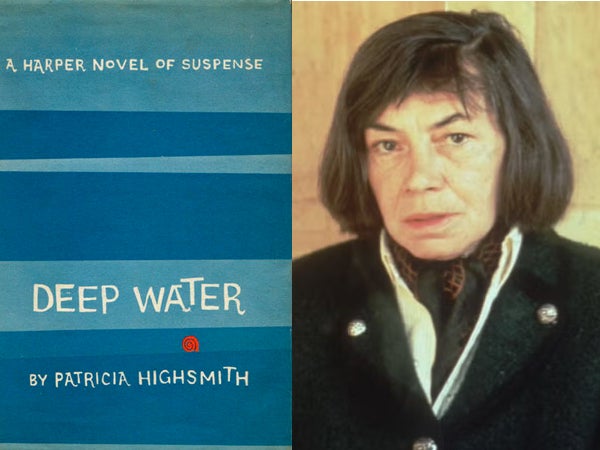

Book of a lifetime: Deep Water by Patricia Highsmith

From The Independent archive: Craig Brown sees in the reclusive novelist’s ‘psychopath heroes’ a writer who is deeply attuned to the strange rhythms of guilt, jealousy and fantasy that affect all of us in different ways

Staying in a house in Italy aged 19, having got to the end of a Henry James, I picked a paperback called Deep Water by a writer I had never heard of and read the first couple of sentences. “Vic didn’t dance, but not for the reasons that most men who don’t dance give to themselves. He didn’t dance simply because his wife liked to dance.”

Henry James it was not. But who could resist reading on? Back then, I had never read anyone quite like Patricia Highsmith: blunt, anxious, tense, paranoid, driven. Thirty-five years later, I still haven’t, though I have read any number of imitators.

After Deep Water, I read The Blunderer, and after The Blunderer, The Talented Mr Ripley. Vic, it emerged, is a prime example of what Highsmith fondly described as “my psychopath heroes”. They are driven to murder, and then have to live with the dread of being found out. If they have a forerunner, it is Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment.

What by turns motivates and paralyses Highsmith’s heroes is this dread, not of murdering, and certainly not of being murdered, but of being found out. It lay deep in the heart of her work and her character. In the years to come, I would interview her, or at least try to interview her, on a number of occasions, but she never gave anything away, always replying yes or no or maybe if she possibly could.

Clamming up was second nature to her. The only time I remember getting a rise out of her was when I called Vic a weak man. “But at least he had a go,” she replied, testily. “At least he HAD A GO!” She wanted me to give him due credit for having had the guts to kill his wife’s lovers.

She lived in her books, and, in many ways, through them. “Her writing saved her,” one of her friends told her biographer. “She knew that it stood between her and insanity... all those strange characters haunting other people, and thinking and fantasising about them – they were her. She WAS her writing.”

Throughout her life, she kept notebooks: by the age of eight, she was already fantasising about killing her stepfather. In her late sixties (she died in 1995, aged 74) she recorded a dream in which her mother, whom she disliked, primarily for her stupidity, cut off the head of one of Patricia’s ex-lovers and told her, “You will have to help me get rid of the body”, before coating the head in transparent wax.

Her novels are deeply attuned to the strange rhythms of guilt, jealousy and fantasy that affect all of us in different ways. I suspect that if they were less exciting – it’s quite possible to find you have stopped breathing in their more extreme passages – they would have been admitted into the stately canon of classics long ago.

But dreariness is commonly mistaken for seriousness, particularly in literary circles, so I imagine she will always be parcelled off as a genre writer. At least this will help her cover her traces: even in death, she will not be found out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments