Face/Off: How Nicolas Cage, Die Hard and a confused Johnny Depp helped make an action classic

No film has been sillier, bloodier or Nic Cage-ier than John Woo’s 1997 classic. As the movie closes in on its 25th anniversary – and is parodied in Cage’s gonzo satire ‘The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent’ – Tom Fordy explores its wild production and the strange reason Johnny Depp turned it down

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

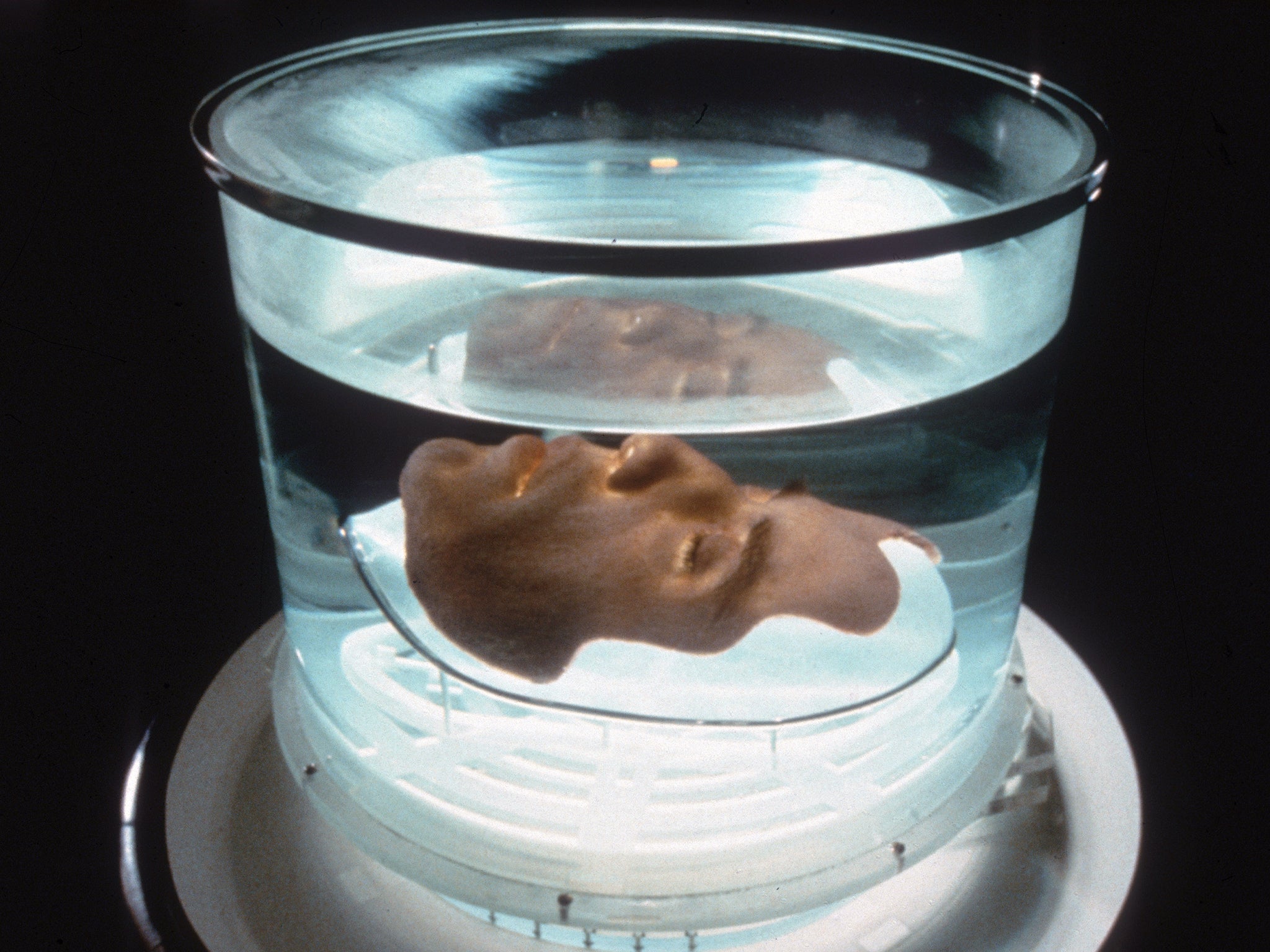

Your support makes all the difference.Nicolas Cage had come face-to-face with his own image. He was disturbed. It wasn’t the sight of John Travolta with Cage’s own face grafted on – as happens when the actors trade places in the 1997 actioner Face/Off – but when Cage met a life-size replica of himself. It had hair, wrinkles, remote controlled facial features, and an internal bladder system that allowed the Cage-a-like dummy to simulate breathing. He and Travolta had been recreated as robotised dummies for the film’s pivotal surgery scene, in which their faces are sliced off and swapped around.

“Nic apparently saw the replica and was really affected,” says Michael Colleary, co-writer and producer of Face/Off. “They had to go in and clear the set or something, so Nic could go in and look at it… it looked like him dead!” “He was flipped out!” laughs Mike Werb, Colleary’s writing and producing partner.

Cage meets a similar, Madame Tussauds-style replica in the new self-lampooning action-comedy The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent (“Is this supposed to be me? It’s grotesque”), which is released in cinemas on Friday (22 April). It’s a nod to Face/Off’s rightful rep as one of the Nic Cagiest things to happen in the whole history of bonkers, mad-eyed, cranked-up Cage-ness. Now, 25 years since its original release, Face/Off remains part of the Holy Trinity of Nic Cage Nineties action, along with The Rock (1996) and Con Air (1997). It came just a year after Cage had won the Academy Award for Leaving Las Vegas, and his crushing performance as a suicidal drunk. Travolta, meanwhile, was riding the wave of resurgence after the cutting-edge cool of Pulp Fiction (1994) and Get Shorty (1995). Travolta had even been branded, amusingly in hindsight, “the coolest man alive” by Empire magazine in April 1996.

In Face/Off, Cage and Travolta play mortal enemies: Cage is the cassock-wearing, backside-squeezing terrorist-for-hire Castor Troy (“I’m Castor Troy! WOOOO!”); Travolta is wounded, sourpuss FBI agent Sean Archer, whose son was killed by Troy years earlier in a botched assassination. A high-octane shootout between them puts Troy in a coma, forcing Archer to locate and deactivate the baddie’s final bomb. But how? By having a face transplant and masquerading as Troy in a top-secret prison, where Archer can surreptitiously squeeze information from Troy’s incarcerated brother. Meanwhile, the real Castor Troy awakes from his coma, discovers his face is missing, and has Archer’s face transplanted onto himself – it was going spare, after all – thus taking Archer’s place as a top federal agent and flawed family man.

So ludicrous is the concept of Face/Off that when Colleary and Werb pitched it to their agent, they were laughed out of the office. “But once we hit on the idea, we couldn’t stop writing,” Werb says. Conceived in 1990, Face/Off came on the bare, bloodied heels of Die Hard. “The order of the day was, ‘Where’s the next Die Hard? Show me the next Die Hard!’” says Colleary, who – along with Werb – was trying to get a foothold in the film business.

Hollywood was spending big bucks on original spec scripts, and adrenalised, high-concept ideas were starting to muscle out the Schwarzenegger and Stallone-type action that had reigned over the Eighties. The likes of Speed and The Rock – along with other Die Hard variants – soon supplanted the pneumatic, oily-biceped power of Commando and Rambo. “We got together and said, ‘What would our Die Hard be?’” recalls Colleary.

“We were astounded by how bad some of these action films were,” says Werb. “The bad guy was always nude in a hotel, doing one-armed push ups and plotting to take over the world.” See Die Hard 2 – big on nude workouts and devious plotting. “One of the things we thought was, ‘Why can’t the bad guy be as interesting as the good guy?’ Which eventually morphed into, ‘Why can’t the bad guy be the good guy?’”

Face/Off began as Die Hard in a prison, partly inspired by the 1971 Attica Prison riot and partly inspired by the gangster classic White Heat, in which a federal agent goes undercover in a jailhouse to question James Cagney’s on-top-of-the-world criminal. “We were working under the idea that our hero goes undercover as somebody else,” says Colleary. “Then it became, somebody on the outside takes over his life. But how does that work? We really backed into the idea of a facial swap.”

The story was originally set 100 years into the future – an easy means of explaining away the face-swap surgery – and opened with a set-piece in an organ bank, which was like a regular bank. “You could get anything you wanted there if you had enough money,” says Werb. One futuristic aspect remains in the final movie: a hi-tech prison where inmates are controlled by giant magnetic boots.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Powerhouse producer Joel Silver picked up the script for Warner Bros, but there were creative clashes between the writers and the studio. Warner Bros opted to make Demolition Man instead – a set-in-the-future (but horribly aged) smackdown between Sly Stallone and Wesley Snipes. “We never had any support at Warner Bros,” says Colleary. “They already had Demolition Man in the pipe and they looked at it as the same thing – futuristic action, mano-a-mano, what’s the difference?” Thanks to a small print oversight, Colleary and Werb got the rights back. “The day after, three different studios called to try and get the script,” says Werb.

After Paramount Pictures jumped on board, a further turning point came when Steven Reuther and actor Michael Douglas came onboard as producers. Douglas had read every script draft and told the writers: “This is a psychological thriller masquerading as an action film. Write that movie and you’ll get not just movie stars but great actors.” Douglas explained that Face/Off presented a unique challenge for actors. “If we get offered good and evil, it’s always as identical twins,” Douglas said, speaking as an actor. “This is something different.”

Colleary and Werb had originally written their movie with Schwarzenegger and Stallone in mind – Hollywood’s biggest, most pumped-up action stars. They could play with the stars’ well-known personas, such as Stallone saying “I’ll be back” with a giant-elbowed nudge and a wink. Other twosomes were also discussed. “Bruce Willis and Alec Baldwin! Mick Jagger and David Bowie!” says Colleary. “When Michael Douglas came on to produce, we said to him, ‘Why don’t you do it with Harrison Ford?!’”

John said something like, ‘Any chance of you gaining any weight before we shoot this movie?’ Nic said, ‘No, I don’t think so.’

Paramount, though, wanted Johnny Depp, who would have potentially played opposite Cage. Douglas even went to the set of the Depp-starring action-thriller Nick of Time and tried to talk Depp into it. The actor apparently read the Face/Off script, but lost interest when he realised that it wasn’t about, erm, hockey. Cage, meanwhile, was shooting Die Hard-on-a-plane movie Con Air at the time (Cage has called Face/Off and Con Air – released in the same year – his “double album”). Once Cage and Travolta were cast, they all met at Reuther’s house. “They were throwing a small dinner party – we were meeting with Nic and John for the first time,” says Werb. “Travolta was there first. He was very nice, chatty, and gracious. Then in the middle of us talking to John, he froze and looked past us like we weren’t there. Nic Cage had shown up. The two of them started bonding and talking about each other’s more famous on-screen quirks – ‘In this movie you did that… in another movie you did that.’ Michael and I almost simultaneously receded behind this palm tree and shook hands. We said, ‘You know what, this movie’s actually going to work!’”

Cage and Travolta studied each other intently. Travolta, says Colleary, is a natural mimic and would impersonate other stars – Jimmy Cagney, Edward G Robinson, Barbra Streisand. Cage and Travolta, though, were in relatively few scenes together, so looked at the dailies to get a measure of each other. Cage was only willing to impersonate Travolta so far. Colleary and Werb recall queuing up at a buffet-style platter with both stars before filming began. Travolta piled his plate with carbs and lamb chops, and looked back at Cage, who had a modest helping of kale and salad. “John said something like, ‘Any chance of you gaining any weight before we shoot this movie?’” laughs Werb. “Nic said, ‘No, I don’t think so. I’m shooting Con Air – I’ve been in prison for years!’ John said, ‘It’s not your problem, it’s mine!’” “He started putting lamb chops back on the platter,” laughs Colleary.

Regarding his appearance, Travolta had reservations about one gag, when Troy laments his new Travoltan looks: “This nose, this hair, this ridiculous chin!” He summoned the writers and probed them about the joke – to be sure they weren’t just making fun of him. They told him: “John, you are famously one of the most handsome people on Earth. But right now, you are Nic Cage! And Nic Cage as Castor Troy is a total narcissist – nobody is better-looking than he is!”

Face/Off was always more than a two-man show. Just as crucial was director John Woo. By the mid-Nineties, Woo was already a legend of Hong Kong action cinema: innovator and master of slow-motion shoot-outs, guns-in-faces standoffs, long sweeping trench coats, and double pistols thrust forward, bullets pumping. Colleary and Werb first met Woo while he was editing Broken Arrow – another mano-a-mano actioner with Travolta (this time vs Christian Slater). “Face/Off is the best action script I’ve ever read!” Woo told them – his very first words to the writers.

Other directors had been attached to Face/Off, each wanting to take the concept in their own direction, but Woo understood something the others seemingly didn’t: that Face/Off was fundamentally about characters, not action. According to Colleary and Werb, all Woo wanted to talk about was character. He kept the writers close at all times during production, and added his own character details: Archer’s hand-down-the-face gesture of love; Troy tying the laces of his childlike bomb-maker brother, Pollux (Alessandro Nivola – most recently seen in The Many Saints of Newark).

The personal stakes emerge from a deliberate spin on the action genre: Troy’s ticking time bomb is disarmed nonchalantly; the real threat is Troy’s grip over Archer’s family. The organising principle of the story, say Colleary and Werb, was that these mortal enemies became “better people in each other’s lives than they were in their own”. See Troy, in the guise of Archer, being a more attentive husband to Archer’s neglected wife (Joan Allen) and an unlikely mentor to Archer’s rebellious daughter (Dominique Swain). See Archer, in the guise of Troy, becoming a father to Troy’s abandoned five-year-old son. Face/Off is more than skin deep.

Still, for all the character nuance – balanced out with Cage’s devilish mania – Face/Off was prime action fodder for Woo, a director who likes to turn up the action as he shoots; to throw big explosions against the wall and see what sticks. Beginning with a chase down a runway – Travolta in a helicopter, Cage in a plane – the film is a masterclass in off-the-scale, escalating action: an epic shootout to the sound of The Wizard of Oz’s signature ballad “Over the Rainbow” (“I’m so glad they left it in,” Woo once said about the tune, “because it gave the killing scene so much meaning”); a memorial service than turns into a speedboat chase. Indeed, why settle a personal grudge with a gentlemanly chat or a simple punch-up when you can stick two stuntmen in a speedboat and chuck them 25ft in the air? (“That gets me every time,” Colleary says about the stunt.)

Those signature Woo flourishes – the slow-mo, the standoffs, the double pistols – become an exercise in duality: Cage and Travolta are mirror images of each other, extensions of the same entity, circling themselves in a deadly dance, guns poised, evenly matched, oddly in tune. In the film’s defining visual, Cage and Travolta stand either side of a two-sided mirror, facing themselves in the ultimate, self-reflective showdown. “[Woo] was very proud of it,” says Colleary about the shot. “I was on the set when he blocked it and had two guys standing back-to-back. I said, ‘Yeah, that looks cool…’ It wasn’t until I saw it that I thought, ‘That’s the movie! That’s the poster, That’s everything!’”

Just as Michael Douglas had told the writers back in their first meeting, Face/Off was a unique acting challenge: not just playing hero and villain, but playing one masquerading as the other; to both mimic and add layers to a character already established by another actor. Travolta’s version of Castor Troy becomes more sinister: quietly calculating, like a man with a purpose beyond chaos – he wants to become an “American hero” and corrupt Archer’s family. Travolta also finds a smidgen of remorse in Troy when he’s forced to visit the graveside of Archer’s dead son – the boy Troy killed years earlier – and faces the grief.

Cage as Archer, conversely, teeters on the edge. Passing himself off as a highly dangerous sociopath, he almost loses himself in the violence, while also trying to keep his inherent good and emotional turmoil buried. “In a way, Nic had a tougher acting job,” says Mike Werb. “When Nic was Sean Archer, he had to act like he’s Castor Troy but the humanity of Sean Archer has to bleed through at all times.”

Beyond the surgery itself (“We simply connect the muscles, tear ducts, and nerve endings,” explains the surgeon) the film is a series of bold-faced implausibilities: that Archer’s face transplant happens “off the books”; that Castor Troy, freshly awoken from his coma and faceless, still manages to smokes a ciggie without any lips; that Archer’s wife doesn’t spot that her husband has completely different hands (or, ahem, other bits); that Troy, posing as Archer, is named Time magazine’s ‘Man of the Year’ in a matter of days; and that Archer – after finally killing the bad guy – still gets his old face back, even though the surgeon who pioneered the procedure was burned alive in the first act. The writers laugh that one off. “We cover that with one weak line of dialogue!” says Werb. Indeed, the Feds are “bringing in their top surgical team”, we’re told, rather reassuringly.

Perhaps most implausible is that, in the end, Archer brings home Troy’s son as a substitute for his own murdered child – a mental breakdown waiting to happen. The implausibilities, though, are undoubtedly the fun of Face/Off. Released on 27 June 1997, Face/Off was a box office hit – making $245m (£187m) from a budget of $80m – and a critical success. Colleary and Werb were recently invited to introduce a screening at Quentin Tarantino’s arthouse cinema in West Hollywood. “We thought there would be 15 people and it was a packed house,” says Werb. “We were shocked.” A sequel is also in the works, with director Adam Wingard attached. Werb pays homage in his own way: he has Travolta’s cut-off face framed on his wall at home. What would Nicolas Cage say about that?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments