How Double Indemnity planted the seeds of the true crime craze 80 years ago

As Billy Wilder’s film noir marks its 80th anniversary, Geoffrey Macnab looks at the story behind a dark classic that was decades ahead of its time

Double Indemnity has it all. It is a film about love, sex, murder, and jealousy – with a splash of insurance fraud thrown in for good measure. And yet, Billy Wilder’s 1944 noir masterpiece, released in US cinemas 80 years ago this week, tackles these weighty and often salacious themes with the utmost matter-of-factness. A contemporary reviewer described it as having “the frigid thoroughness of a coroner’s report”.

“It was a picture that looked like a newsreel. You never realised it was staged,” director Wilder later remarked to fellow filmmaker Cameron Crowe. Wilder’s protagonists aren’t gun-toting psychopaths, gangsters or bank robbers. They’re not private eyes or hardboiled cops, either. They’re middle-class Americans doing unspeakable things. Double Indemnity’s two leads – an insurance salesman (Fred MacMurray) and his married lover (Barbara Stanwyck) – evoke an audience’s sympathy as well as its disgust. Lines between heroes and villains are deliberately blurred.

Film historians have long acknowledged Double Indemnity as the quintessential film noir – a movie that (as Martin Scorsese put it) “revealed the dark underbelly of American urban life”. Looked at from today’s perspective, Wilder’s drama also seems to be a forerunner of all those productions we now watch avidly about ordinary people committing extraordinary crimes – Tinder swindlers, family murderers, hatchet-wielding hitchhikers and the like.

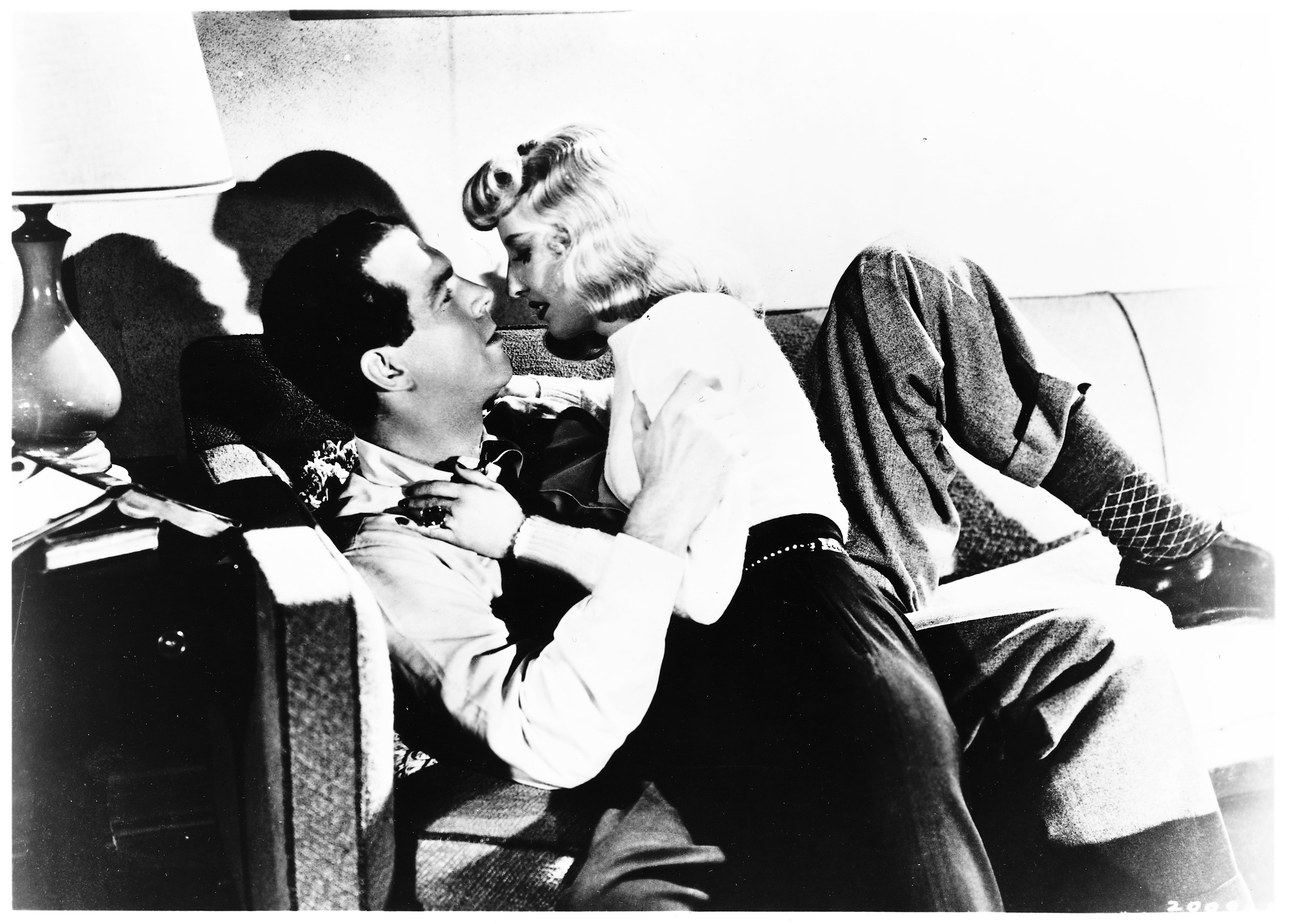

Stanwyck is given one of the great movie entrances: we first see her as the pouting Venus at the top of the stairs, greeting the insurance hack who has turned up uninvited at her house in the Hollywood hills. Wilder told Stanwyck to “look cheap” as the stay-at-home housewife, Phyllis Dietrichson. That’s why she plays the part with a blonde wig. The first time we see her, she is dressed only in a towel. Her hair gleams in the light. She explains to the salesman Walter Neff (MacMurray) that she has just been “taking a sunbath”.

The couple exchange flirtatious come-ons. “If you wait till I put something on, I will be right down,” she tells Neff. When she walks down the stairs, he can’t take his eyes off her legs and that “honey of an anklet” she is wearing. He makes a pun about leaving her “not fully covered” (referring to the insurance policy, not her lack of clothes).

Wilder co-wrote the script with crime novelist Raymond Chandler, basing it on James M Cain’s 1943 novella (first published in serial form in 1936). Cain had been inspired by the real-life case of New York housewife Ruth Snyder who, in 1927, had joined forces with her lover, corset salesman Henry Judd Gray, to kill her husband. (This bungled murder also partly inspired Cain’s earlier novel, The Postman Always Rings Twice).

Ruth was executed in Sing Sing prison in January 1928. An enterprising journalist called Tom Howard (the great-grandfather of Ted Lasso actor Jason Sudeikis) smuggled in a camera, attached to his ankle, and took a notorious snap of her on the electric chair. The image appeared in tabloid the New York Daily News the following day.

Cain had been a journalist in New York at the time of the Snyder trial, and knew the case inside out. Double Indemnity, though, is set in the wide open spaces of Los Angeles. It’s a story in which murder famously “smells like honeysuckle”. Neff is a clean-cut, well-spoken professional who throttles to death a man he has barely met. In the first minute of the film, he is shown driving erratically to his office at dead of night, lighting himself a cigarette and then talking into a Dictaphone. Wounded and sweating, he records a memo for his boss, the claims investigator Barton Keyes (Edward G Robinson), whom he regards as a mentor and father confessor.

Neff also gives away the entire plot only moments after the opening credits. “Do you want to know who killed Dietrichson? I killed Dietrichson... yes, I killed him; killed him for money and for a woman. I didn’t get the money and I didn’t get the woman,” he says. Then we’re into the flashback. “It all began last May...” starts the famous voice-over.

One of the most striking aspects of the movie is that such risqué material was passed by the censors. Wilder and his team were very careful to make sure that Stanwyck’s towel didn’t rise above her knees. By jumping in at the end and using the elaborate flashback structure, they were able to signal both that the killer was remorseful and that he had got his comeuppance. Nonetheless, they don’t skimp on the brutality or the eroticism.

“It was very influential in terms of the noir movement, but also in true crime,” writer-producer Alain Silver, co-author of a new book about Double Indemnity, tells me. “The most important thing about Double Indemnity was, despite the very explicit particulars in the Hays [Hollywood censorship] Code that say you cannot make criminals sympathetic, this is what the filmmakers do... you go with protagonists who are adulterers and murderers. You may not actively root for them, but you still empathise with them and what they go through. You share their moments of suspense.”

Double Indemnity was one of the first Hollywood films to exploit the power of the banal. The film’s swirling Miklós Rósza score gives us the sense that we are watching a torrid melodrama about human beings at the edge of the abyss, but the key scenes play out in deliberately dreary settings: grocery stores, offices and living rooms. (A final scene of Neff going to the gas chamber was cut out partly because it would have taken away from the ordinariness of the rest of the movie).

As in so many of today’s true crime stories, the throwaway details are often the most chilling: the car that doesn’t start; the chit-chat that Neff has with a friendly stranger in the observation carriage of a train minutes after the murder takes place. Logistics are foregrounded. We learn that it takes a lot of planning to have an extramarital affair, and even more to plot a murder. The killing itself isn’t shown directly. Instead, as her husband is strangled to death on the seat alongside her, Phyllis is seen in a big close-up behind the driving wheel, staring ahead, an inscrutable expression on her face.

Double Indemnity was marketed as a twisted romance. Cain called it “more of a love story than a murder story”. But after the killing, the romance sours. Phyllis and Walter become increasingly furtive and paranoid figures. Inevitably, they turn against each other.

Stanwyck’s character has often been described by critics as the archetypal film noir “spider woman” who entraps her male prey with the promise of sex and money. “I’m afraid to go home with her. She’s such a bitch,” Stanwyck quipped to reporters after watching a preview of her own movie. Other screen sirens, from Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct to Rosamund Pike in Gone Girl, owe an obvious debt to the character.

An alternative reading, though, is that Neff is luring Phyllis to her doom rather than the other way round. She is in an abusive relationship, and he appears to be offering her a way out. As she says to him: “I loved you, Walter, and I hated him, but I wasn’t going to do anything about it, not until I met you. You planned the whole thing. I only wanted him dead.”

With his insurance agent’s acumen and cheap cunning, Neff arranges the killing down to the last detail. He takes a morbid pleasure in trying to deceive his friend and boss Keyes, who thinks he can always sniff out a fraudulent claim.

MacMurray was cast as Neff when other, better-known actors turned the role down fearful that playing a killer would hurt their careers. The wholesome charm he brought to his later Disney movies The Shaggy Dog (1959) and The Absent-Minded Professor (1961) is evident here. That’s what makes his performance so fascinating. He is playing a cold-blooded murderer, one who also eventually hits on the teenage daughter of the man he has killed, and yet he never loses the audience’s sympathy.

Double Indemnity isn’t the first Hollywood movie to have featured an everyman whose life takes a dark and morbid turn. Movie adaptations of naturalistic novels like Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy and Frank Norris’s McTeague also featured seemingly wholesome protagonists drawn to violence. The difference is that Walter Neff is “35 years old, unmarried, no visible scars”. Boredom drives him as much as lust, greed or family trauma. (It’s no surprise that French existential novelist Albert Camus was reportedly a big fan of James M Cain.)

For contemporary audiences, aspects of the film may seem very antiquated. “Bottom line, it’s a long time ago. Do you really identify with this guy using a Dictaphone, still wearing his hat?” Silver asks. Nonetheless, when he and co-author James Ursini held a recent signing of their new book after Double Indemnity screened at the TCM Festival, people came up to them and told them “how fresh” they found the film.

In an era when true crime documentaries, dramas and podcasts fill the airwaves, Wilder’s cautionary tale is as topical as ever. It was remade by Lawrence Kasdan as the even steamier Body Heat (1981). Richard Linklater has acknowledged it as a strong influence on his romantic comedy thriller Hit Man, which recently topped the Netflix charts. Human nature, then, hasn’t changed much. That heady mix of voyeurism, guilt, sex, murder and suspense offered by Wilder in 1944 is just as potent now as it was 80 years ago.

‘From the Moment They Met It Was Murder: Double Indemnity and the Rise of Film Noir’ by Alain Silver and James Ursini is available now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments