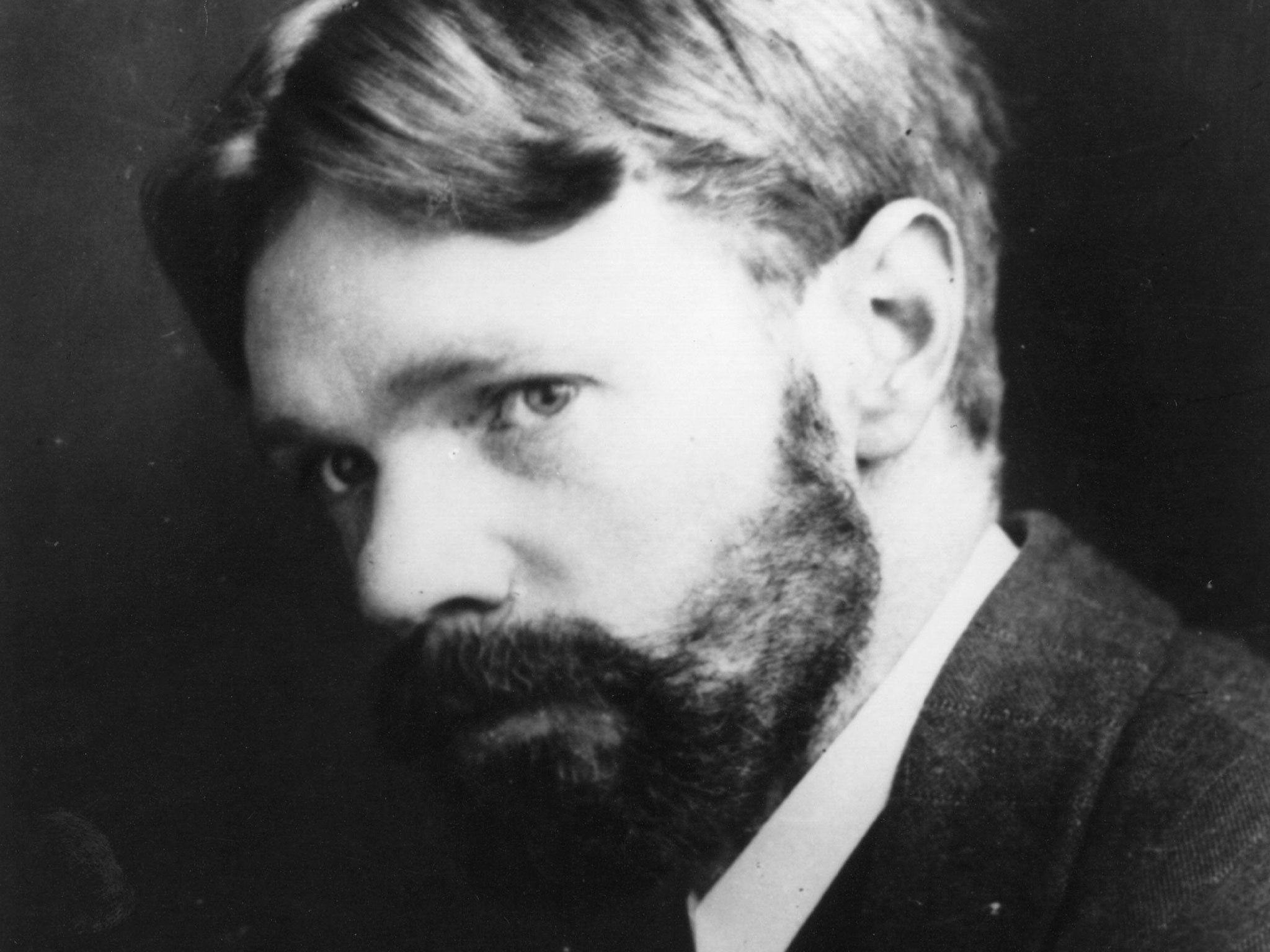

The Rainbow by D H Lawrence, book of a lifetime: Eccentric and dangerous

When Tessa Hadley was young she didn't just love D H Lawrence's novels - she used them as religious texts, to teach her how to live

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a lifetime of reading, there are so many important books. We never know when to expect the next significant encounter: picking up a new book, crossing the threshold into its story or its argument, its elegance or its intelligence. But there is a special place reserved in our memories for the favourites of our youth. When you're very young, you're not only opening yourself to the different world of the book, you also want the book to enter your own world and your life, to change everything. When I was young I didn't just love D H Lawrence's novels – as I still do now, but differently – I used them as religious texts, to teach me how to live.

I loved The Rainbow most: a story of several generations of one family in the Nottinghamshire countryside. It's hard to re-read it now, not because I don't still think it's a fantastic book, but because I know it too well. So many of its sentences, with their exalted, sensuous language – in the “starry multiplicity of the night” Tom Brangwen knew “he did not belong to himself” – are worn so smooth with my own handling, like a rosary, that I can hardly take in any longer what they say.

Certain scenes are as important as foundation myths in my imagination: Tom's first sighting of Lydia, her pressing back against a bank as he passes in his cart; Tom's drowning at night in the flood. I still think about Will and Anna's argument in Lincoln, every time I'm inside a cathedral: his swooning response to the soaring gothic architecture, her wanting to get out in the fresh air. When I had small children I remembered how Will loved his little daughter Ursula too intensely, pressuring her and making her unhappy when they planted potatoes together.

I'm not sorry that I used The Rainbow as my guide to life. The discipleship had its eccentric and dangerous and comical aspects. It put me off higher education; I went to university but I never forgot Ursula seeing through the college as a “sham workshop”, “flunkey to the god of material success”. It gave me some strange ideas about men and women, which needed a little working through. But how could I regret being influenced by the grandeur of the novel, the ambition and seriousness of its vision and its politics? I had my own intimations that family life was full of grandeur, if only we could find a language for it.

Tessa Hadley's new novel is 'The Past' (Jonathan Cape)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments