Nirvana’s former manager: ‘Claims that Kurt Cobain was murdered are ridiculous. He killed himself’

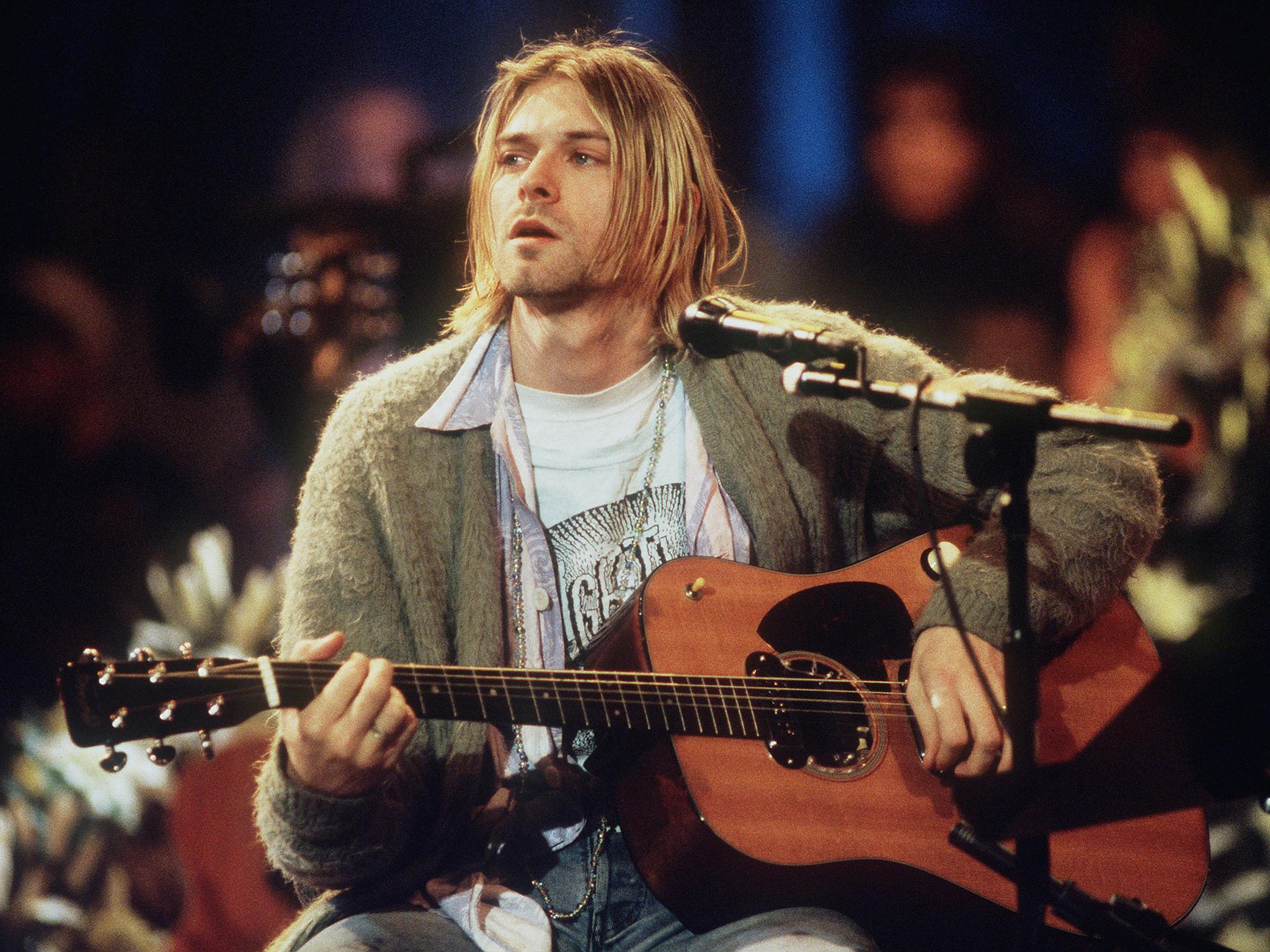

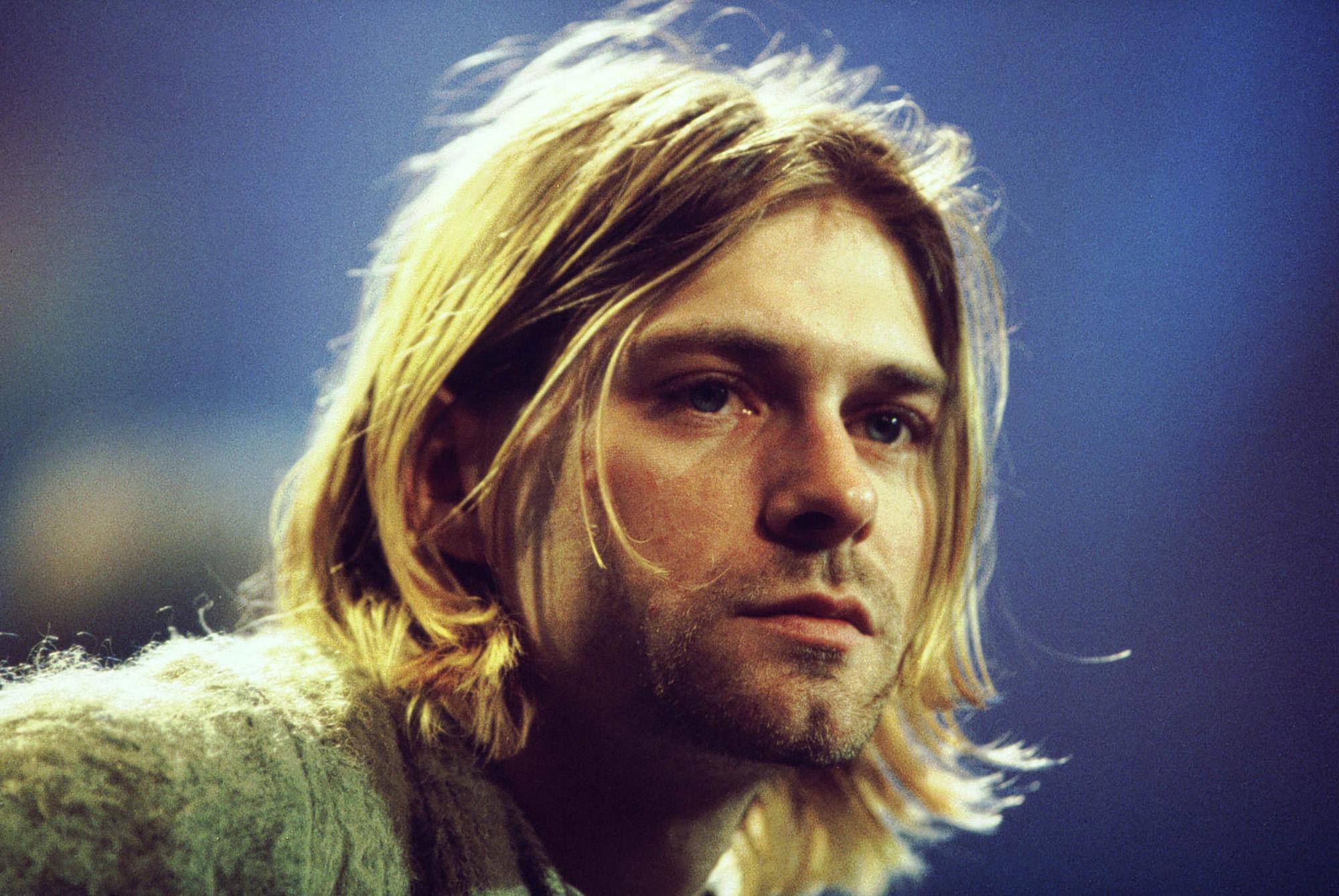

Twenty-five years since the death of one of the most influential musicians of all time, Mark Beaumont speaks with former Nirvana manager Danny Goldberg about Kurt Cobain’s last moments, his relationship with Courtney Love, and his fondest memories about his time with the band

On 25 March 1994, Nirvana’s former manager Danny Goldberg joined nine other people at 171 Lake Washington Boulevard in Seattle to beg for Kurt Cobain’s life. They had all been invited by Cobain’s wife Courtney Love as part of an intervention over Cobain’s spiralling depression and drug abuse, but each would have known how high the stakes were. Three weeks earlier, he had overdosed on champagne and Rohypnol in Rome, which Love would claim to be his first suicide attempt. The previous week police had been called to the Seattle house, where Cobain had locked himself in a room with several guns and a bottle of pills. As each of the friends, industry associates, counsellors and bandmates present – Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic was there, alongside live guitarist Pat Smear – urged Cobain to get clean, get help and get on with living his charmed-yet-cursed life, they knew they were running out of chances.

Glassy-eyed, increasingly angry and feeling – in Love’s words – “ganged up on”, Cobain wouldn’t crack. He insisted he needed a therapist rather than rehab, and began flicking through the Yellow Pages to find one. At one point he fled to an upstairs bathroom when management associate Janet Billig began flushing his prescription drugs, fearing a second overdose. When Goldberg – who had been one of Nirvana’s managers throughout their peak years and was now a trusted confidante and adviser – told him to quit heroin for good, Cobain complained about feeling trapped by the constant attention of being one of the most famous rockstars in the world, and argued that, if William Burroughs could live a long and creative life as a junkie, why couldn’t he?

“He was in a bad way,” says Goldberg, fresh from reliving the experience in his new book on managing Nirvana, Serving the Servant. “The main memory I have is feeling so shitty about how hard it was for me to get through to him and how deeply depressed he seemed to be. It was not a great situation in terms of connecting with him personally because there were so many other people there and I’m sure he felt under siege in his own house. But Courtney was scared. She’d witnessed that he was going through a very tough time and thought maybe other people talking to him would get him to get some help.

“I spoke to him on the phone when I got home and talked to him one last time. I couldn’t shake him out of being depressed, I couldn’t cheer him up or get him to feel there was hope. I was just hoping that if the drugs got out of his system then he could think more clearly and that would be a good time to have better conversations with him. Of course I never was able to have such conversations.”

In fact, the intervention did have the desired effect, albeit briefly. On 30 March, Cobain checked into the Exodus Recovery Centre in LA, where he discussed his personal and drug problems with counsellors, seemed positive to visiting friends and spent time with his daughter Frances Bean for the last time in his life. Then, the day after checking in, he jumped over the perimeter fence, flew back to Seattle and went missing – despite several sightings, a concerned Love hired a private detective to track him down, focusing on staking out his drug dealer’s apartment. Neither he nor Hole guitarist Eric Erlandson – whom Love had asked to check the house for Cobain – thought to look for him in the greenhouse above the garage. His body was discovered there on 8 April by an electrician arriving at the Lake Washington Boulevard house to install a security system, lying beside a shotgun he’d bought from his friend Dylan Carlson before leaving for LA. It’s believed he took his life on 5 April, 25 years ago today.

Like those that took JFK, Martin Luther King Jr and John Lennon, it was a shot that echoed around the world. As Serving the Servant rightly assesses, Cobain was more than just a musical phenomenon, the king of grunge and the man who sent the underground US punk scene stratospheric – Nirvana’s second album Nevermind has sold more than 30 million copies and its lead track “Smells Like Teen Spirit” is among rock music’s most celebrated anthems, declared the best single ever by NME in 2014. He wasn’t just the guy who mashed accessible melody with gnarled guitar filth and struck jackpot. He was also the ultimate icon for tormented outsiders everywhere; the empathetic, kohl-eyed brother in hurt all the damaged indie rock punks never had, staring directly into their souls.

“It’s that combination of darkness, idealism, humour, compassion, cynicism,” Goldberg argues. “The totality of it connected so intimately with fans they felt that they weren’t the only crazy people, somehow there were these [musicians] that were popular that understood them. That was his gift.”

Serving the Servant paints Cobain as a deeply conflicted character. He could be kind and sullen, confident and despairing, funny and argumentative, generous and deceptive, sarcastic and romantic, charismatic and deeply ordinary. When Goldberg first met him, at a meeting six months before the recording of Nevermind – he’d been encouraged to manage Nirvana by John Silva, his partner at Gold Mountain Entertainment, and Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore – he found Cobain something of a shrinking violet, but assertive when it came to his career.

Cobain was determined to leave the independent Seattle label Sub Pop, which had released their debut album Bleach in 1989, and record their second album on a major, opting for Geffen, home of their scene mentors Sonic Youth. As a fan of both Big Black and The Beatles, Cobain didn’t share the hardcore punk underground’s rankled disgust at the idea of overground success, and his determination to adapt punk’s DIY ethics and intensity – where the artist conceives and controls the image, artwork and videos every bit as much as the music – for mainstream adoption was what Goldberg considers his driving characteristic.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

“He had this borderline obsessive focus on his art,” he says. “He was completely focused on his career in every way, he cared about every detail of it and was intent on accomplishing the best of what he could do. He had a lot of other things going on in his mind, he had personal demons and personal sweetness, but he was first and foremost an artist.”

Inside a year of taking the band on, Goldberg had a phenomenon on his hands. “Smells Like Teen Spirit” snowballed across global rock radio; the riff that launched a million moshes. Here was a song that took the abrasive attitude and sludgy guitars of the Sub Pop scene, applied the quiet/loud jumpscare pop jolt that had been perfected by Boston’s noir rock subversives Pixies and repackaged it with an instant melody and gravelled vocal that the Guns N’ Roses fans could understand. Lyrically, it was surreal and ungraspable – “A mulatto, an albino, a mosquito, my libido, okaaaay” – but when its parent album Nevermind arrived two weeks later, Nirvana’s unique aesthetic cohered. Where much of the Eighties punk underground raged against the machine and Pixies ranted about Biblical violence, college culture and incest, Nirvana found their anger in a desolate, self-destructive ennui familiar to millions of broken slacker teens. The grunge generation was born.

There’s an impression from the book that, though Cobain always planned to be a major rock icon, he struggled with it happening so fast. “Once ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ was on the radio it was like a rocket ship launching. There was no precedent for it, coming from the punk rock culture that had incubated his personality as an artist. It was a powerful experience and one with mixed blessings in terms of how it affected everyone involved personally, and Kurt being the songwriter and lead singer got a disproportionate amount of the intensity of that. It’s disorientating for anybody, the visibility and the suddenly widened set of tools you have. And also the fact that you’ve spent many, many years wanting something and now you have it and it didn’t solve every single inner problem.”

Did he change after Nevermind knocked Michael Jackson off the US No 1 spot? “No, he was the same guy. He was intellectually very prepared to be a public figure, it wasn’t like an overnight thing. But there was no question that within a few months heroin made an appearance.”

Goldberg’s book is sympathetic towards the splashdown of Love in Cobain’s upended world (“he fell in love… this wasn’t a transient rock’n’roll fling but a deep connection”), but recognises that the sudden presence of a “strong-minded, enormously talented artist in her own right and an enormously complicated person” in the Nirvana camp at such a pivotal time shifted the dynamic. After several years of flirting from afar, Love’s pursuit of Cobain becomes a full-blown relationship late in 1991. There are moments of intense, insular romance, disruptive tiffs and drug buddyism. Although Goldberg is careful not to blame Love for Cobain’s drug-taking, what begins as bonding over cough syrup turns into a revival of his previous dabblings in heroin.

He’d heard reports, but Goldberg first noticed Cobain withdrawn and barely able to stay conscious after an appearance on Saturday Night Live in January 1992. The next day he set about organising an intervention involving label associates, doctors and drug counsellors in LA to press both Love and Cobain to undergo detox, particularly since Love had just learnt she was pregnant. “There were seven or eight of us that confronted them at Cedars Sinai hospital. It was pretty much ‘please, don’t do this to yourselves, this is not good for you’. It was quite a clear emotional plea from everybody, forcing them to realise that it was not an invisible problem … The short-term results were within a month or two they both seemed clean and in a good frame of mind. But Kurt continued to struggle with drugs for the rest of his life, on and off. There was no silver bullet for him.”

Cobain’s sporadic addictions were a tangled psychological web. “There was part of him that hated himself for doing heroin,” Goldberg believes. “He felt guilty about it and also felt particularly bad that it was publicly known, it was a bad example to his fans, and there was part of him that just was in so much pain and that was apparently one of the things that could address it, both the emotional and physical pain. It was a constant struggle. But he wasn’t stoned all of the time, he was clean a lot of the time, he was very creative a lot of the time, he was a very kind person a lot of the time. He was complicated.”

Danny separates three stages of Cobain into “before Nevermind”, “the immediate aftermath” and “the dark side”. The final two years of his life were notoriously turbulent. A 1992 Vanity Fair article by Lynn Hirschberg suggested that Love was using heroin during her pregnancy, causing the newlywed couple to fight for custody of Frances Bean and instilling in Cobain a distrust of the press that would verge on paranoia: “A lot of artists will hear 99 compliments and one criticism and obsess on the criticism,” Goldberg says. “Kurt had a little bit of that tendency in him.” Yet there are reports of boisterous backstage food fights and the band setting fire to dressing room sofas, and Cobain parodied his reported issues at Nirvana’s legendary Reading Festival headline set that year.

“He took the anguish he was feeling and the unresolved issues about custody of his daughter and the embarrassment of the way he and Courtney had been depicted and turned it into this performance art,” Goldberg remembers. “Being pushed onstage in a wheelchair and hospital gown, then leaping up like James Brown and, with intense blazing energy playing an incredible set and asking everyone in the audience to say, ‘I love you Courtney’. He was not depressed all the time, he was creative, he was funny, he was warm, he was all of these things – it depended on which day or which hour of the day or which period of time which Kurt you were gonna get. Humour was a big part of it – they were simultaneously the hardest rocking band around and able to make fun of the idea of being the hardest rocking band, both manifesting rock’n’roll and deconstructing it at the same time. It was always part of the essence of Nirvana, It wasn’t unrelentingly dark, it was a combination of dark and light.”

Indeed, at the same time that the band were humorously baiting one-time fan turned arch nemesis Axl Rose into an abusive tantrum at the 1992 VMA Awards, they were also taking a serious and uncompromising approach to third album In Utero. Inspired by his work with Pixies and The Breeders, Cobain chose celebrated punk maverick Steve Albini to produce the record in just 14 days, creating a bleak, scabrous slab of hardcore noise rock that many consider their real masterpiece.

“The sheer success of [Nevermind] made it by definition ‘commercial’,” Goldberg argues. “Kurt was conscious of the attitudes of a lot of people in the punk rock community so he wanted to do something different... Albini had a technique of recording that created more of an intimate feeling, as if the band was in the room with you as the listener.”

When Cobain asked Scott Litt to remix the album’s singles “Heart-Shaped Box” and “All Apologies” to bring his buried vocals to the fore, Albini attacked Nirvana’s team in the press as manipulative and parasitic: “Every single other person involved in that band’s career was a piece of shit,” he said. “There are people who were in Nirvana’s camp who will think ‘he can’t be talking about me’. I’m talking about them. Those people lied to my face, lied to the band’s face, took advantage of the band’s naivety and got them hoodwinked into signing ridiculous deals, embezzled money from them, made them pay for absurd bullshit.” Was he talking about Danny?

“He’s a good self-promoter,” Goldberg retorts. “I admire some of his records. I’ve never met him to this day. Everyone’s entitled to make a living. Kurt controlled every aspect of that record as he controlled every aspect of the previous record and every detail of Nirvana’s career, so the idea that there were other people influencing or controlling what Kurt did as an artist is not true. Kurt had 100 per cent creative control legally and also morally. No one was gonna argue after Nevermind with any decision he made. He was the boss, he was the visionary… he made the record he wanted to make.”

Despite its clear intention to see off the brainless jock element of Nirvana’s audience, the sort of guys that would’ve been beating the band up in high school, In Utero sold in its millions in 1993. Yet Goldberg took a step back at this second peak, taking a role as a record company exec en route to becoming president of several US major labels. “I loved Kurt and was so proud of what Nirvana accomplished, and I liked the other guys too, but I was nervous about its fragility, especially after understanding that there were drugs around.”

He watched Cobain’s final downward spiral as a close associate, friend and adviser. His repeated unsuccessful attempts at rehab, his phoned threats to potential biographers he was suspicious of (Danny was “horrified” that Cobain would do such a thing), his drug meltdown backstage at the recording of Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged in New York performance in November 1993, his overdose in Rome. All of it made Goldberg, when the end finally came, wearily dismissive of the “conspiracy theories” that claim Cobain was murdered.

“It’s ridiculous,” he asserts. “He killed himself. I saw him the week beforehand, he was depressed. He tried to kill himself six weeks earlier, he’d talked and written about suicide a lot, he was on drugs, he got a gun. Why do people speculate about it? The tragedy of the loss is so great people look for other explanations. I don’t think there’s any truth at all to it.”

Shortly before his death, Goldberg confesses, Cobain had asked him if he might be able to launch a career outside of Nirvana. He’d even arranged to record with REM’s Michael Stipe and bought the plane ticket, but never showed up. Had he lived, Goldberg surmises, he might have been his generation’s Neil Young, always burning out and never fading away. “I think he would’ve found different ways of expressing himself, sometimes with the band and sometimes not.”

It’s all too easy to fantasise about the music that a major rock star didn’t live to make, but Cobain’s legend is rooted in far more than simply dying young. In his few short years at the helm of 20th-century rock music he upended the machismo, cockiness and lurid lasciviousness of the genre and ushered empathy, sensitivity and emotional depth to the fore, saving rock from the grunts and the jocks. It’s him we have to thank for every inclusive, compassionate rock band from Paramore to Idles – and for making Motley Crue irrelevant, we are forever in his debt.

Goldberg, too, sees Cobain alongside the true legends of music. “He’s one of the greats. He’s somebody that touched people very deeply and very widely, which is a handful of people. Bob Marley’s on that list, John Lennon, Dylan, Edith Piaf, John Coltrane, Billie Holiday. He’s on that list of the greats.”

His fondest memory? Goldberg doesn’t even pause.

“I keep coming back to thinking about his smile,” he says. “There was something about the look in his eyes at certain times that was so beautiful, both amused and loving at the same time, that’s what I come back to.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments