The naked pleasures of Women in Love – why Ken Russell’s misunderstood film is a masterpiece

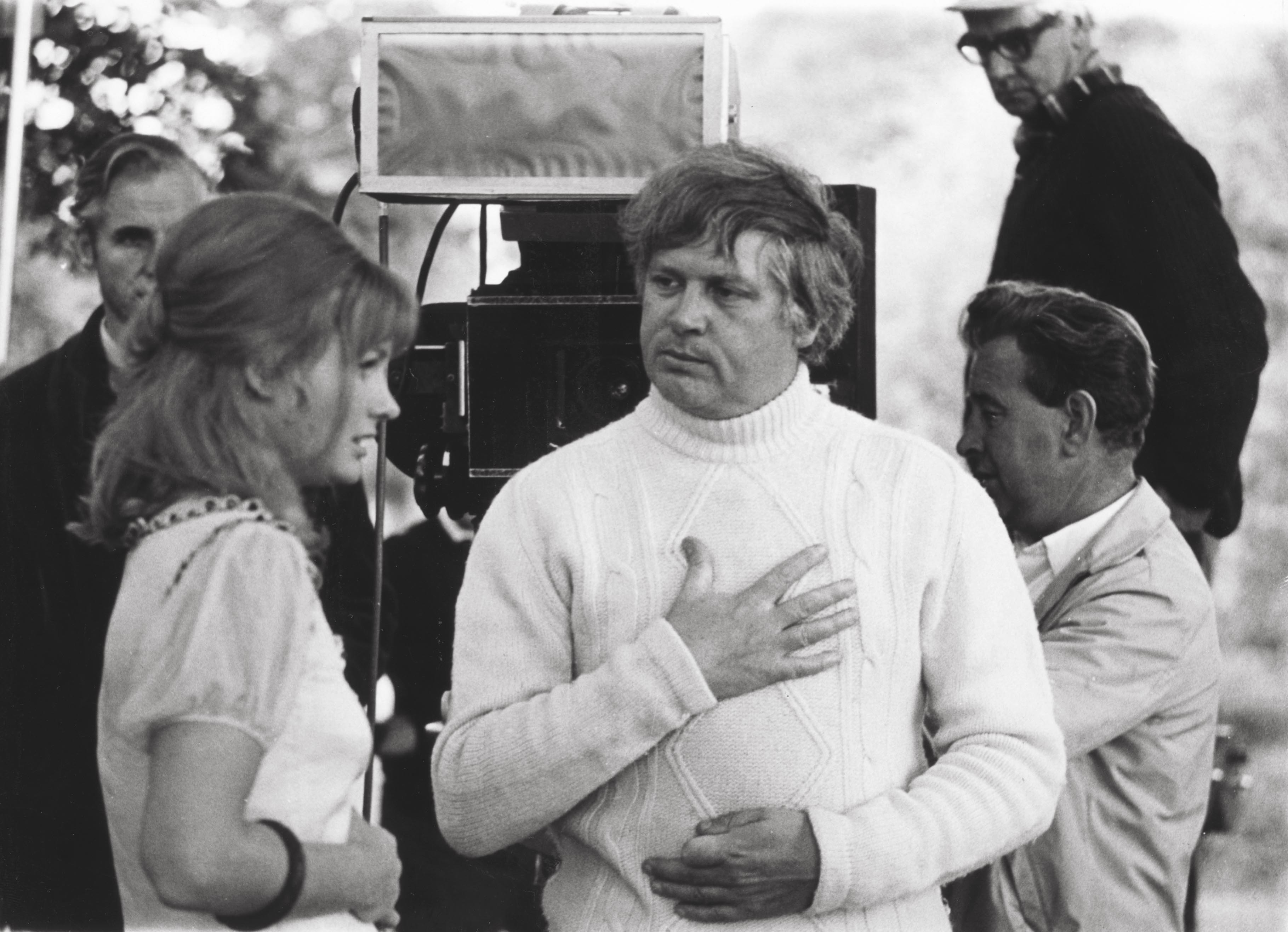

A newly restored version of the romantic drama that was issued with an X certificate in 1969 arrives at the BFI this week. Geoffrey Macnab looks back at a film that was as profound as it was provocative, by a maverick director who was never given his due...

It’s hard to tell what’s most subversive about Women in Love, Ken Russell’s landmark 1969 DH Lawrence adaptation. Was it the homoerotic naked wrestling? Or those many quieter moments when the characters talk so earnestly about love, sex and the meaning of life?

“You seem to be reaching for the void but then you realise you’re a void yourself,” the ruthless industrialist Gerald (Oliver Reed) muses, in an effort to explain his innermost angst to his lover Gudrun (Glenda Jackson). That’s not the kind of remark you’ll ever hear in any mainstream release this summer.

Women in Love, screening in a restored version at the BFI Southbank this week, remains famous for its full frontal male nudity: Reed and Alan Bates grappling in front of a blazing fire and then vowing undying friendship. Reed admitted in his autobiography that he and Bates had drunk a bottle of vodka each before filming the scene. Even with the alcohol fortifying him, the hell-raising actor still felt acutely self-conscious. The film’s cinematographer Billy Williams later told the BBC that after the two men stripped off, Reed “looked at Alan Bates and said, ‘He has got a bigger dong than me’”, before he “went into the corner to try to improve matters”.

It’s arguably the most celebrated scene in Russell’s entire film career and yet it was Reed who was responsible for it being filmed in the way it was. The original screenplay had a much tamer, more stylised set-up that would have shown the men wrestling by moonlight on a river bank. Reed convinced the director to film the scene in the raw, gladiatorial way that Lawrence wrote it.

The British Board of Film Classification was perturbed by shots where the men’s “genitals are clearly visible”. Russell argued forcefully that this was a pivotal scene and should remain intact. He darkened the images but the movie was given an X certificate – a badge of shame at the time, primarily reserved for porn and horror.

When Women in Love was released in the UK, it was promptly billed as “the year’s most controversial film”. “FOR ADULTS ONLY” was slapped on the posters in capital letters – as if this was one of those smutty Confessions of a Window Cleaner-style sex comedies that the British film industry was soon to churn out.

Despite the storm whipped up in the media, Women in Love was more respectfully received by critics than were most of its maverick director’s later movies. Russell was a flamboyant and often outrageous filmmaker. He started his career making a series of films about well-known composers for the BBC, helmed the Len Deighton adaptation Billion Dollar Brain (1967), directed the wildly over-the-top Tchaikovsky biopic The Music Lovers (1971), and went on to work with The Who on the rock opera Tommy (1975).

As Russell’s career progressed, his feuds with the British press intensified. After Evening Standard reviewer Alexander Walker attacked his historical epic about nuns and demonic possession, The Devils (1971), the infuriated filmmaker hit the critic on the head with a rolled-up newspaper on live TV. Walker, though, had admired Women in Love, calling it “exceptional … immensely complex but perfectly controlled”. He even argued that Russell’s movie was an upgrade on the original novel, avoiding “Lawrence’s overblown romanticism”.

“Passion is here in bucketfuls but it is expressed with such honesty of purpose that no rational person could be offended,” the Daily Express agreed.

This was indeed a surprisingly faithful adaptation of the 1920 novel. To capitalise on the film’s release, Penguin published 100,000 copies of a special film edition and reported that, thanks to Reed and Jackson, they were “selling like hot cakes”. Russell claimed that he had dispensed with large parts of the original screenplay by Larry Kramer and gone back to Lawrence’s original text. “Together we agreed that the screenplay should more closely reflect Lawrence’s work,” the director wrote in his 1991 autobiography Altered States.

Miranda Bowen directed a well-received 2011 BBC TV film of Women in Love, starring Rosamund Pike and Rachael Stirling. “Obviously, you can’t go very far down the DH Lawrence line without coming across Women in Love very quickly. It is such a seminal film… such a cornerstone that it’s impossible not to be influenced by it,” Bowen tells The Independent. “He really tried to look at how we can express sensual and sexual feelings between men and women in a very visceral way without it becoming pornographic.”

As she pursued her own adaptation, Bowen was struck by how successful Russell had been “in really understanding and trying to pursue a visual form of DH Lawrence’s writing”. She adds: “I was incredibly intimidated by that!”

The story is set in a Midlands mining town shortly after the end of the First World War. Two sisters, the artist and sculptor Gudrun (Jackson), recently back from London, and schoolteacher Ursula Brangwen (Jennie Linden), are chafing against their background – “the amorphous ugliness of a small colliery town” as Lawrence characterised it. They both end up having intense affairs with men in the town, Gudrun with the wealthy but tormented Gerald Crich and Ursula with the free-thinking school inspector Rupert Birkin (Bates), the character often said to have resembled Lawrence most closely.

It’s the kind of film that you could easily imagine Call Me by Your Name’s Luca Guadagnino making today, an intense and beautifully crafted period drama that looks honestly, and without prurience, at love, friendship and sexuality.

Jackson, who won an Oscar, gives a searing performance as the endlessly curious and adventurous Gudrun. In one famous scene, she is shown performing an improvised Isadora Duncan-like dance before a herd of surly Highland cattle. She is fascinated by Gerald’s strange mixture of arrogance and vulnerability, his cruelty and his tenderness. He’s an imperious character but seems defenceless next to her.

I do feel that ‘Women in Love’ hasn’t been honoured in the way it should have. Whether you like it or loathe it, it is undeniable that Russell was visionary

Russell regarded Jackson as a muse. He was fascinated by how her face could look “downright plain” one moment and “incredibly beautiful” the next. Pregnant when she played the role, she had a force of personality that startled even him.

Reed was similarly cowed by Jackson. “Put her in gear on screen and she is like a Bedford truck. She will run all over you,” he later commented. The fiery hard-drinking actor was exceptional as Gerald. In his more desperate moments towards the end of the film, he reminds you of Mark Ruffalo as the cocksure male reduced to a state of cowering sexual jealousy in Yorgos Lanthimos’s recent Oscar winner, Poor Things.

For her part, Jackson remained intensely loyal to Russell. Late in her life, after she had retired as an MP and resumed her acting career, she continued to complain about how little respect he had received from the British film industry. Russell, she said, was still being caricatured in the media as a “monster of depravity”, while she regarded him as a “marvellous, marvellous director”.

“I think the way this country has treated him is an absolute disgrace. It’s almost as though everybody on the production or direction side of cinema in this country simply don’t want to hear his name,” Jackson told the BBC’s This Cultural Life show in late 2022. “I think that he, at the peak of his talents, made fundamental changes to British cinema and I think it is scandalous he has been discarded.”

Jackson is right. Russell’s movies aren’t very often revived. Women in Love may be sold out at its BFI Southbank screening this week, but even this film, acknowledged as one of his masterpieces, isn’t easy to find on streaming services.

“I do feel that Women in Love hasn’t been honoured in the way it should have,” Bowen tells me. “Whether you like it or loathe it, it is undeniable that he [Russell] was visionary. To get performances like that out of the actors, particularly when you’re doing something quite informal with the camera work, is really astonishing.

“I wonder if the British weren’t a bit intimidated… there are many European and American filmmakers who’ve pushed cinema in the way Ken Russell tried to – and yet he was humiliated and shunned as though his films were some moral debasement of cinema. That’s a massive misinterpretation of what he was trying to do.”

Fifty-five years after its first release, it’s easy to forget how groundbreaking Russell’s movie once appeared. It evokes the post-First World War era poignantly (we continually see old soldiers milling around the streets next to the mine workers); deals perceptively with class and industrial strife; and yet also stands as a quintessential 1960s movie.

Elements of the film may grate with modern sensibilities – moments of chauvinism and a tendency to foreground the two men’s experiences at the expense of those of the sisters. But Women in Love, like its mercurial director, is positively ripe for rediscovery.

‘Women in Love’ screens at BFI Southbank on Friday 26 April at 2.40pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments