We need to talk about the emotional abuse in Malcolm & Marie

As critics are split on the new Netflix film, Olivia Petter examines its troubling depiction of abuse and how it can go unnoticed in relationships

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

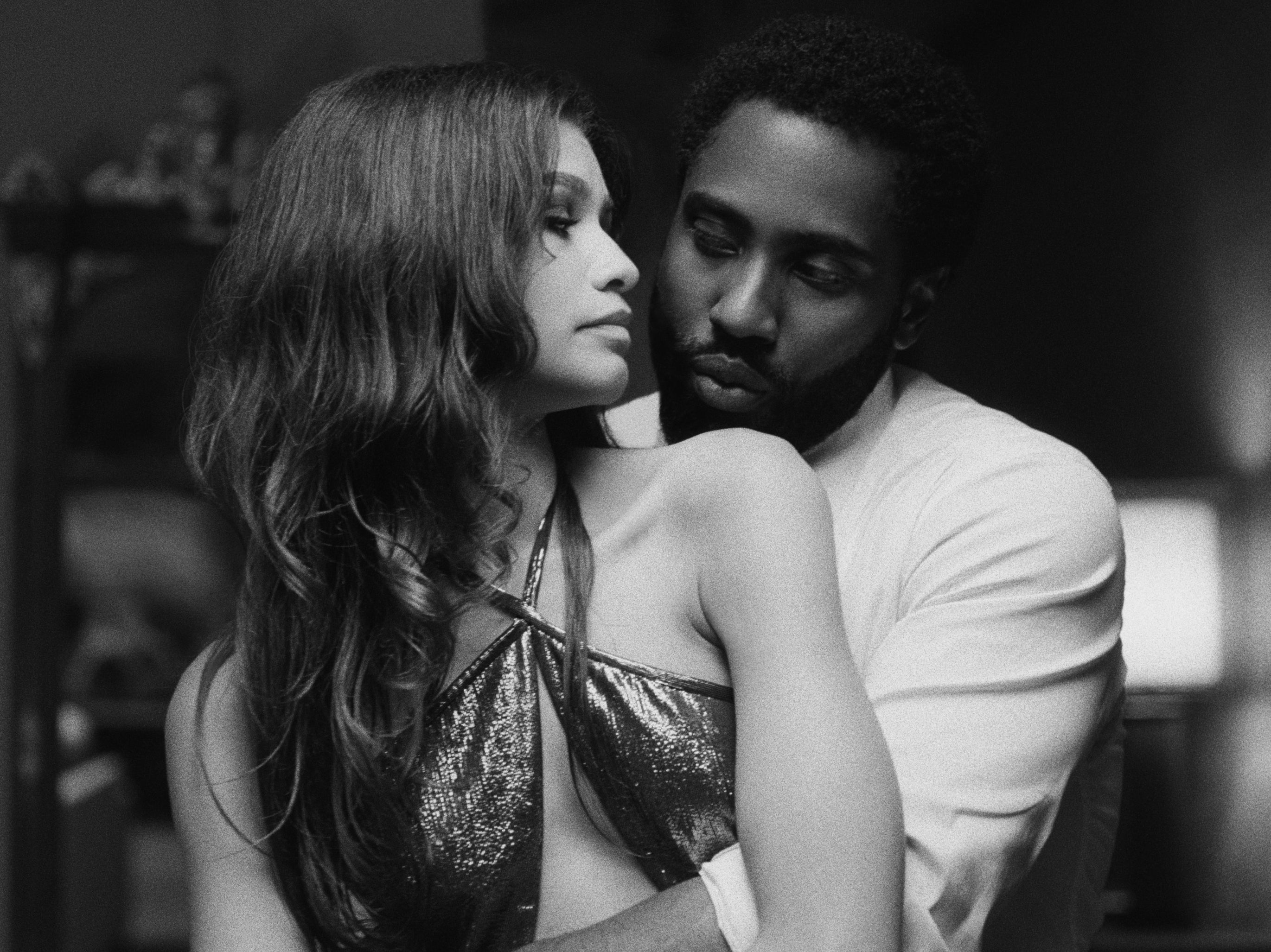

Your support makes all the difference.Fifteen minutes into Malcolm & Marie, Sam Levinson’s black-and-white Netflix film about a conceited filmmaker and his partner, we hear the word “abuse”. Malcolm (John David Washington) is sitting at the kitchen table eating mac and cheese, verbally tearing into his girlfriend Marie (Zendaya) in between mouthfuls.

“You're mentally unstable,“ he screams. “F***ing delusional!” Goaded by her boyfriend of five years, Marie soon emerges on the other side of the room: “Are you actually yelling and belittling me from across this house because you are too busy eating mac and cheese?” she retorts. “Do you know how disturbing it is that you can compartmentalise to such a degree that you can abuse me while eating mac and cheese?” This gets Malcolm’s attention. “Abuse you?” he scoffs. “Verbally abuse me.” Marie replies, prompting Malcolm to thank her for the “important clarification” before telling her to “get the f*** outta here”.

This is just one of the many troubling incidents in the film. The story stems from a singular argument over Malcolm’s failure to thank Marie in his speech at the premiere of his film earlier in the evening. A film that, Marie argues, is based on her history with depression, addiction and eventual recovery to sobriety. But as the film unfolds, it becomes clear that the cracks in their relationship run deep. Theirs is a romance complicated by power imbalances, age differences, and the seductive toxicity of a push-pull dynamic that keeps them in a perpetual state of being both enthralled and enraged by one another.

Critics have rebuked the film’s self-importance, with some even calling it pretentious. But what is most concerning is the way that Malcolm & Marie has been presented. Not as a film about an emotionally abusive relationship, but as a love story. The description on Netflix, for example, references a “tumultuous night [that] will test the limits of their love”, while promotional material carries the tagline “madly in love”. Even Levinson himself has admitted that he doesn’t even know if this relationship is healthy or toxic, a question he explicitly puts to the viewer at the end of the film by playing Outkast’s “Liberation”, which carries the refrain “there’s a fine line between love and hate“.

But viewers are not quite as ambivalent, with many advising survivors of abuse to think twice before watching it. “I tuned into this film in support of Zendaya and because it was marketed as a film about love, in my opinion it is absolutely not about love in any capacity,” tweeted one person. Another added: “It is interesting that they marketed it as a love story when it is the very opposite. It is a story of emotional and mental abuse within a romantic relationship.“ Others focused on the specificities of Malcolm’s behaviour. “The way he was yelling at her, insulting her, and gaslighting her did not sit right with me at all and made me really anxious,” noted one viewer. Another added: “Malcolm and Marie was just a movie chronicling emotional abuse, you can’t convince me otherwise.”

Refuge, the UK’s national charity for supporting domestic abuse survivors, states that there are various types of behaviour that could be considered psychological abuse. These include name-calling, threats, manipulation, gaslighting, and being charming immediately after being abusive. But, as the charity Relate indicates, this type of abuse is often thought of as a “grey area“. Indeed, it was only last year that the government passed a bill that would see psychological abuse legally recognised as a crime as part of the Domestic Abuse Bill 2019-21. The bill emphasises that domestic abuse “is not just physical violence, but can also be emotional, coercive or controlling, and economic abuse”, the government website states.

We see a lot of the aforementioned behaviour in Malcolm & Marie. Throughout the film, the two protagonists dissect and dismantle one another’s characters with cruel precision as if it were a competition to see who can cause the most emotional pain. She criticises his ego, calls him “mediocre”, and manipulates him into thinking she’s still using drugs, even going as far as sleeping with his friends in order to prove a point. But it is Malcolm whose words sting the most.

He calls her “jealous” when she tries to explain how hurt she was that Malcolm didn’t cast her, a former actor, in his film, exploits her history with addiction to belittle her (“that’s what makes you so f***ing unique, right?”), and throws her suicide attempt in her face. Malcolm raises the differences between physical and verbal abuse in an attempt to suggest the latter is less problematic. If anything, this film is an exercise in illustrating why that is not the case.

Like in many toxic relationships, for Malcolm and Marie, their sex life is not dampened by their dysfunction, but fuelled by it. One moment they’re screaming in one another’s faces and the next, they’re smothering each other in kisses with the same degree of passion. But even when the sounds the characters make are those of pleasure rather than pain, they’re not doing any less damage to one another, notes senior therapist Sally Baker. “In emotionally abusive relationships, sex can become purely transactional,“ she says, noting how, in one scene, Marie looks as if she is going to perform oral sex on Malcolm so he calms down before raising another issue she had with his film.

“The scenes where they’re all over each other are no different from their argument scenes,” Baker adds. “Both are characterised by fury, revenge, and adrenalin.” Malcolm highlights this dichotomy himself towards the end of the film, when he tells Marie that he goes from wanting to “cut [her] head off“ one minute to wanting to “kiss [her] beautiful stupid little face the next”. Moments later, he asks Marie if they should get married, because he feels like they’re going to get married and divorced “at least” a couple of times so they may as well get started. They start kissing, and then it’s back to arguing again.

All this, Baker argues, shows how normalised abusive relationships have become for so many people. “It was ugly and triggering to watch the way their dynamic is presented,“ she adds. This is also reiterated at the end of the film, when Malcolm wakes up the next morning to find Marie standing alone outside their property. He stands beside her in silence, leaving the viewer with an uneasy feeling that a repeat of the previous evening is not far away for this couple. And as long as they are together, it never will be.

You can contact the 24-hour National Domestic Violence Helpline by calling 0808 2000 247.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments