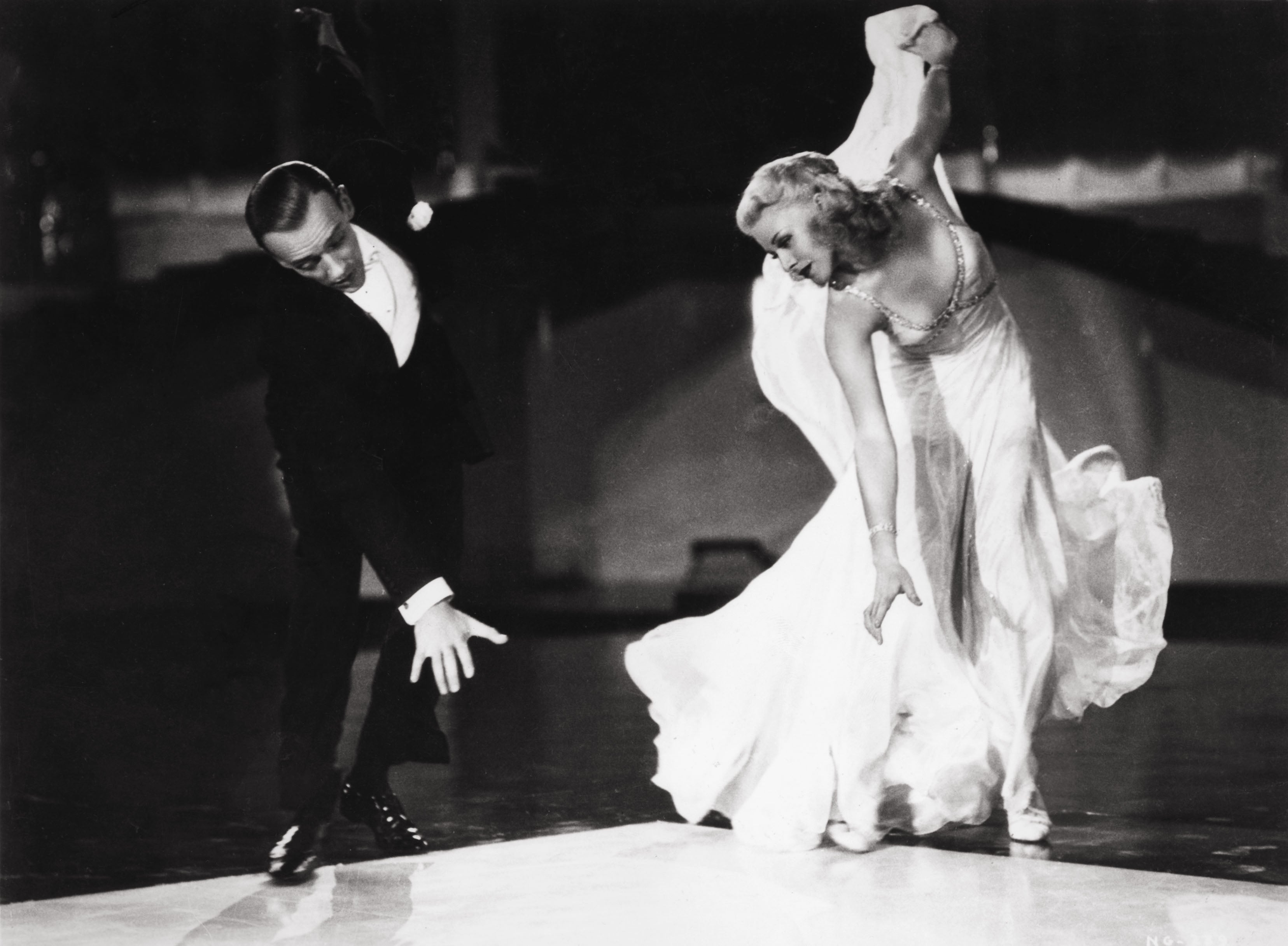

It’s the blood in the slippers that gets you every time. When Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire were shooting the dramatic “Never Gonna Dance” sequence at the end of their 1936 film, Swing Time, they did 48 takes. This is a dance of desperation and longing. Astaire and Rogers are playing sweethearts whose love affair seems to be ending. He has just discovered she is supposed to be marrying somebody else. On screen, the dance seems effortless. Astaire is in his white tie and top hat. Rogers – the subject of a month-long retrospective at the BFI later this month – is in a glittering ball gown. He serenades her and then they begin to whirl around the empty nightclub floor. There’s next to no cutting – “either the camera dances or I do”, Astaire famously used to tell his directors – but the two stars appear as if they’re enjoying themselves as they waltz, twirl, and pirouette their way up a staircase.

Years later, in her 1991 autobiography, Rogers revealed the full strain behind what was one of the most glorious set pieces in the 10 movies she made with Astaire. The sequence took an eternity to get right. If there was the slightest hiccup, they had to start again. At one stage, an arc light went out. At another moment, the camera made funny noises. Sometimes, the dancers lost their rhythm. Worst of all, at the end of what had been a perfect performance by the two leads, Astaire’s toupée suddenly flew off.

Rogers was a hardened professional. “I never said a word about my own particular problem. I kept on dancing even though my feet really hurt. During a break, I went to the sidelines and took my shoes off: they were filled with blood. I had danced my feet raw.” Audiences watching the film may regard that beatific smile on Rogers’s face in a different light if they know the agonies she was enduring.

The following year, when she and Astaire did a roller-skating sequence in Shall We Dance (1937), they skated for more than 80 miles. It was little wonder she used to joke to the press after films with Astaire that she was going to take a holiday – “digging in the salt mines”.

Why did Rogers and Astaire work so well on screen together? “She gave him sex and he gave her class,” Katharine Hepburn famously suggested. That was certainly part of the equation but there were other factors too. Her height helped. She was 5ft 4.5in tall. Astaire was 5ft 9in and far more comfortable with her than with his other, taller co-stars. They were both relentless. He was a perfectionist while she was known as one of the hardest-working stars in Hollywood.

Astaire didn’t like kissing his leading ladies, certainly not when his first wife Phyllis was around on set. Nonetheless, a couple of years before they appeared on screen together, he and Rogers had gone on a date and had ended up snogging in the back of a car. Rogers writes in her autobiography about a kiss that lasted for five minutes and would “never have passed the Hays Office [censorship] code”.

She also admitted: “If I had stayed in New York, I think Fred Astaire and I might have become a more serious item. We were different in some ways but alike in others. Both of us were troupers from an early age, both of us loved a good time, and, for sure, both of us loved to dance.”

In the Rogers and Astaire movies, there was often sexual tension between the two leads. The characters they played tended to be very different. Only on the dance floor would their initial hostility and misunderstandings be overcome. The rival stars weren’t above trying to make each other slip up. For the “Cheek to Cheek” routine in Top Hat (1935), when Astaire is singing “heaven, I’m in heaven”, he was reportedly struggling very hard not to sneeze. She had deliberately chosen to wear an extravagant dress covered in ostrich feathers, so audiences would look at her as well as at him. If the feathers prompted an allergic reaction in her dance partner, that was his problem.

A new biopic starring Margaret Qualley as Rogers and Jamie Bell as Astaire promises to lift the lid on what the trade press are calling the duo’s “passionate and explosive relationship” in films. Tom Holland is also slated to play Astaire in a rival biopic, although there is no news yet about who will be his Ginger. The fact that there are two such projects in the pipeline testifies to the couple’s enduring appeal.

However, the current BFI season of Rogers’s films is trying hard to move Rogers out from under the shadow of Astaire. After all, their collaborations make up only a small part of her overall career. She made more than 60 films without Astaire, appearing in dark backstage dramas and screwball comedies, as well as in musicals. Patrick McGilligan, one of her earliest biographers, writes of her “astonishing versatility”. She could play everything from office clerk to flapper, and chorus girl to heiress. She was both wildly glamorous and very down to earth, a potent combination that turned her into one of the biggest box-office draws of her era.

Rogers could do bawdy as well as innocent. In her early film, The Young Man of Manhattan (1930), in which she co-starred as the flirtatious flapper Puff Randolph, her memorable Mae West-like one-liner, really caught on with audiences. “Cigarette me, big boy!” The star wasn’t afraid to take on offbeat projects either. In Billy Wilder’s very subversive The Major and The Minor (1942), Rogers, who had just won an Oscar for Kitty Foyle (1940) and was at the peak of her fame, played a woman living in New York who pretends she is a 12-year-old girl, so she can get a cheap train ticket home to Iowa. The twist here is that a Major (Ray Milland) falls for her even though he thinks she is a kid.

Rogers was excellent as the wise-cracking and ambitious chorus girl Anytime Annie in 42nd Street (1933) who’ll do whatever it takes to get a role (“she only said ’no’ once and then she didn’t hear the question”), and very funny opposite Cary Grant in wartime screwball comedy Once Upon a Honeymoon (1942) playing a gold-digging ex-burlesque dancer pretending to be a blue-blood socialite. She is almost as well known for the films that she didn’t make as the ones that she did. She turned down the lead role as the female reporter Hildy Johnson in Howard Hawks’s His Girl Friday (1940), thereby giving Rosalind Russell the best part she ever played.

Few other stars of her era, then, had as rich and varied a career as Rogers. Even so, everything always eventually boomerangs back to her dance films with Astaire. The BFI itself is holding a Fred & Ginger Day on 8 April.

The Rogers-Astaire partnership began partly by chance in 1933 with the musical, Flying Down to Rio. They weren’t the main stars. Rogers was hired only after Dorothy Jordan, originally cast in her role, left the production to marry its producer Merian C Cooper, who was best known for making King Kong. Astaire thought she looked awful in the film and asked not to be paired with Rogers again but their sultry, wildly energetic, forehead-to-forehead “carioca” routine together stole the movie.

The couple’s musicals are so cherished that the sometimes troubling sexual politics in the films are overlooked. It’s disconcerting today to watch a film like Carefree (1938) in which Astaire plays a psychoanalyst who anaesthetises, hypnotises, and ultimately steals his best friend’s fiancée (Rogers). Early on, Rogers hears a recording in which Astaire describes a patient as a ”typical pampered female...what she needs instead of a doctor is a good spanking”. The film ends with Rogers being socked in the face by her fiancé.

Miles Eady, film writer and curator, is giving an illustrated talk on the “magic” of Rogers and Astaire during the BFI’s Fred & Ginger Day. He acknowledges that Carefree is not the type of movie that would be made today.

“It is quite a problematic film…[it] taps into that assumption by the audience that he [Astaire] was the controlling, creative force. You have some very difficult themes within the film. There is a bit of violence toward Ginger and she goes down the aisle with a black eye at the end,” Eady says. “The expression of the satire and parody of romance is hugely sexist [by the standards of] today.”

There are other Rogers-Astaire scenes that will stick in the craws of contemporary viewers. For example, in Swing Time, Astaire wears blackface to portray legendary tap dancer, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. There are moments in his dance sequences with Rogers in which he’ll block her path or grab her wrists. “It’s presented as playful fun but to us it is problematic,” notes Eady.

Nonetheless, Eady remains a huge fan of the musicals and believes that they can still inspire and entertain younger audiences. “When you talk about the difficulties of the entire films, the sexual politics etc, actually the way forward seems to be extracting the stunning moments out of the films and sharing those,” he says, citing online clips like “Old Movie Stars Dance to Uptown Funk” that put the Astaire-Rogers routines to funk music – and strip out the troublesome plot lines.

Critic Pamela Hutchinson, who will present a free introduction to Ginger Rogers for members of the BFI’s 25 and under scheme next month, makes a similar point. “Ginger Rogers had this very youthful, vibrant quality … the dance sequences from her films play so beautifully on YouTube that I am sure lots of people find her work that way.”

The films, then, may display attitudes that seem horribly dated but those bravura sequences for which Rogers bled for her art, and which Astaire rehearsed with such demonic intensity, remain as fresh as ever. The harder they worked, the more graceful and effortless Rogers and Astaire’s dancing seemed to become on screen – and that is why it is still so cherished today. Astaire was a genius but arguably Rogers was even better. After all, as a Bob Thaves cartoon she used to keep framed in her house proclaimed, she “did everything Fred Astaire did but backwards and in high heels”.

‘Ginger Rogers: All That Sass’ runs at BFI Southbank from 27 March to 30 April. Fred & Ginger Day is on Saturday 8 April. Tickets are available from bfi.org.uk/ginger

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments