Kim Gordon: ‘You can’t really forgive someone if they don’t say they’re sorry’

The former Sonic Youth frontwoman talks to Alexandra Pollard about her debut solo record, the dissolution of her 29-year marriage to Thurston Moore, and why the music industry is full of ‘entitled men who don’t realise there are boundaries’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

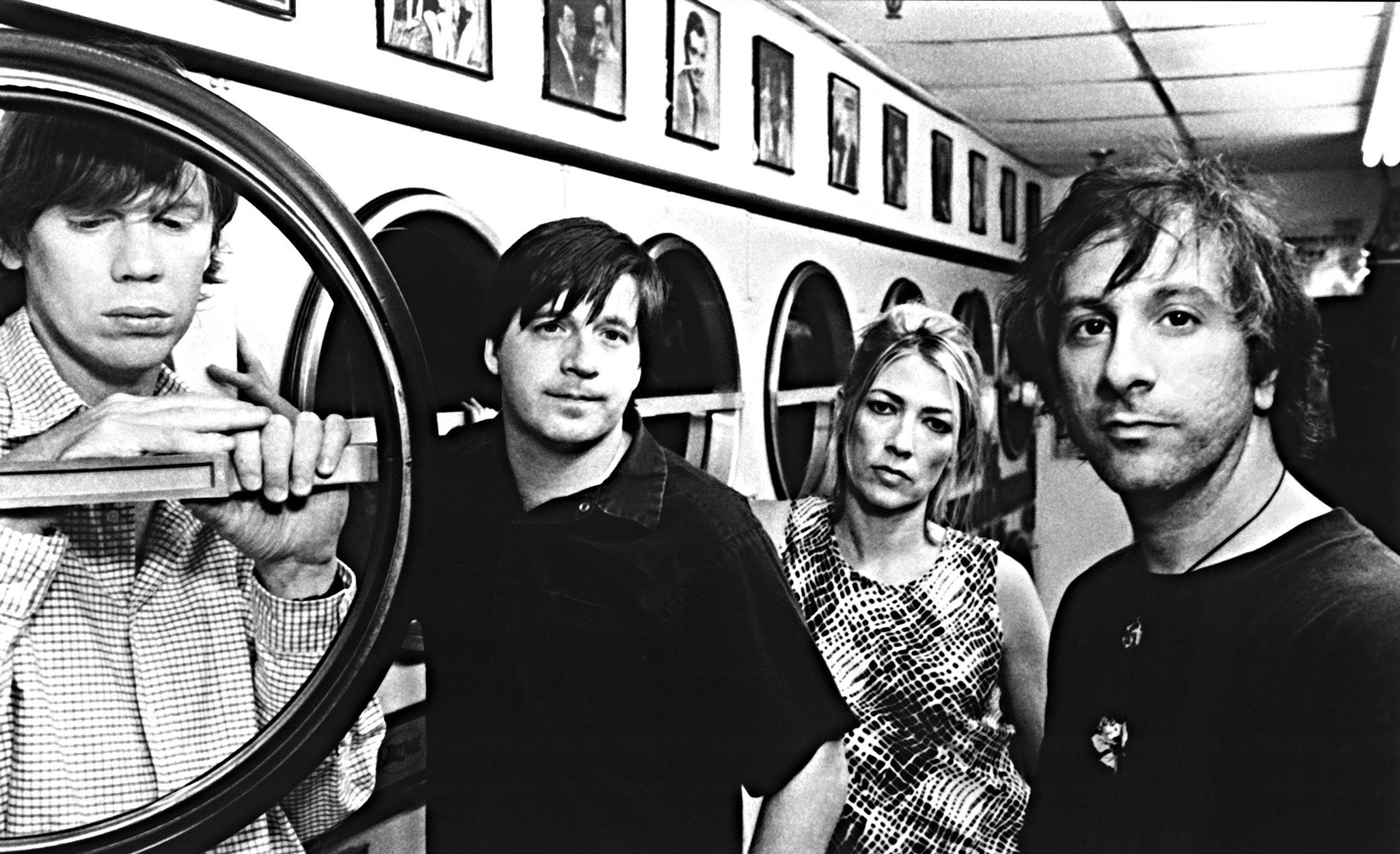

Your support makes all the difference.The Dalai Lama said you don’t have to forgive someone if you can have empathy for them. And if the Dalai Lama said it…” Kim Gordon, former bassist and frontwoman in the totemic alt-rock band Sonic Youth, is discussing the breakdown of her 29-year marriage to Thurston Moore.

At the height of their powers, she and her former bandmate were the avant-garde scene’s equivalent of a Hollywood power couple, defying the rock’n’roll cliché of nihilism and infidelity, and raising a child, Coco, together. Then, in 2013, he had an affair with a much younger woman. They split up. And so did the band.

It started, wrote Gordon in her astonishing 2015 memoir Girl In A Band, “in slow motion, a pattern of lies, ultimatums, and phoney promises, followed by emails and texts that almost felt designed to be stumbled on, so as to force me to make a decision that he was too much of a coward to face. I was furious. It wasn’t just the responsibility he was refusing to take; it was the person he had turned me into: his mother.”

“I mean, if you loved someone, you can try to understand them,” the 66-year-old Californian says now of Moore’s affair, finally settled on a firm chair in a London hotel, having rejected two other seating options as too “sunken”. “You know, I empathise, but at the same time, you have to protect yourself from trauma and getting hurt again.” I suppose the expectation of forgiveness is thrust upon women more than men, I suggest. “Right. Well, you can’t really forgive someone if they don’t say they’re sorry.”

For a while, she and Moore were unstoppable. Emerging as part of New York’s no wave scene in the Eighties, equal parts insolence and insouciance, Sonic Youth became the sound of early Nineties counter-culture. Founded by Gordon, Moore, and Lee Ranaldo, the band played in guitar tunings they couldn’t name, each instrument clashing and crashing together to create something both artless and artistic. Not for nothing did Nirvana’s bassist Krist Novoselic – even after Nevermind had sent the Seattle band stratospheric – say that they simply wanted “to do as good as Sonic Youth”.

“When we first started, I guess there was something called indie pop that we weren’t part of,” says Gordon. “For some reason, we thought of ourselves as a rock band. The things that were important to us were The Velvet Underground, Alan Vega, The Stooges, Alice Cooper. The bar was set very high.”

They managed to reach that bar. After winning over both underground rock fans and the music press throughout the Eighties, the band managed to drag their avant-garde sensibility towards the mainstream without ever losing an ounce of kudos. In 1989, they signed to a major label, having been convinced that they could retain complete creative control, and they released perhaps their most beloved album, Goo, a year later. “Kool Thing”, that record’s lead single, is a stomping, sardonic masterpiece, in which Gordon transmutes an awkward encounter with LL Cool J into a freewheeling rumination on class, race and gender.

“Rock was the sound of rebellion,” she says of that time, “but it’s not anymore. I mean, indie-rock’s nice, but it’s not really impactive.” Why is that? “Um, I have no idea. In America, if you’re white, your life is much more comfortable in every way, so maybe there’s not enough reason to rebel. Revolutions don’t happen when people are comfortable. I don’t know why punk rock happened, actually. People got sick of corporate music, I guess.”

As far as Gordon is concerned, hip hop is the new punk rock. “Punk is an attitude,” she says, “I identify as punk, even though I was never a punk. It’s just a whole way of seeing the world, of being an outsider and wanting to go against the grain. Hip hop is kind of like punk rock in that way. You don’t have to have musical chops, it’s about ideas and an attitude. Cardi B. There’s something punk about her. Or Lizzo. These women who are really ruling the scene.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

It’s these women, not two-a-penny indie-rockers, who inspired Gordon to make her first ever solo album, No Home Record, 38 years into her career. The record came about by accident. “I’d done one song with Justin [Raisen],” she says. “I just started fooling around with this drum machine, recording little snippets of guitar, trying to figure out how to incorporate Seventies drum machine stuff into a solo gig. Anyway, then I started thinking…”

She brought in Raisen, who has worked with Charli XCX, Angel Olsen and Sky Ferreira, to produce the whole album. She worked with him, she said, because he understood her “trashy, dissonant” sensibility, and the record is both of those things and more. Combining industrial, noise and post-punk with 808s and minimalist electronic beats, it is poppy and potent, its snipped, disjointed lyrics not easily penetrable, though they traverse subjects such as sex, capitalism, harassment and curated utopia. It came out last week to rave reviews.

“I’m surprised by how well it’s been received,” says Gordon. Why? “Because I didn’t really think about it. I think the record’s kind of eccentric. The music isn’t something you listen to as much as experience, and the things I’m talking about are not easy to digest.” There’s another reason. “A lot of solo records kind of suck,” she says, laughing. “So I wasn’t in a rush to do it. There’s so many expectations people have. So many Sonic Youth fans. Nothing is gonna be as impactive as the band was.”

None of the people walking past us today seem to notice that an icon is in their midst. Gordon doesn’t exactly make a scene. Dressed in a fringed jacket, her blonde hair in a long, angular bob, a gold thin spike around her neck, she is still and quietly spoken. Though clearly not concerned with shows of artificial affability – “I dunno, that’s a weird question,” she shrugs if I ask something she doesn’t deem worth answering – she seems more shy than taciturn. “When men are aloof, no one says they’re cold,” she said in a recent interview. “They say they’re cool.”

Gordon has spent most of her career being treated differently because of her gender. In 1991, Sonic Youth toured with Neil Young on his Ragged Glory tour. “They thought we were freaks,” she would later recall, “mainly because I was a woman onstage and they always thought I was going to get hurt. It just aligned me with the whole rock thing – they’d throw a birthday party for somebody and there’d be a stripper on the side of the stage. I remember the stage manager yelled at me once because I was over there: ‘You’re distracting Neil.’”

It wasn’t just Gordon’s presence that disrupted the macho norm of rock music, but her lyrics, too. “Swimsuit Issue”, from 1992 album Dirty, tackled sexual harassment at a time when few bands were doing so: “Don’t touch my breast, I’m just working at my desk / Don’t put me to the test, I’m just doing my best.” When Gordon wrote that song, she says, “it wasn’t topical. It was embarrassing because we’d just signed to Geffen where this A&R guy was exposed as sexually harassing his secretary. I think they wanted the story to go away.” She describes No Home Record’s “Hungry Baby”, which is written from the point of view of a lecherous male musician, as an “update” on that song. “Now it’s like, topical. People are talking about it now. I felt like because I had written one 30 years ago, I could write this.”

Does she think the music industry’s due its #MeToo moment? “Well, there have been some things that have come out,” she says. “I mean, it’s prevalent in the culture. Even if it’s not a sexual thing where some higher-up comes on to you, if it’s emotional, it’s still gonna make you feel weird and not able to do your job. I’m sure things will come out more. The music industry is so… the sexism is so ingrained in it, on every level, that it’s unbelievable. How do you pick it apart? It’s honestly so old-fashioned. You can see that at the Grammys. When I went to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony, it was all these old white guys there. I was like, ‘This is so weird.’ But I don’t really follow the music industry. Obviously, I saw the one about Ryan Adams.”

Earlier this year, Adams was accused of sexual misconduct and emotional abuse by a handful of women, including his ex-wife Mandy Moore, the singer Phoebe Bridgers and an underage girl referred to as “Ava”. When I interviewed Jenny Lewis, who worked with Adams on several albums, and had previously spoken of him as “needling” her in the studio and of having to “submit” to him, she said his behaviour “is not something I’ll ever tolerate again”.

I mention Lewis’s experience to Gordon, as an example of the non-sexual but still damaging power men can yield over women. “But that’s like, a personality thing,” she says. “It is definitely ingrained – I know it is in me. You’re so used to a man being in a position of power, or looking up to one, so it’s just as much her problem as it is his problem. But that’s kind of ingrained in being a woman. Wanting to please. It perpetuates this cycle with these entitled men who don’t actually realise there are boundaries. I’m not saying she’s wrong to feel that way, but there’s a point where you have to draw the line.” It’s difficult, I say, when society teaches women to acquiesce. “Yeah, I’m not saying that it’s our fault as women for doing that, but at the same time, the subtle grey areas that go on outside of sexual harassment are hard to break.”

Gordon dissected these grey areas in Girl In a Band. Writing it wouldn’t have occurred to her, she says, if she hadn’t been approached by editors. But she’s glad she did it. “I never really felt like I wanted to open myself up to interviews for rock magazines,” she says. “Like, why would I want to do that? And then I thought, ‘Well, I guess I’ve been saving it, so now I have to write it.’ It’s a different feeling, being able to create a space for yourself that you didn’t feel was there before.”

And after all this, having written a well-respected book, released a successful solo album, and changed the shape of rock music, does she feel like an outsider? “Oh yeah,” she smiles. “But I don’t want to be an insider.”

‘No Home Record’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments