Pixies’ Doolittle at 30: How songs about suicide, psychopaths and mutilated eyeballs sparked a new rock generation

The band’s first top 10 UK album was no mere indie rock breakthrough record, says Mark Beaumont. It was the seed from which decades of febrile rock brilliance would sprout

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

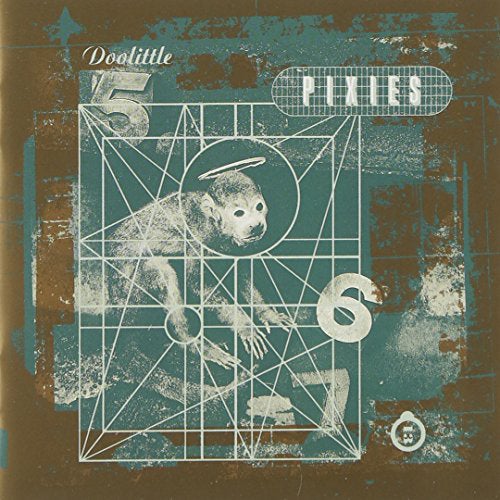

Your support makes all the difference.At first glance, you’d worry for a world influenced by Pixies’ Doolittle. Songs about suicide, psychopaths, ecological disasters and mutilated eyeballs, delivered in a series of unholy screams, hisses, wails and growls. Sleeve images seemingly found in a serial killer’s scrapbook: human teeth lining the rim of a rusty bell, a dissected crab, horse hair curled around a spoon laid on a naked female torso. And its iconic cover, a halo-clad monkey hemmed in by quasi-religious symbols and numbers, was like a sepia snapshot from the cell of a sacrifice.

Yet influenced it was. Surfer Rosa, the 1988 debut album from these deceptively harmless-looking Boston college kids, had enraptured the music press and launched the underground cult of Pixies, with its dark, abrasive production courtesy of Steve Albini and its savage yet sweetly melodic songs pitting themes of incest, deformity, sexual abuse and violence against fun tunes about interracial sex (“Gigantic”), boy-next-door superheroes (“Tony’s Theme”) and existential snorkelling holidays (“Where Is My Mind?”).

But it was the 1989 follow-up Doolittle that turned the band into generational figureheads, as “Debaser” tore up the indie club dancefloors, “Monkey Gone to Heaven” crept seditiously into the US rock charts and the signature quiet/loud dynamic of tracks such as “Gouge Away” and “Tame” embedded itself into the burgeoning grunge scene – Kurt Cobain would famously claim that “Smells Like Teen Spirit” was his attempt at writing a Pixies song. Released 30 years ago today and giving Pixies their first top 10 UK album, Doolittle was no mere indie rock breakthrough record; it was the seed from which decades of febrile rock brilliance would sprout.

Albini has claimed that Pixies were a malleable, easily influenced band during the recording of Surfer Rosa (although he’s been kinder about the sessions more recently) and for all the fire and brimstone in those early records, you can hear a touch of naivety. Frontman Black Francis, aka Charles Thompson IV, was a University of Massachusetts dropout fresh from an formative exchange trip to Puerto Rico when he moved to Boston and begged his former U-Mass roommate Joey Santiago to start a band with him in 1986.

Within a week they had a bassist when Kim Deal was the only person to answer their small ad for someone into both Hüsker Dü and Peter, Paul and Mary, and got the job despite never having played bass before. Drummer Dave Lovering, suggested by Deal’s husband, had played in a couple of local bands before joining, but none of the band that hit Fort Apache studios in March 1987 to record 17 demos of Francis’s songs – raw, rabid alt-pop songs with a distinct flamenco flavour and lyrics inspired by his experiences at U-Mass, his trip to Puerto Rico and his upbringing in the Pentecostal Assemblies of God church – were exactly hard-bitten studio veterans.

The reception that met 4AD’s 1987 compilation of eight of those demos, Come On Pilgrim, and their debut album proper the following year, plus some hard global touring, had clearly instilled confidence, however. Pixies hit Doolittle with the wind in their soiled, sordid sails. “We were still young and fresh, but starting to kind of know what we were doing,” Francis told Esquire in 2014. “When we were done with the demos I think Joey and I felt that, ‘Oh yeah... something big happened.’ We felt confident.”

“We went to a practice space and [it’s like] we were arranging a flower arrangement,” Santiago told Yahoo of their intense rehearsal period, “that’s what we came up with and thought was perfect. And it made it to the albums … People should perceive that as how natural we sound. When we practised, that’s what we whittled it down to. We really worked on sounding simple.”

These were some pretty thorny flowers. When Throwing Muses and Echo & the Bunnymen producer Gil Norton, selected for the project after working on a more commercial single version of “Gigantic”, arrived in Boston and sat Francis down in his apartment to play through the songs on an acoustic guitar, it must have felt like scouting out an exorcism.

“Debaser”, a frantic, frivolous ode to Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel’s 1929 surrealist short film Un Chien Andalou, focusing particularly on the scene in which a woman’s eye is sliced open with a straight razor. “Tame”, a slavering, bloodthirsty diatribe against drunk Boston college girls. “Wave of Mutilation”, a surf grunge ditty concerning El Niño and ruined Japanese businessmen driving off piers into the sea with all their family strapped in the back seat. “Hey”, a seductive boudoir R&B song obsessed with prostitutes, inspired by rumours Francis had heard about his parents; “ancient stories from when they were younger”, Francis told Esquire.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

There were gruesome remodellings of biblical and classical mythologies called “Gouge Away” (Samson and Delilah), “Dead” (David and Bathsheba) and “Mr Grieves” (Neptune’s daughter). And all these religious, nautical and ecological themes were drawn together in one dark, cult-like piece of ritual noir pop called “Monkey Gone To Heaven”, culminating around the ominous preacherman bark of “If man is five, then the devil is six… and if the devil is six then God is seven!”

The album’s working title? Whore.

“I never thought he was crazy,” Norton tells me. “You’re with Charles and he’s very charming so you never feel intimidated by him. The thing I learnt in that period was that he doesn’t like to repeat himself so you have to try to find ways of exciting him into doing things. There’d have to be a reason to repeat a part… I was frustrating him because a lot of the songs were quite short – a minute and 20; very rarely did they get over two minutes.

“They were great ideas for songs but they didn’t feel like they’d been fleshed out, to me. I was trying to do that and Charles got a bit frustrated on day two; we went around to Tower Records and he pulled out Buddy Holly’s greatest hits and said, ‘Look Gil, look at this’. And he turned it over – if you look at Buddy Holly’s greatest hits, most of the songs, if he gets over two minutes with one it’s a bit of an epic.”

They were great ideas for songs but they didn’t feel like they’d been fleshed out, to me

They weren’t the walkover that Albini painted them as, then? “Charles was pretty opinionated,” says Norton. “I always think of Kim as the cool factor, so she’s always got a good opinion about what she wants and what she doesn’t like. They weren’t a walkover, but the thing I like about good bands is they’ll listen and try things and see where it leads them. By the time they got to that point they’d done quite a lot of touring and a couple of albums and their confidence as a band was maybe a bit bolder.”

Two weeks of pre-production rehearsals later, Pixies entered Downtown Recorders studio in Boston in October 1988, according to Santiago, “very ready”. For two weeks, they hammered home a song a day. Yet there was still space for the odd in-studio surprise. Wanting to record “Hey” as live as possible, Francis was forced to record his vocal in a cupboard to avoid being drowned out by the drums: “It was a really small broom cupboard,” says Norton. “He had to play the guitar with the neck facing up to the ceiling while he was playing and singing it live. I was so happy when we got a take of that that I was pleased with.”

During mixing, Norton also managed to convince Francis to include one thing on the album that wouldn’t be “portable”; a string section on “Monkey Gone to Heaven”. “We ended up hiring a string section from the Symphony Orchestra up there,” Norton chuckles. “They rocked up in their full evening dress – the girl wore a big long black dress and the boys had dickie bows. I remember Charles going ‘wow, this is amazing’.”

Other Pixies had revelations, too. Santiago found a frenzied staccato attack on “Dead” that he decided to adopt as his go-to style. “That’s when I found something – I finally found it,” he told Yahoo. “[I thought] ‘That’s one of the formulas I’m gonna stick to’.” And given the chance to sing lead vocals on “La La Love You” as a “Ringo thing”, Lovering unleashed his inner Rat Pack crooner. “He’d never sung and he was really nervous going, ‘I don’t know how to do this Gil’,” Norton recalls. “I said, ‘Let’s just try it Dave, it’ll be a bit of fun’. Once he started he was like Frank Sinatra. He started hamming it up – you couldn’t stop him once he got going.”

They savoured the weird and wonderful undercurrents of the album they’d sensibly retitle Doolittle midway through, but some of the more popular songs troubled them. “Here Comes Your Man” was a tune Francis had first written on a piano at the age of 14, and it had gone through many versions and variations since, none of them satisfactory. “[Gil] sped it up,” Santiago told Alt Press. “Before it was more of a country song, and we were kind of hesitant about making it that way. It came out very, very poppy, and we refused to play it; we never played it until the reunion ... Like Charles said, he’s from Liverpool, and they have a tendency to get hits out of you.”

When they did start playing the song live, Francis found it amusing that his sarcastic commentary on the misery of homelessness was so widely misunderstood. “It’s a world that’s dark and edgy inhabited by hobos,” he told Esquire. “It’s like a dark David Lynch movie. I guess I get a lot of satisfaction when people are pumping their fists in the air and singing like it’s some sort of simple love song – which would be fine, because there’s nothing wrong with simple love songs – but this is not that.”

“Debaser”, meanwhile, almost didn’t even make it onto the record. “At one point [Charles] didn’t want it on the album,” says Norton. “I was like, ‘You’re joking, this has got to go on the album, it’s one of my favourite songs’. With the backing vocal, I came up with that with Kim, we wanted to find a really good part for her to sing. I wanted to keep a really long note like on ‘Lovely Day’ by Bill Withers.”

“Musically, it is what it is,” Francis told Esquire. “I’m not even sure how I feel about that song. Sometimes I really enjoy playing it, sometimes I find it... I’m on the fence with it.”

Doolittle was no fence-sitter’s album, though. It was an album of magical and mysterious pop tunes, often tripping over themselves to reach the next hookline, but shrouded in a crepuscular, menacing, close and corroded atmosphere. The mythologies inherent in the songs lent the album a sense of dark ancient mysticism, the violence and ecological portents gave it a very present air of danger and Francis’s unhinged deliveries spoke of a melodic master turned malevolent. It was as dark as Pixies would get and set their definitive tone and aesthetic – the best Beach Boys album ever made, losing its mind after months trapped in a psychopath’s well.

“I didn’t go in there deliberately to do that,” says Norton. “I always think of those sort of albums as a rollercoaster ride, once you got on it you don’t want to get off because it twists and turns in all these different directions. That’s why there are 15 songs or whatever on there – they’re not very long so it’s really nice that they’re like blasts of events, I suppose.”

Norton plays down the rising tensions in the Doolittle studio. Legend has it that Deal was frustrated at being sidelined as a songwriter and Francis wouldn’t allow her a front-seat role; her only writing credit on the album is as co-writer of the ruined country ballad “Silver”. Things would later come to a head on the subsequent F**k or Fight tour – Deal and Francis chose to fight, with Francis even throwing a guitar at Deal onstage in Stuttgart. The result was Deal’s seminal spin-off supergroup The Breeders, and a widening schism within Pixies that would ultimately prove fatal for their first era.

But not before they’d wrapped up their menacing masterpiece. “At the very, very end, on the last night of recording I was flying out, the band had left to go home and I was in the studio by myself for one night,” Norton recalls. “I had the cassette and I put it on and I remember listening to it thinking ‘this is gonna be a bit of a classic album’. I didn’t realise the longevity of it, but I thought ‘we’ve created something a bit special here’.” Santiago felt the same way: “We knew we had something special going on,” he told Alt Press.

Subsequent generations of fans and musicians concurred. Far beyond Doolittle’s formative influence on grunge and Nirvana’s breakout success, the record spawned imitators across the rock spectrum. You can hear it snarling in the background of the early works of Radiohead, mid-period Blur, Pavement, Weezer and PJ Harvey, and time has embedded it at the root of modern alt-rock, from Arcade Fire to Jack White, Wolf Alice and Idles. And according to Santiago, the new waves of wannabe debasers keep on coming.

“When we played the Doolittle tour [in 2009],” he told Alt Press, “and not only the Doolittle tour, but I would say since 2004, since we reformed – when you look out into an audience, the majority of it I would say is kids that weren’t even born when our records [were out], and they know every song, they sing every word… 10 years later – there are still the kids coming who are that age relatively, 14, 15 years old, who have heard about us and know all the songs. It’s fantastic. We’re a very fortunate band.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments