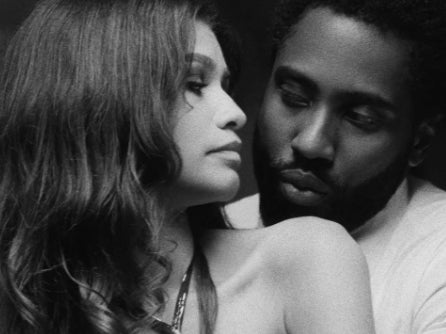

Why is Sam Levinson’s Malcolm & Marie proving so controversial?

The Netflix film shot in quarantine by the Euphoria creator with Zendaya and John David Washington has been heavily criticised by some. Micha Frazer-Carroll looks closely at what it got so wrong

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s hard to predict how people will respond to movies about dysfunctional couples having screaming matches for over an hour. Marriage Story? Critics loved it, and the movie was nominated for Best Picture, among other Oscars. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Another Best Picture nomination, and an instant classic. Euphoria director Sam Levinson’s newest release, Malcolm & Marie? Not so much.

The drama, which joins the ranks of other movies made in the pandemic like Zoom-horror Host, apocalyptic virus-thriller Songbird and romantic heist movie Locked Down, has a simple enough premise: Malcolm (John David Washington) is an up-and-coming director who has just released a new film, and his girlfriend Marie (Zendaya) is a recovering addict, whose life provides much of the source material for Malcolm’s movie. We join the pair on opening night, after which Malcolm forgot to thank Marie in his introductory speech. All hell breaks loose. We proceed to follow the two around Malcolm’s (lovely) estate in the Hollywood Hills, where they viciously fight and make up, discussing their relationship, the film, and the industry itself, over the course of an hour and 40 minutes.

Some critics liked it – with The Independent awarding it four stars. But many hated it. The headlines contained a surprising level of vitriol: Vulture described its “utter emotional inauthenticity”; Buzzfeed reported “Zendaya’s new movie isn’t good”; meanwhile, GQ simply asked, “What’s the point of Malcolm & Marie?” I had a lot of mixed feelings about the film. Both actors do an incredible amount of heavy lifting in a production that is so stripped back: it has no other cast members, a tiny crew, was written in only six days and shot in two weeks under rigid pandemic restrictions, takes place in only one location, spans the course of one evening, and to top it all off, is shot in black and white. But much of the script is exhausting, repetitive, unnecessarily conceptual, and intentionally riles anyone who dares criticise it.

It is unsurprising that this film didn’t play well with critics – considering much of the dialogue is spent directly attacking them. Throughout the film, Malcolm delivers long, winding monologues where he lambasts entertainment writers, repeatedly referencing the stupidity of a particular “white lady from the Los Angeles Times” who gave his last film a scathing review. Reviewers didn’t respond well to this apparent fourth wall-break, particularly as this fictional white lady critic seems like a reference to Katie Walsh, a real-life LA Times writer, who did indeed give Levinson’s last movie, Assassination Nation, a bad review.

While Levinson has the right to criticise critics, he almost goes so far as to suggest that they are wrong to do their jobs – and by implication, wrong to say anything bad about his movie. Marie pushes back gently: “So what, Malcolm, you wanna make movies and no one’s allowed to say anything bad about them?”, but it’s Malcolm’s stance that comes out on top. Finally, its execution is also literal and lazy: watching Malcolm serve as a mouthpiece for Levinson’s industry gripes, I felt like I was being subjected to an angry, moralising rant, rather than a good-faith artistic exploration of a topic.

Race only complicates this problem. Levinson is white (and, notably, the son of Hollywood legend Barry Levinson, who directed the box-office success Rain Man). Yet, there are many moments where it feels as if Malcolm, who is a Black Hollywood director, serves as a mouthpiece for Levinson’s own opinions on race and filmmaking – making them harder to disagree with. The points made about reviewers are far from anti-racist or even progressive (at one point in his tirade, he derides them as “woke”) – but because they’re coming out of Malcolm’s mouth, we’re tempted to believe they are grounded in his experiences as a Black man. As Robert Daniels pointed out in The Guardian, this also applies to the continual scolding of the LA Times white lady critic: “If Malcolm were a white man … he would possess far less leeway to flog a female journalist to this degree. But through the mouth of a Black man like Malcolm … such lines of attack are fair game. Even when they are in fact ambushes.”

Levinson continues to employ this ventriloquism to pre-emptively justify his right, as a white director, to make films about the experiences of Black Americans. Malcolm runs back and forth from the house to the garden, screaming into the night. “The fact that Barry Jenkins isn’t gay, is that what made Moonlight so universal?” It seems the implication is that if Barry Jenkins, a straight Black man can do that, Levinson, a straight white man can do this. “F*** you for inhibiting the ability for artists to dream about what life may be like for other f***ing people,” Malcolm shouts at his invisible critics, followed by a string of other expletives. It gets more intense: he describes the idea that Black people are best placed to make Black films as “purist, moralistic, academic nonsense”, and wishes carpal tunnel syndrome on the white LA Times lady who disagrees with him.

We do not know for sure that these are the real-life opinions of Levinson – he pointed out this is simply an “assumption” in The Independent last week. But given what we know about the experiences of Black people in the industry, it’s also hard to believe they are Malcolm’s. Coming away from the movie, I longed to ask Levinson: if that eight-minute soliloquy isn’t how you really feel, then what on earth was it all about.

In all this, you might also be wondering: isn’t this film supposed to be an intimate look at the ins and outs of a tumultuous relationship? Why have we found ourselves knee-deep in a monologue about the connection between the art and the artist, and the strengths and pitfalls of cultural criticism? This question perhaps points to the most annoying thing about the film: its passion is in the wrong place. Monologue is a chance for the truth to punch through – to send an electric current through the hearts of your audience who, ultimately, want to feel something. It can also be a compelling vehicle to interrogate life’s biggest problems (take Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? or Marriage Story, and their shared focus on the anguish of a failing marriage) – but Levinson’s subject matter isn’t universal, urgent or meaningful enough for it to work.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

RELATED: The 43 best original films to watch on Netflix, ranked

Levinson could have homed in on the aspects of Malcolm & Marie’s relationship that many of us can relate to: the power imbalance brought about by their age gap and class difference, the complexities of mental health and dating, or the exhaustion of not knowing how to leave a toxic relationship. But instead, he spends much of the film oscillating between lamenting how hard it is to be a Hollywood film director, and engaging in petty industry infighting that doesn’t interest most viewers outside of the LA bubble. These feel like issues better hashed out directly with critics or on the therapists’ couch, not via a 100-minute Netflix movie that everyone is being asked to watch.

Not all of those 100 minutes are bad – in fact, based on its reviews, I had expected it to be far worse. Visually, it is gorgeous: Euphoria’s Marcell Rév creates striking cinematography on black and white film, and Zendaya wears a beautiful, glittering gown by designer Law Roach, who has been her stylist since she was 14. Both Zendaya and Washington put in the work to make the shallow premise of Malcolm and Marie’s relationship believable, expertly cycling through fiery rage and intimate passion. There are moments, particularly when the film shifts to the smaller issues between the pair, that are genuinely moving. Meanwhile, Levinson’s assertions are not all wrong – some of his points about authorship genuinely intrigued me (for example, must all work made by Black people be political?) before he starts going in too hard.

In light of Doug Liman’s Locked Down and Adam Mason's Songbird (both badly reviewed), it’s worth considering that history will extend a certain level of forgiveness to these experimental pandemic movies. After all, Malcolm & Marie took a risk – which is what Malcolm believes filmmaking is all about. But in the meantime, Levinson’s punishment is having to give suitably diplomatic answers to questions about whether he hates all critics for the entirety of his press tour. As for the white lady from the LA Times, he said: “Look – it just sounded funny.”