‘They were sort of profoundly beautiful’: Gus Van Sant on 30 years of My Own Private Idaho

A foundational text for the sad and queer, ‘My Own Private Idaho’ made arthouse stars of River Phoenix and Keanu Reeves. Thirty years after its UK release, Adam White speaks to the film’s writer and director Gus Van Sant about its production, its two leading men, and why it still matters all these decades later

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The road had taken River Phoenix far. Born in Oregon and raised in Caracas, he’d busked on LA street corners, fallen in love in the jungles of Belize, and in the summer of 1992 had wound up in Japan, among neon lights and superfans.

Gus Van Sant’s counterculture classic My Own Private Idaho had hit Asia. Phoenix was young, cool and beautiful, and the streets of Osaka, Tokyo and Kyoto teemed with screaming teenagers eager to glimpse their idol in the flesh. “They were just chasing him around,” Van Sant tells me. “In Japan, he was the model for a certain kind of look that was really popular in manga and cartoons at the time.” It’s partly why he had cast Phoenix in Idaho, as well as his good friend Keanu Reeves. “They were just so visible and at the top of their fame. Yet here they were playing in this more experimental piece – a gay piece.”

Thirty years after its release – it reached UK cinemas on 27 March 1992 – My Own Private Idaho is a foundational text for the sad and queer. Isolation, longing and unrequited love form its scaffolding; Phoenix’s street hustler Mike is its fragile nexus. He yearns for the mother who abandoned him. He tussles with a sexuality that grants him power and allure, yet a degree of vulnerability. He blocks his ears while the boy he dreams about makes love to his girlfriend in the next room.

When Phoenix died in October 1993 at the age of 23 – of a drug overdose outside a Los Angeles nightclub – his work in the film grew wings. Overnight, Phoenix’s performance was transformed into an unforeseen epilogue, his Rebel Without a Cause, his Dark Knight, or a young actor’s last, cruel hurrah. Phoenix made three more films in the wake of My Own Private Idaho, but nothing with as much of an emotional undertow.

We first meet Mike in his dreams. He’s on a long dirt road under a lilac sky, in a stranger’s stained overalls and a fur-lined coat. He speaks in riddles, cracks his neck, and faints; he’s a narcoleptic. We see a vision of his mother cradling him in her arms, before a smash cut to Mike in concentrated, practiced bliss. He’s receiving a blow job from a slob for cash, and a farmhouse falls from the clouds at his moment of climax. It’s an early sign of things to come: sexy yet grotesque, glamorous yet grubby, a burgeoning Hollywood star stuffed into an art film.

The streets, and the adolescent drifters who called them home, had always appealed to Van Sant. His first two films, 1985’s Mala Noche and 1989’s Drugstore Cowboy, were tales of broken homes and chosen families, about youngsters torn between lust and hopelessness.

“A lot of my work revolves around these ad hoc families made out of a kind of serendipity but also need,” the 69-year-old explains down the phone from Los Angeles. He’s not sure if it’s an inherently queer narrative, though, believing that every person – regardless of their sexuality – will at one point have found themselves on a similar quest. “I think it speaks to just being in the world – it’s just existence, and going where the world takes you.”

Van Sant himself had moved around a lot. As a child, each new city brought new challenges but also new opportunities for connection. He is most associated with Portland, Oregon – where many of his films, including Idaho, are set – but he’s also spent years in New York and LA. “I’m still searching for a home. It’s a lifelong theme.”

Idaho, Van Sant’s third film, fused other themes from Van Sant’s previous movies. Mike and Reeves’s Scott are best friends and sex workers, whose lives are an endless loop of predatory clients, post-coital meandering and parental angst. They have distinct differences. Scott is straight and comes from money; sex work for him is as much about survival as it is about rebellion. Mike isn’t sure how he identifies, but craves love, family and stability, all of which have been withheld from him since birth. He is like Bambi emerging from life’s chaos; Phoenix is so vulnerable that it stings.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

The film is a palimpsest of ideas. Scott’s story is loosely adapted from Shakespeare’s Henry IV, about an errant prince who goes wayward and then back again. There are grand monologues, dialogue imported directly from the Bard, sex scenes depicted as nude tableaux and porno mag covers that come to life. When the film was first unveiled at the Venice Film Festival in 1991, Van Sant remembers it being polarising. Even close friends would tell him they liked certain elements of the film more than others. “A lot of people didn’t like the Shakespeare, but also a good friend of mine was a real Shakespeare expert, and he was like, ‘It just didn’t work for me’,” Van Sant recalls with a chuckle.

Critics were generally kinder – or at least more accepting of its tonal eccentricity. “Idaho, in its subversive way, almost qualifies as a romantic comedy, except that its characters are so forlorn,” wrote The New York Times in 1991. “Despite its formlessness,” wrote The Washington Post, “Idaho does have narrative momentum in the beginning … It slows, eventually seems to stall, yet never once does its stunning, pristine quality flag.”

As the years went by, Idaho would become a touchstone of New Queer Cinema, an era of independent gay film at the top of the Nineties that simmered with sex, glamour, subversion and violence. It’s also one of the more romantic films of that period, with Mike’s pining for Scott now essential to its overall legacy. In its most open-hearted scene, Mike sputters a confession of love by a campfire. “I mean, for me, I could love someone even if I, you know, wasn’t paid for it,” Mike says. “I love you, and… you don’t pay me.” Mike’s voice seems to crack, his eyes locked on the ground, as if too scared to look at Scott’s expression. “I really wanna kiss you, man.”

Van Sant hadn’t intended for Mike to be gay when he first wrote the film’s script. Instead, he’d become intrigued by the idea of young men who were “gay-for-pay”, and capable of divorcing their sexual orientation from the physical act of sex. It was Phoenix who insisted on reworking the character, and more or less scripted the dialogue for the campfire scene himself. Before filming, he’d been allied with ACT UP, an organisation devoted to grassroots activism for people with HIV/Aids, and had developed a close friendship with a former street kid turned activist named Matt Ebert. “He talked River into making his character gay,” Van Sant says. “Because it would serve as a political act, an actor with his position in Hollywood playing a gay character.”

“I think it’s very important for the gay community to have random characters that represent nothing more than people,” Phoenix told The Face in 1992. “I think it’s part of a wave that will set a precedent of some sort, so that you’ll no longer need a label.”

Phoenix walked so the Heath Ledgers and Timothée Chalamets of the world could run, a by-most-accounts heterosexual actor and pin-up playing a gay character with compassion and care. Intentionally or not, his performance also understood the queer experience in its broadest terms. In his wide-eyed naivety and bursts of learned strength, he captures the feeling of being an outsider looking in, of having weathered very specific pain, and, out of necessity, forever searching – for love, for family, for home. That Idaho has been passed down through the generations, a seminal work worthy of endless discovery, speaks to its power.

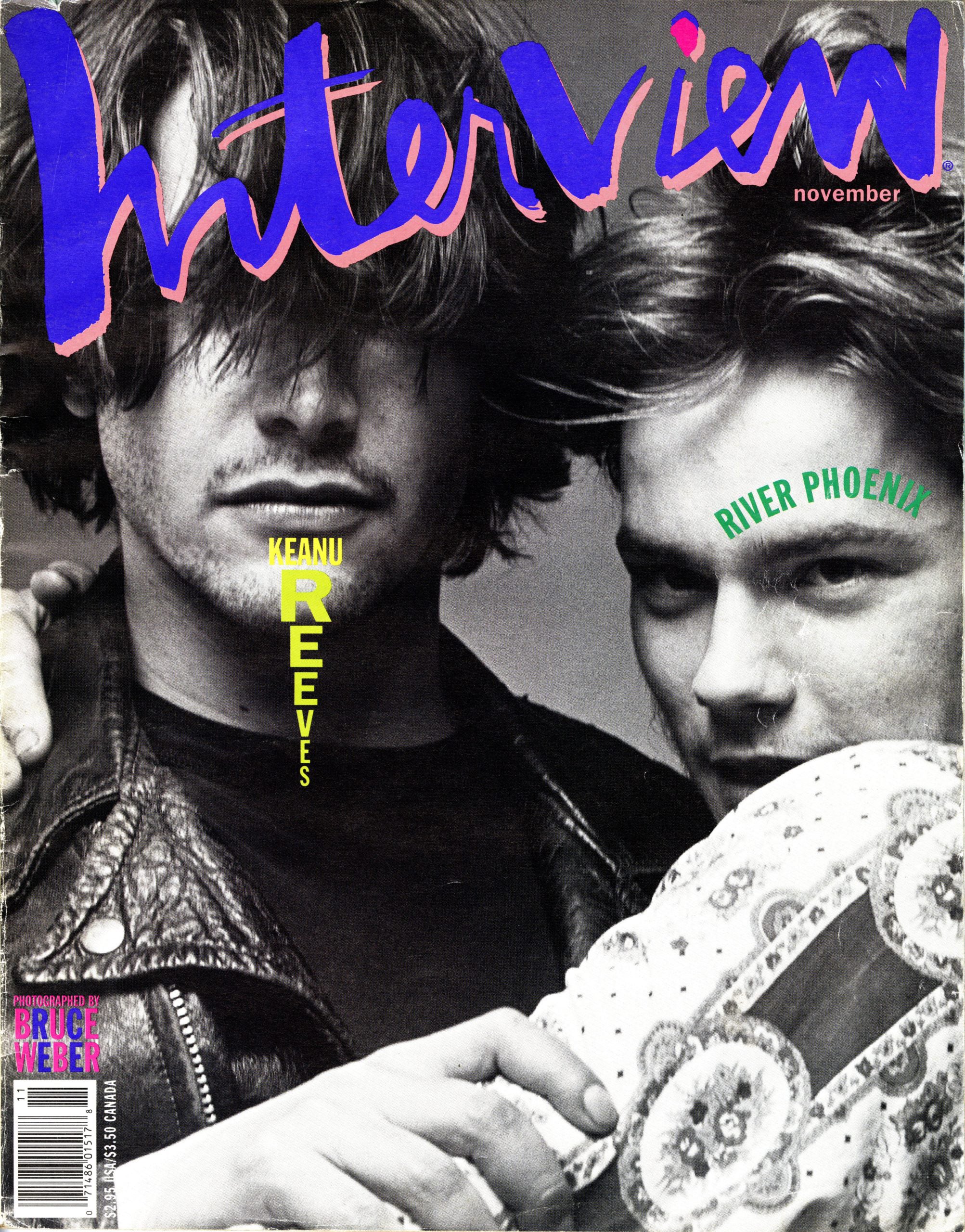

It also helps that both Phoenix and Reeves are remarkably, timelessly good-looking here, all fresh faces, pouty lips and sharp cheekbones. “For me, they were people that I initially only knew through images – from films or occasionally some place in the media,” Van Sant says. “I knew that they were really talented, and they were also sort of profoundly beautiful.”

It was an asset, along with their status as Hollywood heartthrobs. On set, though, Van Sant quickly separated their rising star power and appearance from their actual work. “I wasn’t constantly telling them how beautiful they looked,” he jokes. “You have to be business-like, you can’t become their fan rather than their director. Instead they became my compatriots.”

The film’s shoot was a hub of creativity, but also difficult. Phoenix, Reeves and the rest of Idaho’s cast and crew would regularly hold parties at Van Sant’s home, and became so rambunctious that Van Sant temporarily moved out. There was occasional tension between Phoenix and Reeves, too. They were close friends and had worked together before – on the black comedy I Love You to Death in 1990 – but had very different approaches to acting.

“River really liked to invent and make things up [in the moment],” Van Sant remembers. “Keanu’s orientation was to preserve the author’s words. He was a little bit like a stage actor – if you’re doing Samuel Beckett, you don’t start making up paragraphs on your own. Keanu was brilliant when he improvised, though. I would tell him that, but he wouldn’t believe it. River, on the other hand, was in his element. He knew that the best films are made up of accidents.” On the set of Dogfight, a coming-of-age drama he made right before Idaho, Phoenix had accidentally burnt himself with a cigarette in the middle of a scene. “The director said cut but River was like, ‘No, no, don’t cut, this is great!’ Whatever happened, River was into it. I think Keanu was amused by it, but he also wanted to be more traditional.”

“Shooting was a very intense experience,” Reeves told Interview Magazine in 1991. “I had just finished Point Break and was still into my character. I felt a bit of anxiety about Idaho. I was overwhelmed at what I had to do – it was like, ‘Oh, no! Can I do this?’ I was afraid. But Gus and River made me fit in. Said, ‘Let’s do one bitchin’ movie’... I was introduced to so many elements through the guy I was playing. Real people. My imagination. Gus’ interpretation. Shakespeare. It was rich! And it was just bottomless, man. You could go as far as you could go.”

If it took Reeves a while to get on the film’s wavelength – Van Sant thinks it was insecurity about his own ability – Phoenix and his director were creatively simpatico, and intended to work together over and over again. Prior to Phoenix’s death, Van Sant had entertained casting him in a “young Andy Warhol” film. He’d also eyed Phoenix for the role of politician Harvey Milk’s lover Cleve Jones in a Milk biopic – Robin Williams was attached to the leading role at the time. The film would fall apart, only for Van Sant to revisit it years later with actors Sean Penn and James Franco. As for Idaho, Van Sant has never struggled to watch it, even if it ended up being one of Phoenix’s final films.

“A number of years went by before…” he says, his voice dropping to a whisper. “It was three years after shooting. I kept in touch with River and he was a good friend. We had wanted to do all these different things together. But a lot of time had passed between Idaho and his end.”

In the final scene of the movie, Phoenix’s Mike is back on that dirt road again, gazing at the distance and slipping between reality and dreams. “I’m a connoisseur of roads,” he explains, as Van Sant’s camera spins around him. “I’ve been tasting roads my whole life.” He closes his eyes and opens them again, his sentences chopped into short, staggered words as he begins to lose consciousness. “This. Road. Will never. End. It probably goes. All. Around. The world.” And with that, he fades away.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments