Obsessed with murder: how the creator of The Talented Mr Ripley came close to committing the crime herself

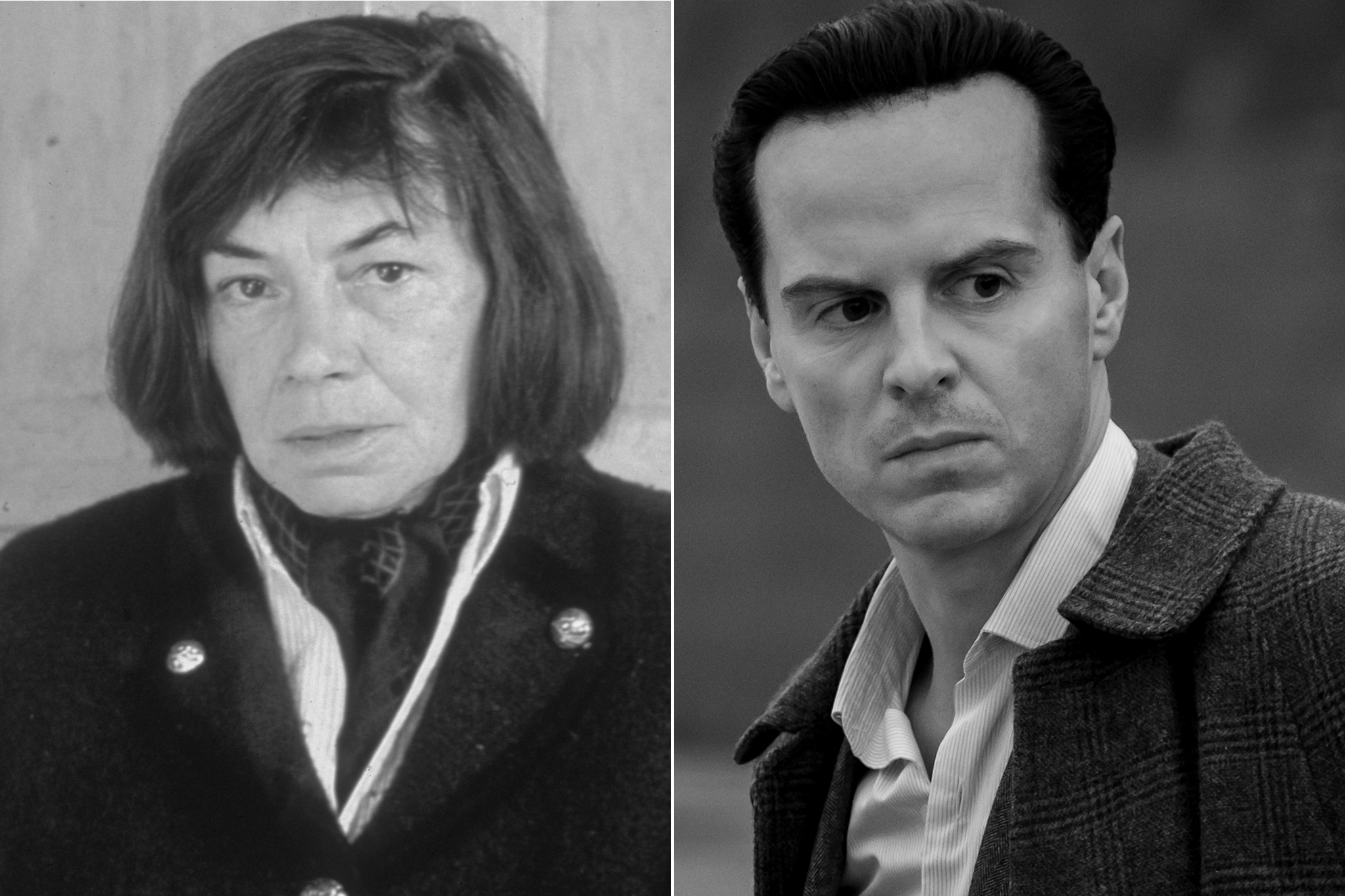

Patricia Highsmith was so enamoured with Tom Ripley – currently being played by Andrew Scott in the Netflix adaptation – that she’d sign letters using his name and describe murder as a ‘kind of making love’. But, as her biographer Andrew Wilson discovered, her most famous killer was a cover for her own darkest thoughts...

In June 1952 – two years before she started to write The Talented Mr Ripley – Patricia Highsmith had a dream about killing someone. In her nightmare, she was setting fire to a girl who resembled herself. As the flames began to engulf the naked body of the young woman, Highsmith felt guilty about committing the terrible crime. On waking, she tried to analyse the meaning of the dream. “I had two identities: the victim and the murderer,” she wrote in her notebook.

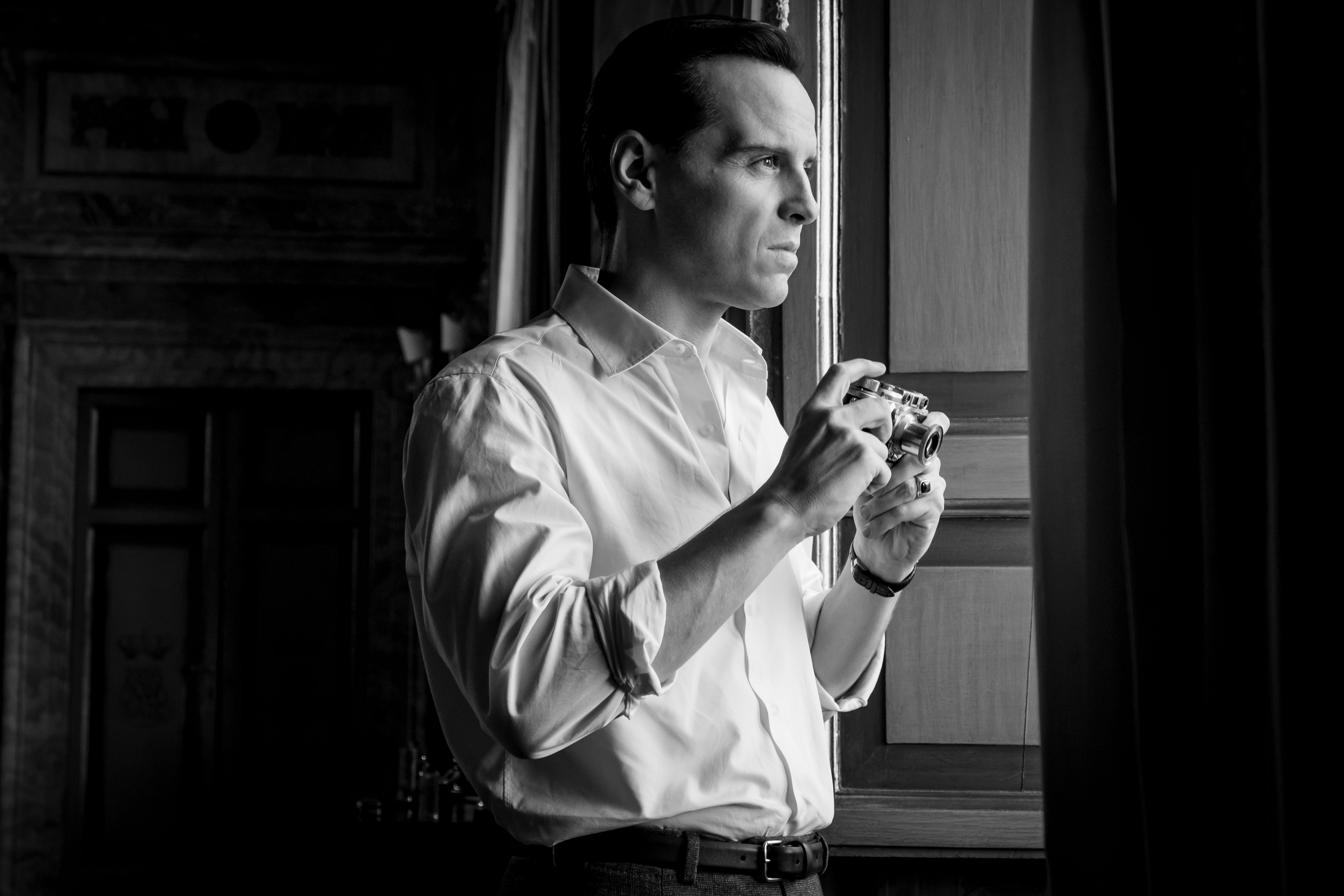

Highsmith – the creator of Tom Ripley, currently being captured beautifully by Andrew Scott in the new Netflix series Ripley – was obsessed with murder. Not only did it haunt her dreams, but – as I learnt during the process of researching my biography of the author – at times she became dangerously close to imagining committing the crime herself.

“Murder is a kind of making love, a kind of possessing,” Highsmith wrote in one of her diaries. “(Is it not, too, a way of gaining complete and passionate attention, for a moment, from the object of one’s attentions?)”

Anyone who has seen episode three of Ripley – in which Tom and his friend Dickie Greenleaf (played by Johnny Flynn) take a small boat out into the bay at San Remo, a trip that ends in murder – will understand the significance of these words.

“She was one of the great misanthropists, and there was something almost Swiftian about her,” her friend, the writer Roger Clarke, told me. She admitted that she found writing about psychopaths “easy”, and in later life she enjoyed flicking through the pages of A Colour Atlas of Forensic Pathology, a book that she described as containing colour photographs of “car accidents, murders and rape cases, the really shocking images that don’t reach the public”.

Highsmith identified with Ripley, the charming psychopath, to such a degree that she sometimes signed letters using his name, and talked about him almost as if he were a real person.

The painter Peter Thomson, who lived in Positano, one of the settings for The Talented Mr Ripley, recalled a conversation he had with Highsmith after they attended an all-night party on the beach of the Italian fishing village. “You remind me of Tom Ripley,” she told him. “It was as if she was talking about somebody she knew,” said Thomson.

Ripley was an embodiment of Highsmith’s darkest desires. “What I predicted I would once do, I am doing already in this very book (Tom Ripley), that is, showing the unequivocal triumph of evil over good, and rejoicing in it,” she wrote in her notebook in 1954. “I shall make my readers rejoice in it, too. Thus, the subconscious always precedes the consciousness, or reality, as in dreams.”

Highsmith’s preoccupation with the shadowy side of human nature began early. When she was a young girl growing up in Fort Worth, Texas – where she was born in 1921 – she had fantasies about murdering her stepfather, Stanley.

She said she was “born under a sickly star” – her mother, Mary, tried to abort her by drinking turpentine, and she felt a sense of guilt and alienation even as a small child. When girls her age were reading Little Women, she devoured books like Karl Menninger’s The Human Mind, a litany of case histories of “abnormal” psychology.

She realised she was attracted to her own sex, but was forced to repress these feelings. “I learned to live with a grievous and murderous hatred very early on,” she said. “And learned to stifle also my more positive emotions.”

The result fed the stew of her dark imagination. “All this probably caused my propensity to write bloodthirsty stories of murder and violence,” she said.

During her lifetime, Highsmith was celebrated for her 22 novels, suspense classics such as Strangers on a Train, Deep Water and the five Ripley books. She rarely gave interviews, and when she did, she was as closed and as secretive as one of the snails she kept as pets. It was only after her death in 1995, at the age of 74, that I discovered that Highsmith had recorded her most intimate – and violent – thoughts in a series of notebooks and diaries.

One day, in 1950, she took a train from New York to New Jersey to stalk a woman she had met – briefly – two years before. Highsmith had been working, temporarily, in Bloomingdale’s department store in Manhattan, when a glamorous blonde woman – the inspiration for her novel The Price of Salt, later republished as Carol – walked into the shop to buy a doll for one of her daughters.

Highsmith was immediately infatuated, and, after the woman left behind her delivery address, she travelled to her home and fantasised about her. “To arrest her suddenly, my hands upon her throat (which I should really like to kiss),” she wrote in her diary, “as if I took a photograph, to make her in an instant cool and rigid as a statue.”

Highsmith’s amoral endings left many shocked – in her books, the guilty often go unpunished. She loathed the form of the whodunnit, which she regarded as artificial and false. Rather, her approach was far more realistic, she said. “This is the way life is,” she once stated, “and I read somewhere, years ago, that only 11 per cent of murders are solved.”

The author’s identification with the criminal mind was no mere pose. In the summer of 1953, just before she started to plot out the book that would become The Talented Mr Ripley, she reached a crisis point with one of her partners, the sociologist Ellen Hill.

While in New York, Highsmith decided to break from Hill, a split that devastated the older woman. Ellen became so distraught that, after knocking back a couple of Martinis, she took an overdose of Veronal.

Instead of calling for an ambulance, Highsmith went out for a supper of hamburgers with a friend and left Hill to die. She arrived back at her apartment at two in the morning to find Ellen in a coma, a suicide note on the typewriter that read, “I should have done this 20 years ago.”

After she tried to revive Ellen with coffee and cold towels, Highsmith called for a doctor, who admitted her lover to a psychiatric hospital. The doctor gave Hill a 50-50 chance of survival, but instead of caring for her, Highsmith drove up to Fire Island with a friend. “I am escaping from hell, believing Ellen is dead at this point.”

Although Hill survived, she had to suffer the indignity of discovering that Highsmith had reworked her real-life suicide attempt into fiction. In her 1954 novel The Blunderer, Highsmith casts herself as the character of Walter, and Ellen as the neurotic wife, Clara. “Walter could not escape the fact that he had known she was going to take the pills,” Highsmith writes in the novel.

Walter ponders whether his actions – like Highsmith’s – could be interpreted as a kind of murder. “The suicide & Ellen’s character in the book,” Highsmith wrote in her diary, “I find very disturbing & too personal.”

As Highsmith aged, one of her friends called her “an equal-opportunity offender”. She had a twisted sense of humour – her agent Patricia Schartle remembered that the only time she had seen Highsmith laughing was when she saw a poster on the New York subway “where some creep had gouged out the eyes of the child”.

Highsmith famously said that if she saw a kitten starving on the street or an abandoned baby, she would choose to rescue the cat. “The morbid, the cruel, the abnormal fascinates me,” she wrote in her journal.

In Tom Ripley, she found her perfect mouthpiece – perhaps even her saviour. As her friend Clarke told me, “I could imagine her committing unspeakable crimes if she had no outlet, the outlet of her writing.”

Andrew Wilson is the author of ‘Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith’ (Bloomsbury, £16.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments