How the horror and trauma of the trenches gave the world its two greatest war poets

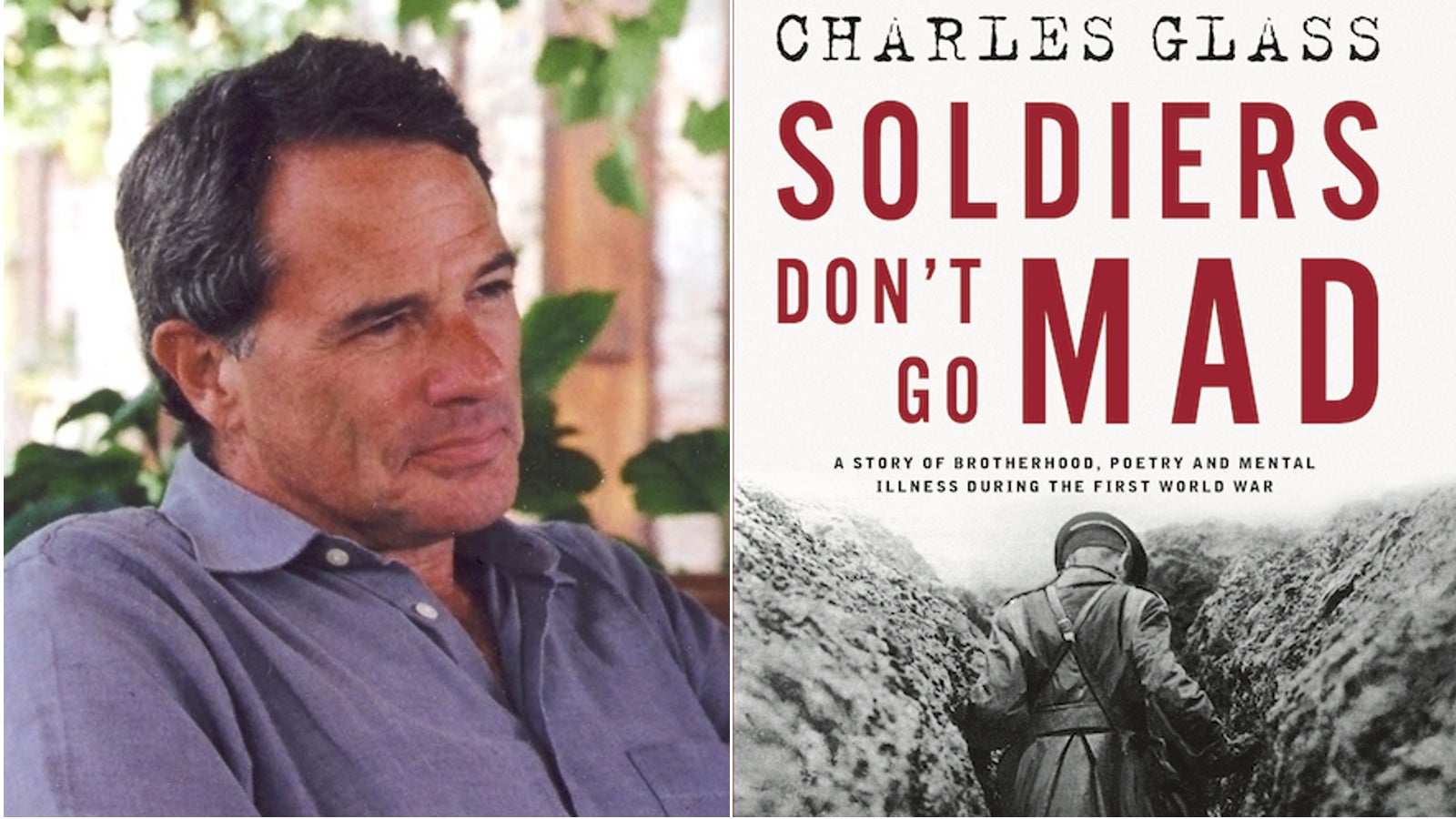

Huge numbers of soldiers were treated for shell shock during the First World War. The condition was little understood but from its suffering emerged the most remarkable and enduring poetry from Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. In an extract from his new book, ‘Soldiers Don’t Go Mad’, Charles Glass tells the story of their illness, treatment and friendship

All the armies in the First World War had a word for it: the Germans called it Kriegsneurose; the French, la confusion mentale de la guerre; the British “neurasthenia” and, when Dr Charles Samuel Myers introduced the soldiers’ slang into medical discourse in 1915, shell shock. Twenty-five years later, it was “battle fatigue”; by the end of the 20th century, it became post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

In December 1914, a mere five months into “the war to end war”, Britain’s armed forces lost 10 per cent of all frontline officers and 4 per cent of enlisted men, the “other ranks”, to “nervous and mental shock”.

An editorial that month in the British medical journal The Lancet lamented “the frequency with which hysteria, traumatic and otherwise, is showing itself”.

A year later, the same publication noted that “nearly one-third of all admissions into medical wards [were] for neurasthenia”, 21,747 officers and 490,673 enlisted personnel.

Dr Frederick Walker Mott, director of London’s Central Pathological Laboratory, told the Medical Society of London in early 1916: “The employment of high explosives combined with trench warfare has produced a new epoch in military medical science.”

The problem of soldiers’ mental health became a crisis in the summer of 1916 when General Sir Douglas Haig launched an all-out assault to break the German line in northern France’s Somme Valley.

It was not combat so much as slaughter. Between dawn and dusk, nearly 20,000 British soldiers died, while another 40,000 suffered wounds or went missing in action – the highest one-day loss in British military history before or since. The men and boys who straggled back to their trenches had witnessed unprecedented horror.

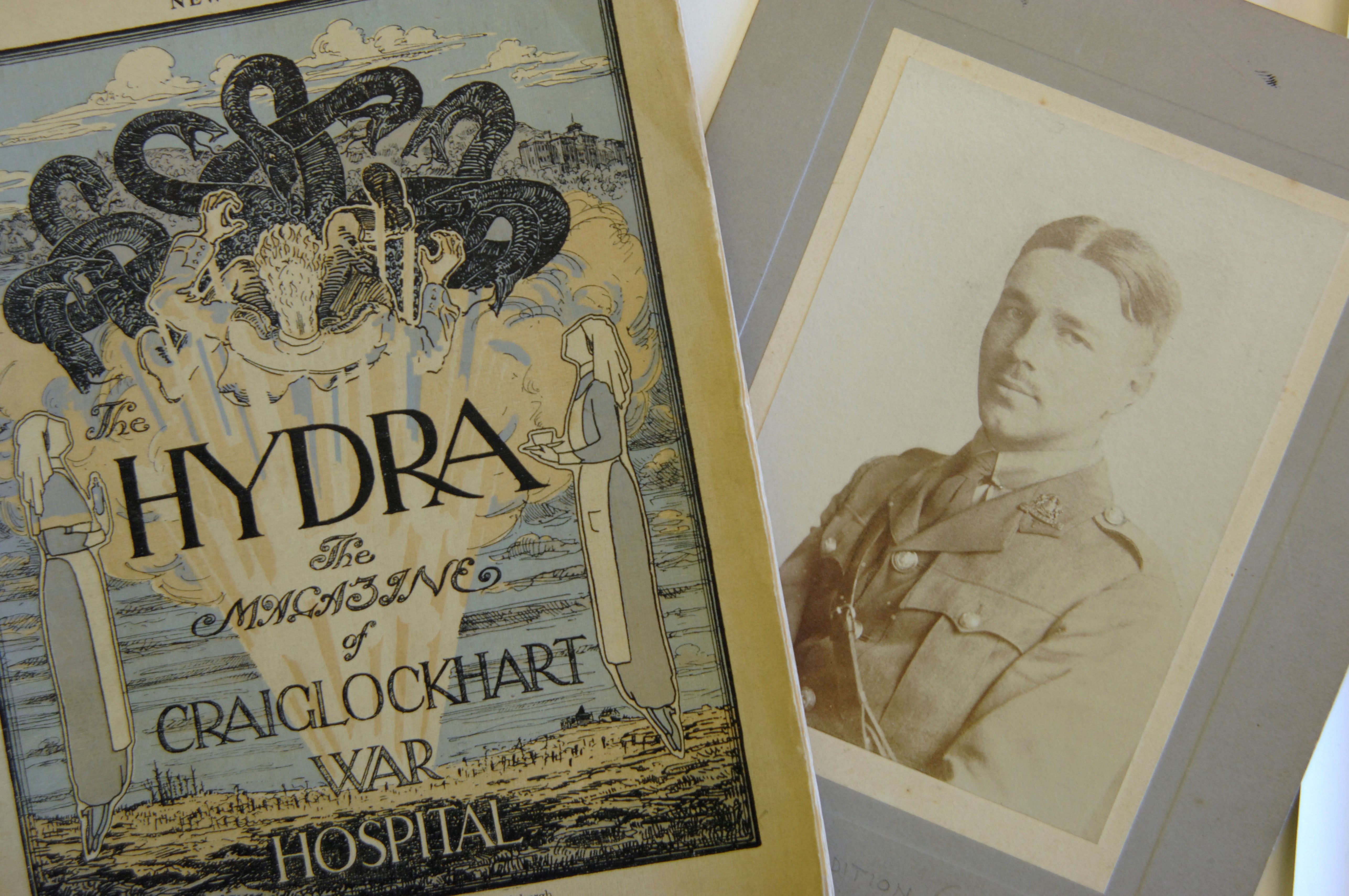

Many of the broken men recorded their experiences in diaries, letters, illustrations and poems. Two young officers treated for shell shock, Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, rank among the finest poets of the war. Yet, much of their verse would not have been written if not for their psychotherapy. Chance brought the two poets together and assigned each to a psychiatrist suited to his particular needs. These analysts acted as midwives to their works by interpreting their nightmares, clarifying their thoughts, and encouraging them in their creations.

Owen, who in another context might have been left to languish in trauma, benefited from intensive therapy under Dr Arthur Brock. Brock’s interest in science, sociology, folklore, Greek mythology, and nature studies accorded with Owen’s. It was Brock who expanded Owen’s horizons and gave him the self-confidence to tackle sundry outside tasks and restore his mental balance.

Sassoon, in contrast, enjoyed intellectual engagement with his psychiatrist, Dr William Halse Rivers, who did not trouble him with the outside activities that Brock imposed on Owen. Had Rivers treated Owen and Brock been responsible for Sassoon, this would have been a different story. Had both young officers been sent to different hospitals, they would not have met, and the poems they wrote would have been vastly different from the masterpieces the world knows.

Following the disaster of the Somme, the War Office opened new hospitals expressly to deal with shell shock and treat what had become an epidemic. The best was a place in Scotland called Craiglockhart.

*****************

Sassoon’s and Owen’s Medical Boards drew closer, 23 October for Sassoon and Owen a week later. Late October’s foul weather limited Sassoon’s golf time and left him to rehearse again his interior dialogue on the morality of fighting an unjust war. Owen meanwhile was profiting from a recovery that Sassoon attributed to Dr Brock, who “had been completely successful in restoring the balance of his nerves.” No longer trembling and stammering, a self-assured Owen ventured out of the hospital daily to see the many friends he had made over the previous four months. He charmed everyone he met, especially his friends’ children and the Tynecastle students. Maria Steinthal, the German artist who lived at 21 Saint Bernard’s Crescent with Leonard and Maidie Gray, invited him to sit for a portrait on 17 October. Owen was surprised when she completed a charcoal sketch of his features in five minutes. As was his custom, he played with Maria’s year-old daughter, Pixie, “the most exquisite bit of protoplasm that age I have handled”. He entertained Pixie, Maria painted, and “before tea, the complete rough likeness was done in oils!” The portrait would need more sittings, but even its incomplete form pleased Owen. A watercolour that Maria’s mother-in-law made of him did not.

While Owen was writing and socialising, Sassoon brooded. He wrote to Graves on 19 October, “My position here is nearly unbearable, and the feeling of isolation makes me feel rotten.” His friend Quartermaster Joe Cottrell wrote to him from Polygon Wood that the regiment’s circumstances were appalling. Friends were dying. Miles of mud, shell holes, and human and equine corpses covered the ground that Cottrell crossed each evening to bring up the rations. It was, he told Sassoon, worse than anything he had seen thus far. This as much as anything else afflicted Sassoon’s conscience. At last, he told Graves about his decision to return to France “if they will send me (making it quite clear that my views are exactly the same as in July—only more so).” Yet he felt he would be “returning to the war with no belief in what I was doing.” The letter contained a note of desperation: “O Robert, what ever will happen to end the war?”

The War Office was looking at Craiglockhart, in Sassoon’s words, “with a somewhat fishy eye.” Rivers told him that the army’s local director of Medical Services disapproved of the hospital and “never had and never would recognize the existence of such a thing as shell-shock.” The director must have shared the conventional opinion that mental patients were malingers feigning illness and that Craiglockhart was coddling them. It was no secret that Major Bryce permitted officers to wear slippers in the common rooms and did not prevent the staging of a dangerously socialist play. A full War Office inspection was inevitable, and Bryce received several weeks’ notice to prepare for one.

Forewarned, commanders of military hospitals, as of army bases, saw to it that staff scrubbed every surface and that the men polished brass buttons, shined shoes, and stood to attention for the examiners. Major Bryce, who Sassoon maintained “had won the gratitude and affection of everyone,” took the opposite approach. He believed that War Office inspectors should see the hospital as it really was. “He did this as a matter of principle,” wrote Sassoon, “since in his opinion a shell-shock hospital was not the same thing as a parade ground.”

The War Office sent a general, who found Craiglockhart in its usual state of managed disorder. The kitchen pans did not shine like mirrors. Bathroom floors were not clean enough to eat off. Patients’ uniforms lacked the required waist-to-shoulder Sam Browne belts. Doctors and nurses did not line up before the general to pay homage. Instead, they went about the business of caring for patients. The general, furious at the absence of discipline, decided that Major Bryce had to go. When the medical staff learned of their commandant’s dismissal, Rivers and other staff members submitted their resignations pending reassignment elsewhere. The patients were not told what was happening. Sassoon wrote that if he had been aware of Rivers’s intentions, he would not have done what he called “the stupid thing” when his Medical Board met.

Sassoon had good news for Owen when he appeared in the garret for tea on 22 October: there was no reason, as he had previously advised, to delay publishing a collection of his poems. He urged Owen to “hurry up & get what’s ready typed” so he could send the typescript to publisher William Heinemann. Owen would type his work, including six poems he had written that week, and give it to Sassoon. Sassoon’s gesture strengthened their mutual bond.

Rivers returned from the War Office in London to inform Sassoon that “two influential personages” would support his demand to serve at the front. Sassoon might at last return to what he called the “regions where bombs, mustard-gas, box-barrages, and similar enjoyments were awaiting me.” One of the “influential personages” happened to be a friend with whom Sassoon had played cricket before the war. The friend gave Rivers a letter that all but assured a positive result from his Medical Board. Sassoon needed only to show up and look sane.

The board convening on the afternoon of 23 October had a large number of cases to review. While the three physicians interviewed Lieutenant EJ Shater of the Royal Marines and several others, Sassoon waited in an anteroom. The lengthy delay made him “moody and irritable.” His thoughts turned to the Astronomer Royal’s invitation to show him the moon that evening through the lens of Scotland’s largest telescope. Losing patience, Sassoon checked his watch and “said to myself the medical board could go to blazes, and then (I record it with regret) went off to have tea with the astronomer.” He forgot about Rivers “and everything that I owed him”. Then, riding the tram through Edinburgh, he realised he had done something “unthinkably foolish.” Misfortune followed him to the Astronomer Royal’s house, where the telescope was not working. “So even the moon was a washout.”

The reckoning with his “father confessor” was not long in coming. Sheepishly, Sassoon proffered a “wretched explanation” that provoked Rivers, for the first time in their acquaintance, to intense annoyance. “The worst part was that he looked thoroughly miserable,” Sassoon recalled. When he pointed out that his desertion of the board did not imply reneging on his “decision to give up being a pacifist,” Rivers relaxed. Their eyes met. Sassoon, relieved, admitted he had been stupid to miss going back to the army merely for tea with an astronomer. Rivers “threw his head back and laughed in that delightful way of his” and agreed to arrange another Medical Board. A second board required the approval of a new commandant, who might be less sympathetic than Bryce.

Bryce left a void not only at the top but in the patients’ lives. The Camera Club, of which he had been president, “expressed its appreciation of the genial courtesy of the retiring President, Major Bryce, RAMC, on the occasion of his departure from the Hospital”. No longer would he play cricket and golf with the men, and the Saturday concerts would miss his lilting Scottish ballads. His replacement had much to live up to.

To succeed Bryce, the War Office turned to the fifty-seven-year-old president of Scotland’s Recruiting Medical Board, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Balfour Graham. His record as a military physician was impeccable. Son of a clergyman, he was born in Roxburghshire in southeast Scotland on 25 August 1859. After leaving the respected Kelso Grammar School, he studied art for a year before enrolling at Edinburgh University’s Medical School and earning his degree in 1884. There followed a period of public service: in 1887, volunteering as a surgeon in the Medical Staff Corps of the 1st Fifeshire Artillery Corps; in 1890, working for the Saint John Ambulance Association; and, in 1911, becoming public health examiner for Edinburgh’s Royal College of Surgeons. His army career saw him promoted to captain in 1889 and lieutenant colonel in 1908. At the onset of war in 1914, he became senior medical officer at the Western Command Depot and county director of the Scottish Territorial Red Cross Brigade. With no expertise in psychiatry, Balfour Graham was not an obvious choice to oversee Craiglockhart. The War Office must have seen the able surgeon and public health specialist as a solid administrator who could put the hospital into proper, military shape.

Dr Arthur Hiler Ruggles, as an American subject to his own chain of command, could not resign in protest at Major Bryce’s departure. He assumed Bryce’s responsibilities with the Camera Club, which he hosted every Sunday evening in his room. Ruggles went on treating neurasthenic officers and “saw many fine Scottish lads who had broken down dramatically at the front in those terrifying days of the war ... Among them were cases of acute dementia praecox [schizophrenia] and other disorders, all incorrectly lumped together as ‘shell shock.’” The men’s families visited them at Craiglockhart, telling Ruggles they wanted to take their sons and fathers home to the Highlands and care for them there. Ruggles opposed removing them from the hospital. “Nevertheless,” he noted, “many of the patients were taken out against advice and returned to the simple and familiar environment of the hills upon which they had been raised.”

The outcome surprised the psychiatrists. “I was in Scotland long enough,” wrote Ruggles, “to see many of these men return to the hospital for a follow-up visit, sufficiently recovered to have taken their place at home and to carry on actively and successfully their simple vocations.” He concluded that, despite their once debilitating symptoms, “they could recover when early removed from the stress and strain of danger, of frustration, and of battle complications”. As Rivers maintained, they were normal human beings reacting to the abnormal circumstances of war. Removed from them, they regained their health. It was an important lesson for Ruggles, but his mission in France would be to send American boys back into battle rather than to the nurturing environment of home.

‘Soldiers Don’t Go Mad’ by Charles Glass (£22) is published by Bedford Square Publishers and is available now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments