Bad Moon Rising at 35: How Sonic Youth’s 1985 masterpiece reinvented indie rock

Recorded in a studio overlooking a polluted canal, the alternative band's second album sprang from humble beginnings. But, writes Ed Power, it was the record that helped them discover their place in the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The end of Sonic Youth is a story lit up in a blaze of tabloid headlines. In 2011, Kim Gordon, the band’s bassist and custodian of its avant-garde flame, separated from her husband, Sonic Youth singer and guitarist Thurston Moore, after she discovered he was having an affair with a much younger woman. As their relationship foundered, so did the alternative pop institution they had started together in 1981.

In her 2015 memoir, Girl in a Band, Gordon recalled the numbness she felt playing Sonic Youth’s final show, at a festival in Sao Paulo.

“It reached a point… where I always said something on stage,” she wrote. “But I didn’t… I didn’t want our last concert to be distasteful when Sonic Youth meant so much to so many people; I didn’t want to use the stage for any kind of personal statement, and what good would it have done anyway?”

But enough about the end. What about the beginning? In June 1990, there was Goo, their hugely resonant blending of accessible alternative pop and proto-grunge, on which Gordon sang about Karen Carpenter and collaborated with Public Enemy’s Chuck D (neither exactly par for the course for an underground band in the early Nineties). And there was Daydream Nation in 1988, considered one of the era’s most important post-punk records (opening number “Teenage Riot” recently surfaced in a Marc Jacobs fragrance ad, of all places).

And then there was Bad Moon Rising, their first masterpiece, released 35 years ago. Its influence rumbles on to this day. You can hear it in the thoughtful din of newcomers such as Goat Girl, Fontaines DC and Dream Wife. Often artists may not even be aware of their debt to Sonic Youth. The singular blend of art-punk chaos and gripping melodies has become part of the gene pool of forward-facing indie music.

Bad Moon Rising was not their debut LP, though – not officially at least. That honour lies with Confusion is Sex, a scratchy 12-inch from 1983 that captured Sonic Youth in a protean state. At that point, they weren’t writing songs so much as stitching together collages of noise. It is a start but not an arrival.

For that reason, Bad Moon Rising is considered by many to be the first true Sonic Youth album. It was fully realised, forged amid the grime of Eighties New York. It is also, very loosely, a conceptual piece about America, rock’n’roll and original sin.

This was all more or less spelt out by Moore, Gordon, guitarist Lee Ranaldo and soon-to-be-departed drummer Bob Bert (replaced by Steve Shelley on 1986’s EVOL). Bad Moon Rising was, after all, named after Creedence Clearwater Revival’s classic slice of American gothic from 1969. The song “Ghost Bitch”, meanwhile, is a rumination by Gordon on the Land of the Free’s first mortal transgression, the dispossession of Native Americans.

“Our founding fathers laid right down,” she coos. “And Indian ghost from long ago/ they gave birth to my bastard kin/ America is it is called.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

The concept of a thread of evil running through American history resurfaces on the final track and the first classic Sonic Youth anthem, “Death Valley ’69”. The tune is a galloping duet between Moore and punk poet Lydia Lunch that digs into the Manson murders, the disastrous Rolling Stones Altamont concert and the death of Sixties idealism.

Propelled by Moore’s snarling vocals, it is raw and unflinching – a before-the-fact rebuttal of the wish fulfilment of Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time In Hollywood, which imagined an alternate universe where Sharon Tate survives that awful night.

“I heard them say they liked Neil Young, which surprised me,” Bad Moon Rising’s producer Martin Bisi tells me. “Neil Young was there maybe as a guilty pleasure if it came on radio. I knew they like that stuff. And they were very Sixties aware, getting into the Charles Manson thing. In some ways, relative to everything else in New York, they were kind of like a country band.”

“We definitely were a bit fixated on the end of the Sixties,” agrees drummer Bob Bert. “With Manson, Altamont and the flower power movement turning dark.”

Bisi’s BC Studio was – and still is – located in a former Civil War armament factory overlooking Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal. The canal is one of the most polluted waterways in North America (arsenic levels are 60 times higher than safe exposure levels). He opened it in the early Eighties, with Brian Eno and avant-garde musician Bill Laswell.

Eno, David Bowie’s old mucker and later hit whisperer to U2 and Coldplay, had at that point been living in New York for several years. He’d become enthusiastic about the city’s No Wave scene, the dissonant and somewhat nihilistic movement that had evolved out of New York punk. In 1978, he had recorded the semi-legendary album No New York – a showcase for No Wave’s brightest talents (though this had ultimately damaged the scene, with several groups miffed at being omitted).

Bisi, meanwhile, had a hip-hop background, having collaborated with Afrika Bambaataa and assisted Laswell on the 1983 Herbie Hancock hit “Rockit”. Twelve months before that, again at BC Studios, he had recorded New Jersey band Memories and their new vocalist, a 19 year-old singer named Whitney Houston.

Sonic Youth sought Bisi out for two reasons. He charged $500 a week – a bargain in New York at the time. More importantly, his background in hip-hop appealed to a group eager to move beyond their associations with No Wave.

“They wanted to distinguish themselves,” says Bisi, sitting in the same studio where Bad Moon Rising was recorded. “They were claiming they’re not No Wave, they’re not experimental.

“They came to want to work with someone in hip-hop. People really admired it had the time. It had credibility, the way punk did. Like punk and hardcore, it was ‘do it yourself’. They like the idea. They would tell people they were working with a hip-hop producer.

One of Sonic Youth’s signatures was their use of modified instruments. They would stick screwdrivers under the strings to achieve a distorted effect or put a metal rod in the middle of the guitar (a technique picked up from Moore’s mentor, avant-garde composer Glenn Branca). On Bad Moon Rising, this approach is most discernible on the foghorn that blasts at the start of “Ghost Bitch” – in reality Ranaldo manipulating an acoustic guitar.

“I’m very proud of it, says Bert of Bad Moon Rising. “Whenever I play it, I’m never disappointed. So many people have told me that it is their favourite Sonic Youth album. I wouldn’t do a thing different. Someone once said ‘Loveless’ by My Bloody Valentine wouldn’t exist without Bad Moon Rising. I don’t know if that’s true but [MBV leader] Kevin Shields once told me that he is a big fan of the album.”

Today, Bisi’s studio shares the neighbourhood with a Whole Foods supermarket, a craft brewery and an artisan ice-cream parlour (popular scoops include “visions of peppermint”, “lemon poppyseed” and “maple bourbon barrel”). Things were very different in 1985. There was no artisan ice-cream, no maple bourbon barrel.

“The whole environment was sketchy,” says Bisi. “A lot of the sketchiness, you took as routine. It’s similar to now [and the pandemic] in a way. You take all these precautions. When I venture out today I take care to put on my mask and have gloves that are disinfected. You make it part of your routine.

“Back then, you would do stuff like walk down the middle of the street and avoid sidewalks. Occasionally you stopped to look behind. Or you would avoid entire blocks. It did not seem strange to basically not take the subway after 10pm. Or to never take it alone.

“It was always in the background. I got mugged within four or five months of moving here. We would see the muggers around. One of them would even call out to me, or to his friends. ‘Hey, there’s the guy.’ You would head the other way and they would think it was funny.

There was also the mafia. “I would see they sketchy older wise-guys, that I guess looked like they had been in a boxing match, with their noses squashed in. ‘Okay, I wonder how many people you put in cement galoshes.’”

Sonic Youth he remembers as thoughtful and quiet. Later, they would gain a reputation as the hippest of the hip and ultimate adjudicators of cool. Their cheerleading more or less rescued the reputation of The Carpenters and brought underground talents such as songwriter Daniel Johnston and a young Nirvana to a wider audience. And yet, behind that air of studied insouciance, they could be surprisingly traditional, which set them apart from others in New York post-punk.

Drugs were not part of their lifestyle. Moore, from suburban Connecticut, and Gordon, daughter of a Los Angeles academic, had had a traditional white wedding in 1984, presided over by a priest, with Gordon’s father giving her away. The wigged-out experimentation they saved for their music.

“There’s always this thing about Sonic Youth being this cool band,” Thurston Moore would tell me years later. “It’s like ‘Sonic Youth – you’re sooo cool’. You know, when I was growing up, I was the geek. At school I was a total nerd. I was the dork. So to actually become part of something that’s looked upon as an arbiter of cool is so weird for me.”

“I remember how little they spoke,” says Bisi. “Kim at the time was not very vocal in the studio. That doesn’t mean she wasn’t saying stuff after the sessions. In the studio she would say very little.”

One of the few occasions he recalls her becoming animated was when a piece in The New York Times hailed Sonic Youth as leaders of No Wave. As Bisi remembers, they were determined not to be perceived as arriving on the coattails of the scene and of pioneers such as Suicide and DNA.

“They were being compared or discussed along with Arto Lindsay from DNA,” Bisi remembers. “Arto also does skronky guitar. And I remember Kim being pissed off about being associated. She was saying the only similarity was geographical. It seemed strange to me because it was a good piece of press. So who cares?”

Sonic Youth were without a label at the time. They’d been burned more than once in their dealings with independent record companies in the US. Perhaps that is why they had so few misgivings about signing to Geffen Records in 1990, which figures such as punk producer Steve Albini accused of behaving in a “distasteful” fashion.

“When we were on some indie labels, a lot of times the label was learning as they went,” Gordon said in 1992. “And they didn’t have the resources we enjoy now. We don’t work for [Geffen subsidiary] DGC, we work with them.”

Major label interest was however thin on the ground as they toiled over Bad Moon Rising. Their saviour was a sometime band manager and promoter from Sheffield named Paul Smith.

Several years previously he and some associates had established a music video imprint called Doublevision. He knew Lydia Lunch, who sent him a five-track demo tape of the Bad Moon recordings. He was smitten on the spot. And when it proved impractical to put out the album on Doublevision, Smith skipped two mortgage payments on his house.

With the money he set up a new label, Blast First, and pressed five thousand copies of Bad Moon Rising. Blast First would later release albums by Dinosaur Jr, Butthole Surfers, Afghan Whigs and the Mekons. But it all started with Sonic Youth and Bad Moon Rising.

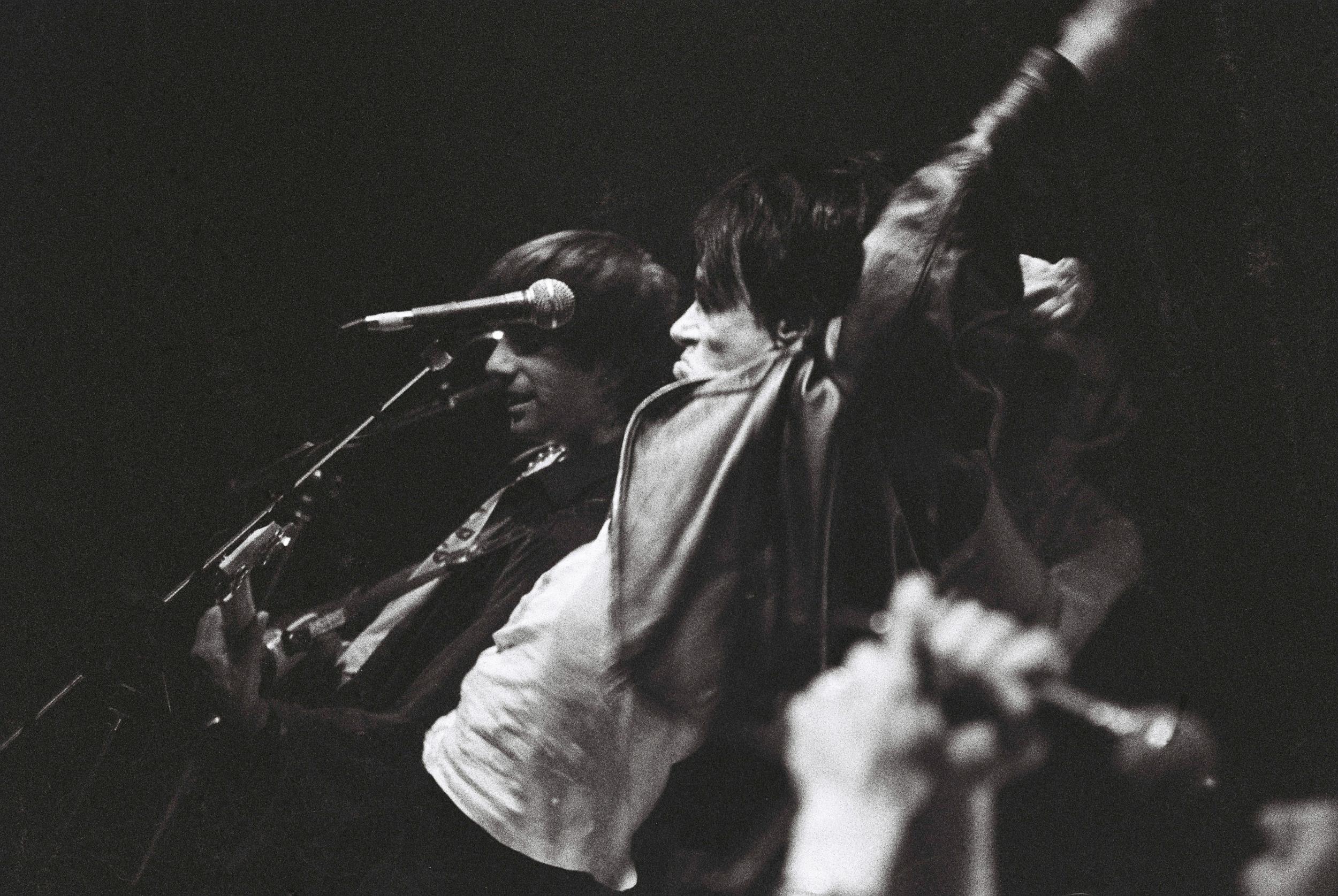

The band didn’t have much time to mull over their accomplishments. In early April, they flew to the UK to support ex-Birthday Party hell-raiser Nick Cave, who was going on the road with a new band called The Bad Seeds. The tour began on 16 April at 900-capacity Coasters in Edinburgh and concluded at Hammersmith Palais on 28 April. That final gig went a lot better than their first London date in 1984, when their equipment malfunctioned and Moore smashed it up in frustration.

“That was a great experience,” recalls Bert. “It was Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds’ first tour and they had Rowland S Howard on guitar [Howard would soon afterwards split from Cave owing to “creative differences” and form These Immortal Souls].

“They had a bunch of fans that followed them on that tour, There was one goth girl who was front and centre every night. Every time Nick threw down a cigarette, she would light one and hand it to him. The last show of the tour was in London. Everyone was backstage, Mark E Smith, the newly formed Jesus and Mary Chain, a wasted Jeffrey Lee Pierce [of the Gun Club] in a fringed leather outfit.”

Bad Moon Rising was cautiously welcomed rather than heralded as the beginning of one of the most inspiring chapters in American rock. Alternative newspaper The Village Voice rated it a “b”; the Boston Phoenix offered qualified praise of “Death Valley ’69”, which it described as “more like a disfigured rock song than the result of primal-scream therapy”.

Still, Sonic Youth had found their place in the world. Twelve months later, again working with Bisi, they would release the sprawling, dreamlike EVOL. In 1988 came their definitive musical statement, Daydream Nation. And then, a few years after that, Geffen, on Sonic Youth’s recommendation, signed Nirvana. “Smells Like Teen Spirit” was unleashed on an unsuspecting mainstream and rock music turned head over heels.

To claim all that flowed from the Gowanus Canal and Bad Moon Rising would be an overstatement. Yet Bad Moon Rising undoubtedly lit a spark. It was the start of something bigger than Sonic Youth.

“The fact that 120 Minutes on MTV or the whole alternative music movement would come along wasn’t even a thought,” says Bert. “It still blows my mind that Sonic Youth [are] still being talked about in 2020. I would have never imagined that they would go on so long.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments