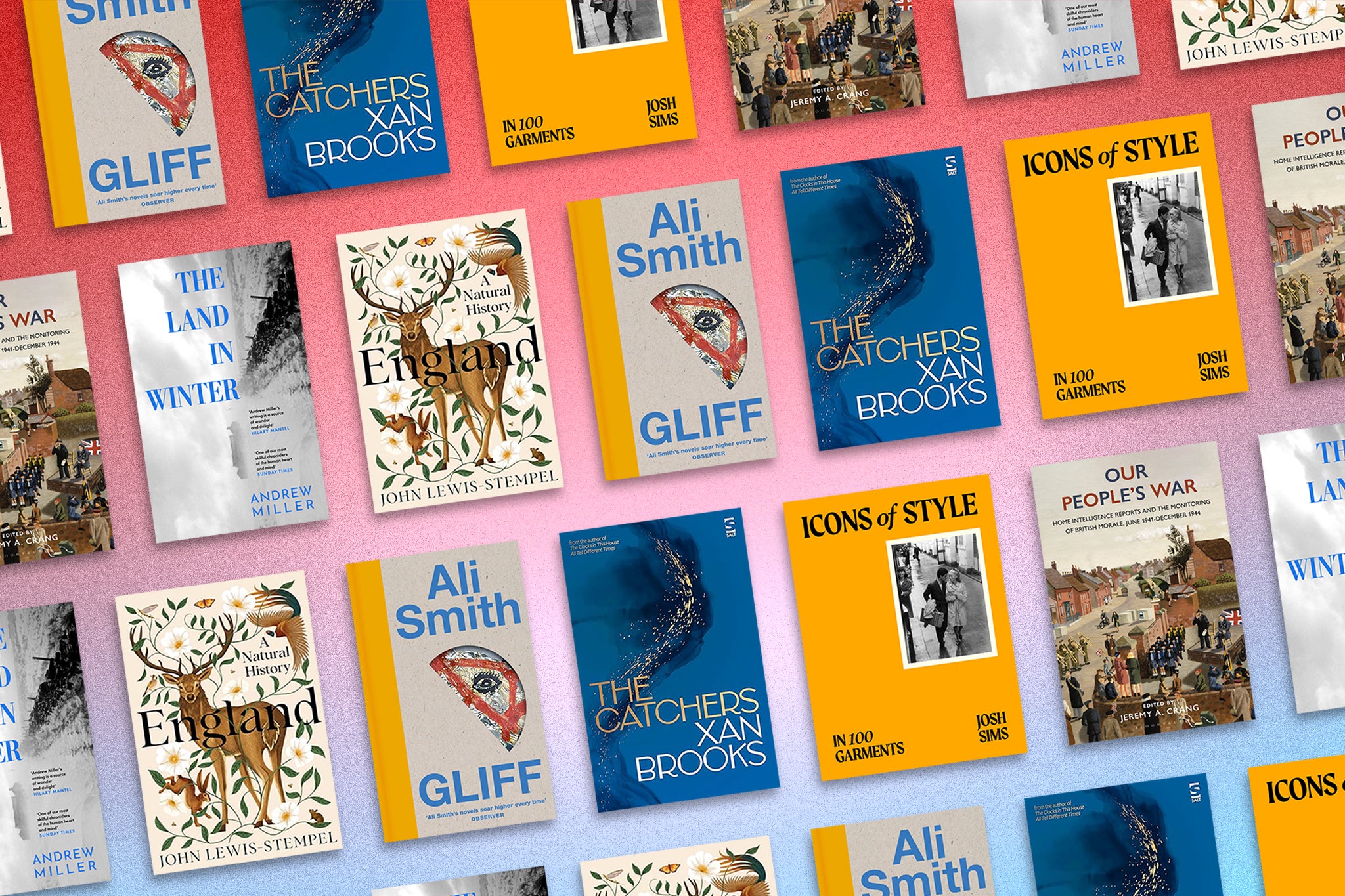

Books of the month: From Gliff by Ali Smith to The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller

Martin Chilton shares his October reading highlights

When Donald Trump talks of “poisoning the blood of our country” he is “channelling Hitler”, according to Gavin Evans, author of White Supremacy: From Eugenics to Great Replacement (Icon) – a deeply disturbing book that picks apart the dangerous, unscientific ideas behind racism. In his shocking opening chapter, Evans details the mass killing of 10 Black people in Buffalo, New York in 2022, and traces how manipulated beliefs can inspire alt-right killings. The book, incidentally, also covers the murder of British MP Jo Cox. White Supremacy is a grim but important book.

The lives of four groundbreaking women – Marie de France, Julian of Norwich, Christine de Pizan and Margery Kempe – are explored with great verve by Dr Hetta Howes in Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife: The Extraordinary Lives of Medieval Women (Bloomsbury), as the historian explains why they all, in very different ways, pushed back against the limitations placed on them by society.

A hearty recommendation for Robert McCrum’s The Penalty Kick: The Story of a Gamechanger (Notting Hill Editions), which tells the story of football’s most dramatic sanction: the penalty kick. The game-changing rule was first proposed by William McCrum, an amateur Irish goalkeeper and the author’s great-grandfather, and introduced in 1891. McCrum’s book is a fine social history of football and an original look at football’s frequently defining moments of high-stakes risk and chance.

Finally, two large-size books that will bring constant “dipping-into” pleasure are Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock’s Webb’s Universe: The Space Telescope Images That Reveal Our Cosmic History (Michael O’Mara), which is full of intriguing explanations and stunning images, and Simon Bradley’s Bradley’s Railway Guide: A Journey Through Two Centuries of British Railway History, 1825-2025 (Profile Books), which is a superb history of what is the oldest railway system in the world.

Novels by Andrew Miller, Xan Brooks and Ali Smith, and non-fiction books about nature, fashion and the Second World War, are reviewed in full below.

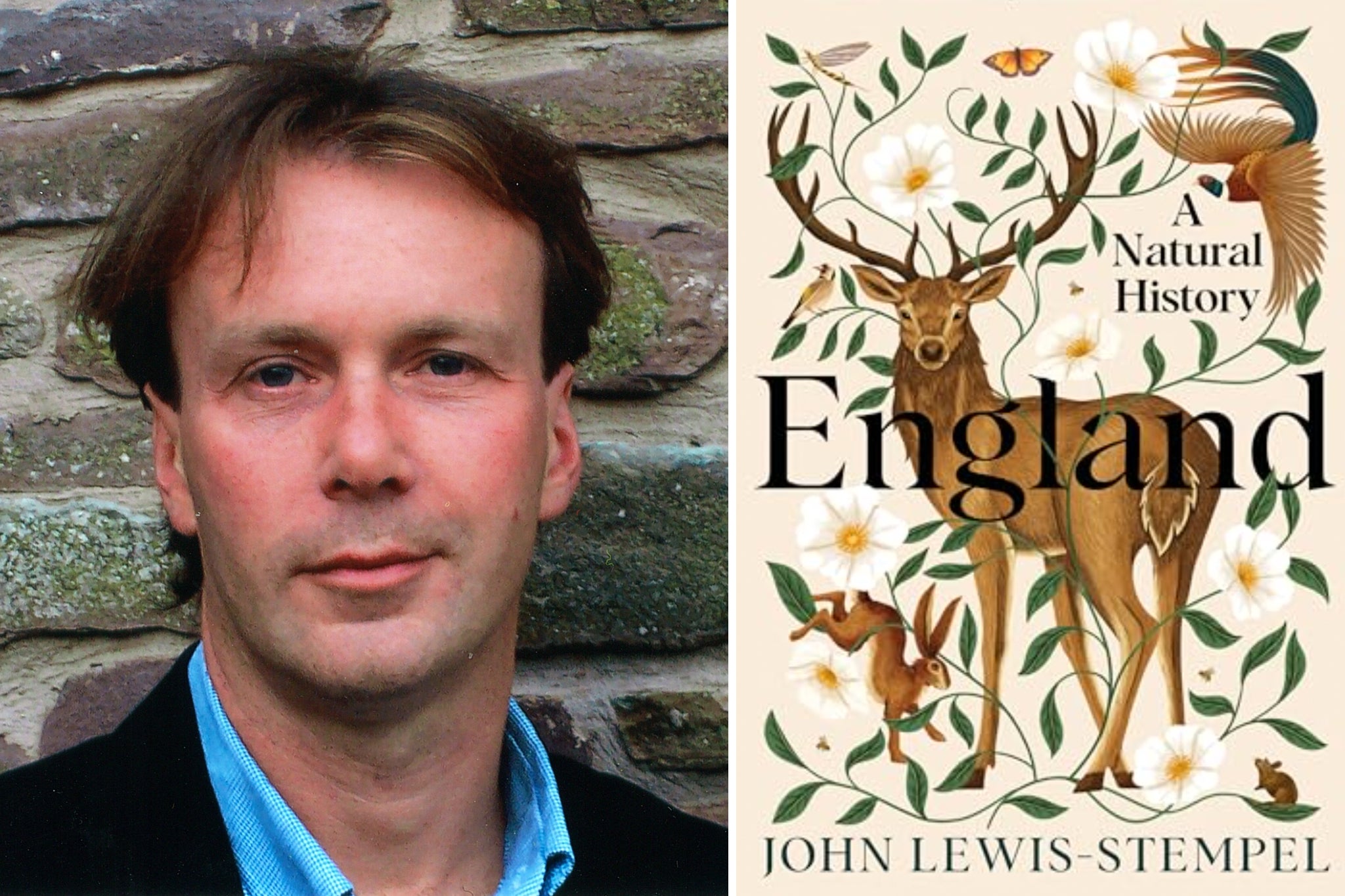

England: A Natural History by John Lewis-Stempel ★★★★☆

John Lewis-Stempel, a highly respected nature writer, meanders around England in his erudite and highly informative England: A Natural History. The 12 chapters – Estuary (Thames); Park (Richmond), Downs (Mount Caburn); Beechwood (Burnham Beeches); River (The Wye); Field (Herefordshire); Village (Helpston, Cambridgeshire); Moor (Spaunton); Lake (Crummock Water); Heath (Isle of Purbeck); Fen and Broad (Norfolk) and Coast (Portreath, Cornwall) – are packed with humorous, quirky details.

Among the many wonderful things to learn about are that smelt used to be fished in the Thames, about the prolific farting of the deer of Richmond Park (and that Shakespeare was apparently a “thrill-poacher” of deer), about the strange history of the beech nut and the fact that Lewis-Stempel, a traditional farmer, rubs factor 30 suncream into pale-skinned pigs to prevent them getting sunburn.

I also learned about the true character of rabbits. Did you, like me, think of rabbits as fluffy and cuddly? In fact, rabbit society is strictly hierarchical and female rabbits will kill the kits of rivals by dragging them by the scruff of their necks to the surface to perish. What’s up, doc?

There were less palatable sections to read, too, especially the “rivercide” mix of chemical spillage and sewage that is despoiling the 155-mile River Wye. “River days are good days”, remarks the author, recalling memories of cleaner and happier bucolic days for England’s waterways.

Lewis-Stempel’s latest book should make a brilliant gift for anyone who loves the countryside.

England: A Natural History by John Lewis-Stempel is published by Doubleday on 3 October, £25

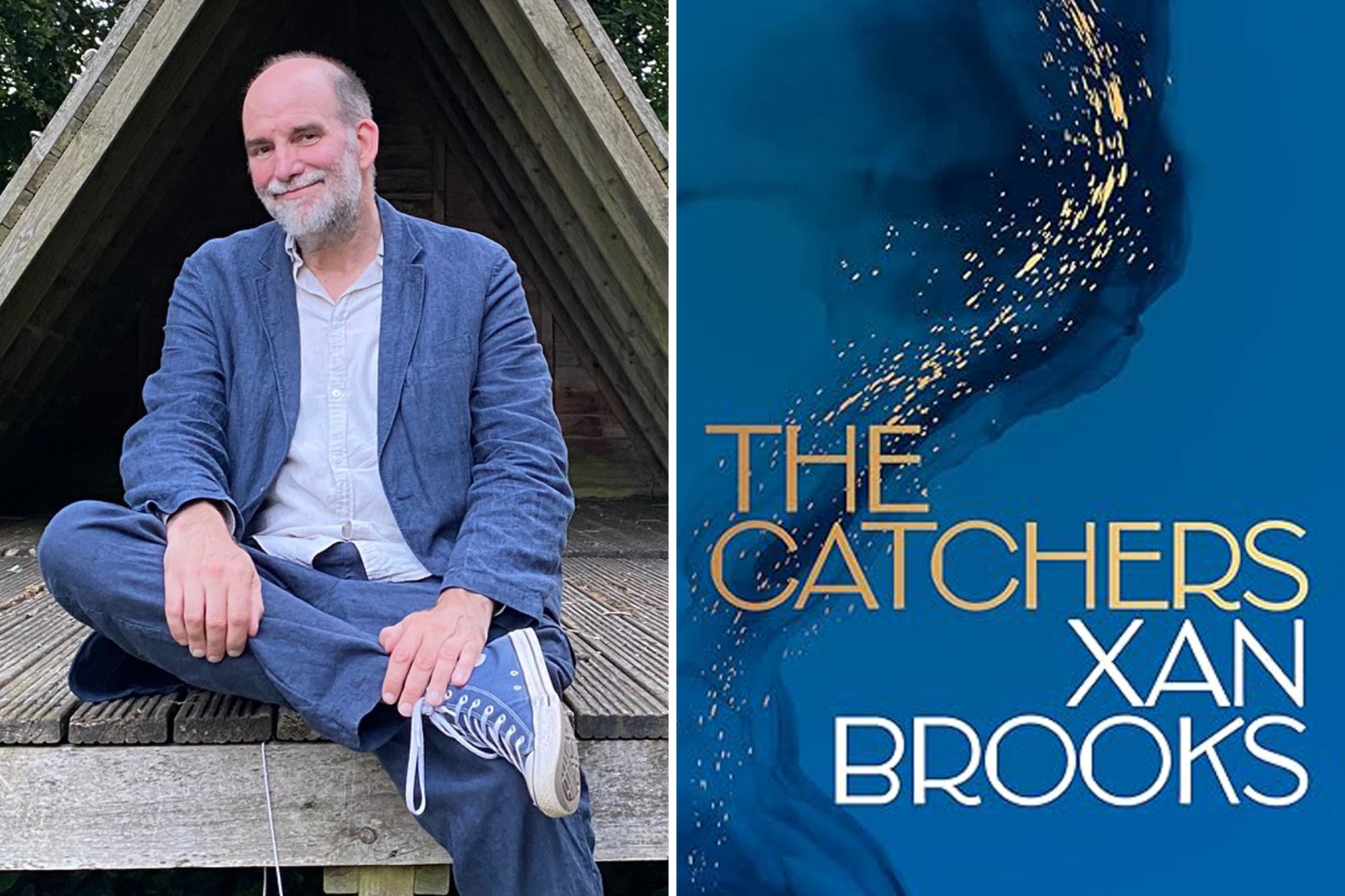

The Catchers by Xan Brooks ★★★★☆

The Catchers is set in 1927 and in part deals with the exploitation of Deep South Black musicians by white-owned record companies, at a time when a hit single earned small fortunes. In Brooks’s excellent novel, rookie song-catcher John Coughlin – one of the men who unearthed the unknown musicians, paid them a small one-off fee and returned to New York with their recorded work – is advised by an old pro (in terms that brought to mind a Death of a Salesman) to: “suck out the juice, pay your money and throw the pulp to the kerb”.

When Coughlin hears of a hugely talented teenage guitarist called Moss Evans, running bootleg liquor in the Mississippi delta, he sets off on an epic road trip to find him and record his magical music. He heads to the Deep South (a “savage country, pitiless and arbitrary”) just as a biblical storm brings death and destruction. The resulting road trip is full of strange and dangerous confrontations.

Brooks’s novel is hugely atmospheric, neatly capturing an era when it feels like “everything is accelerating”, and it brings to life a world of hustlers looking for the gold rush of a hit song in captivating style. The story is full of vivid, shocking characters – The Troller, Colonel Bird, the feral Grady Boys – and memorable descriptions (“straight-backed old women with windfall apple faces”.

The pulsating plot rattles along, rather like Coughlin’s old automobile, but this is also a tale with potent and disturbing things to say about profiteering and the racism that blights America. Brooks captures the magic of the music but leaves you fearing that reformed thief Coughlin is simply another “trader in flesh”.

The Catchers by Xan Brooks is published by Salt on 15 October, £10.99

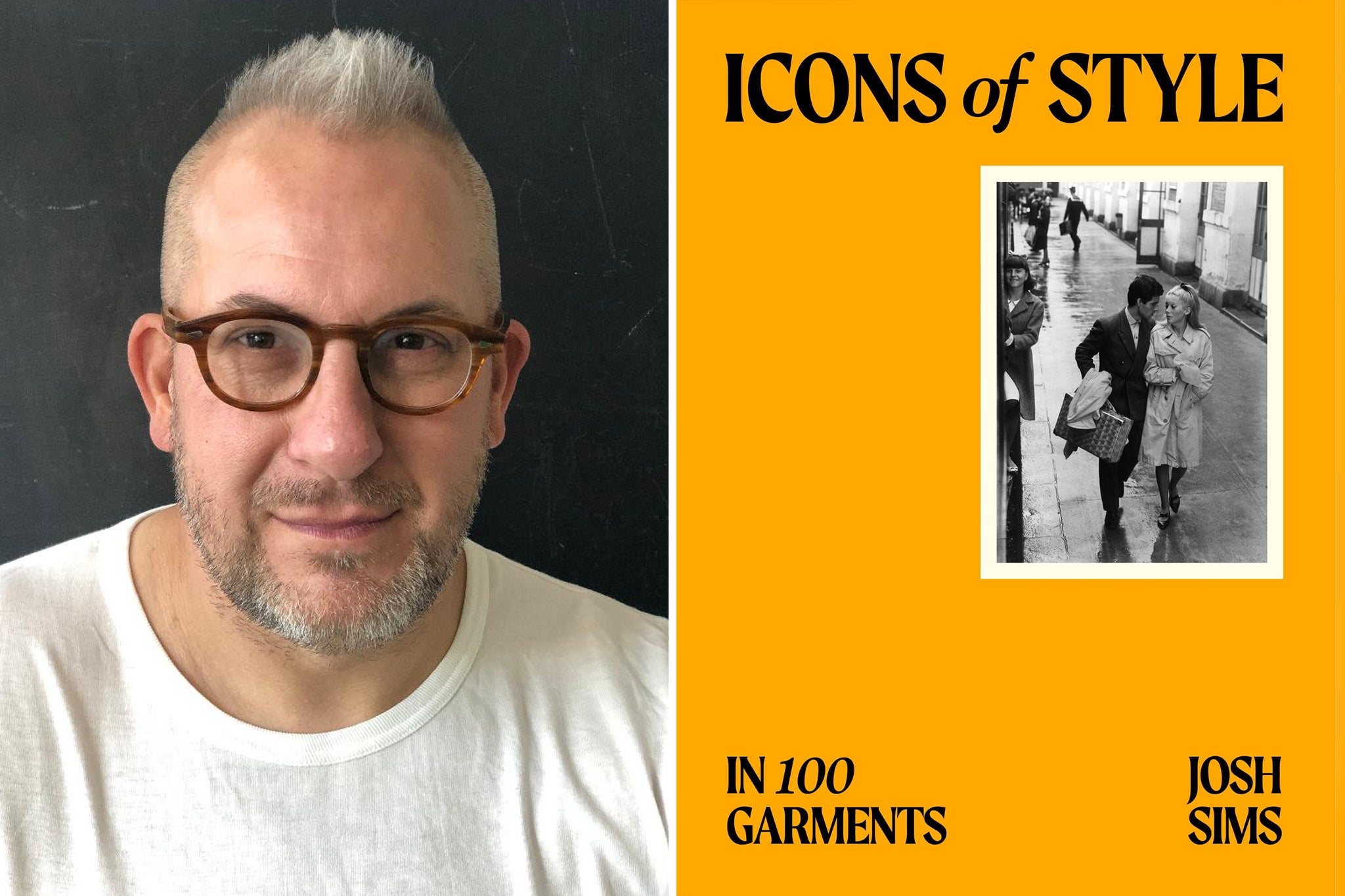

Icons of Style: In 100 Garments by Josh Sims ★★★☆☆

I’m probably what you would call “fashion-impaired”, so the chapter that appealed to me most in Josh Sims’s Icons of Style was “Sweatpants”, in which the author quotes Jerry Seinfeld’s advice to George Costanza: that wearing sweatpants is a sign you have given up on life. “You know the message you’re sending out to the world with those sweatpants? It’s ‘I can’t compete in normal society. I’m miserable. So I might as well be comfortable,’” Seinfeld tells his middle-aged, bald, loser friend.

The photographs in Icons of Style are delicious (especially of trendsetters such as Audrey Hepburn, Frank Sinatra and Marlene Dietrich) and Sims has an eye for quirky facts. For example, he informs us that Bing Crosby was refused entrance to an upmarket hotel because he was wearing a denim jacket, and that a man named Michael Fish created the kipper tie.

I thoroughly enjoyed repeated forays into Icons of Style and the book will also make a great present for anyone interested in the origins of the modern wardrobe. Although, to be honest, £30 for a paperback may not be the perfect fit for your pocket.

Icons of Style: In 100 Garments by Josh Sims is published by Laurence King on 17 October, £30

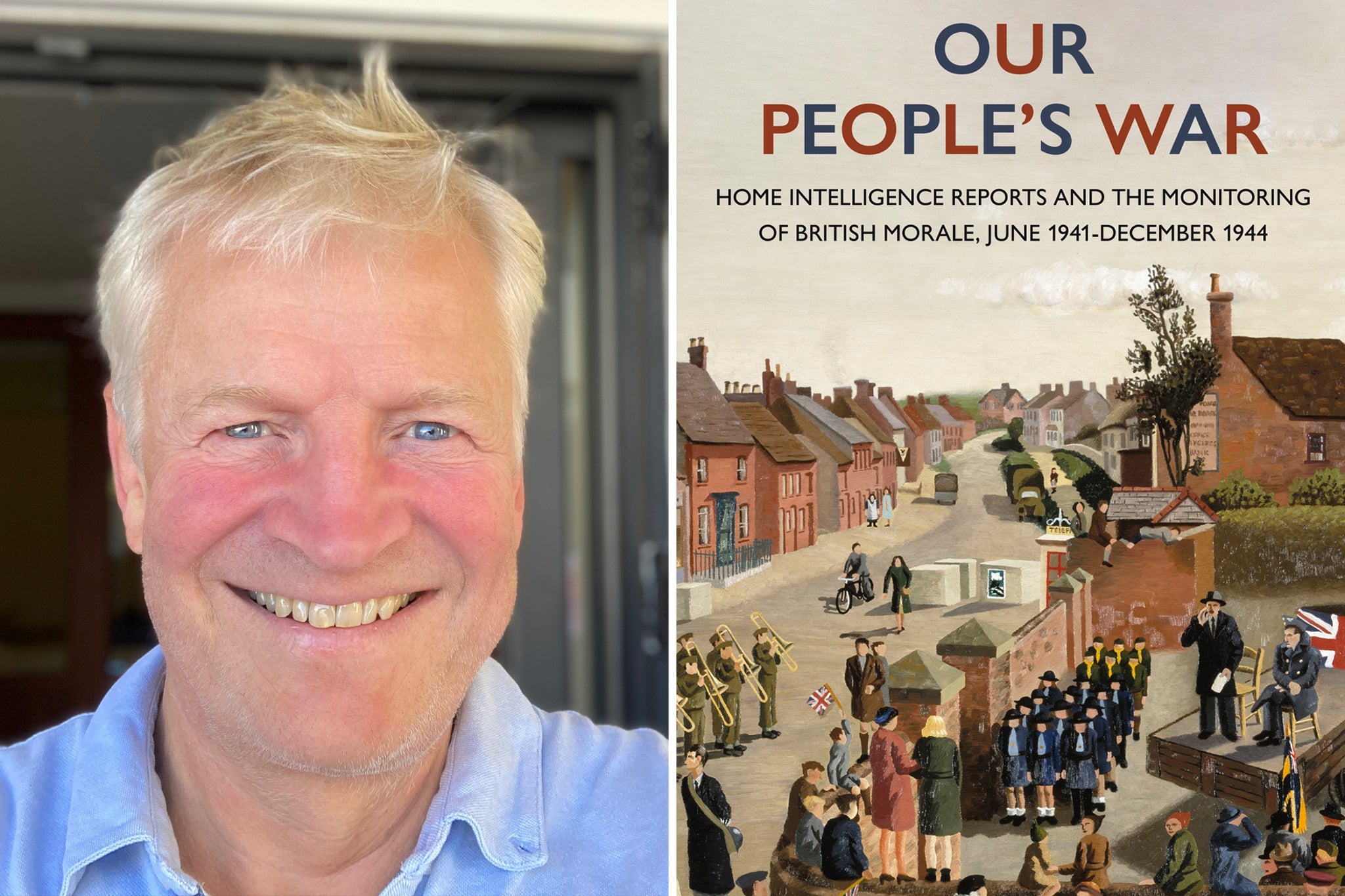

Our People’s War: Home Intelligence Reports and the Monitoring of British Morale, June 1941-December 1944, edited by Jeremy Crang ★★★★☆

In the 672 pages of Our People’s War, a nuanced and sometimes depressing picture of wartime Britain emerges, one very different from the spirited “Old Blighty battling-the-Blitz” cliches trotted out with such regularity.

In this follow-up to a 2011 book covering 1940, Jeremy Crang, professor of modern history at the University of Edinburgh, has edited a collection of wartime documents that monitored public opinion. According to the documents, organised by Home Intelligence, a unit of the Ministry of Information, the British public have a “gloomy tinge” and delight in “knowing the worst, coupled with a strange anxiety about not being told the worst”. Plus ça change?

Long before the fake news of social media, the British public lapped up rumours and false tales, whether it was about a German man dressed as a woman cutting electric cables in Liverpool, or Hitler buying up the world’s sardine stocks, or even rumours that Cornwall was about to be invaded.

Along with the constant preoccupations – rationing, bombing raids, food shortages and shopping queues, the futility of Home Guard duties, the shortages of doctors – the immense detail in the week-by-week state of the nation reports offers a compelling insight into hidden aspects of what it was like to live through the Second World War.

Surprisingly, problems with the quality of footwear were one of the greatest worries for ordinary people. Mums were worried about the “brutality” of army training and the government were concerned about the “great menace” of venereal disease, troubled that “lewd jokes” would nullify the effects of their health campaigns. There was also government concern for teachers, with reports identifying “inadequate school discipline due to large classes and teachers being overworked”.

The nasty side of wartime Britain is also apparent in the amount of antisemitism (“anti-Jewish sentiment runs very high in Brighton”) and that racism against Black people was also a problem. “In Norwich certain restaurants will not serve negroes,” documents note.

Another predictably dismal aspect is the constant sexism. In the account of American troops having “sexual relations” with girls as young as 14 (surely, this was simply rape?), often in telephone booths. “Blame of the girls is more widespread and stronger than of the men,” one Home Intelligence report notes. Instead of looking at punishing predatory men, the government instead focussed on the “landslide in morals” among young girls. They were also worried about the increased amount of alcoholism among young girls, blaming them for “disgraceful scenes” and thinking only of “dance halls, pictures and dogs”.

Our People’s War is a genuinely fascinating history.

Our People’s War: Home Intelligence Reports and the Monitoring of British Morale, June 1941-December 1944, edited by Jeremy Crang is published by Bloomsbury Academic on 17 October, £20

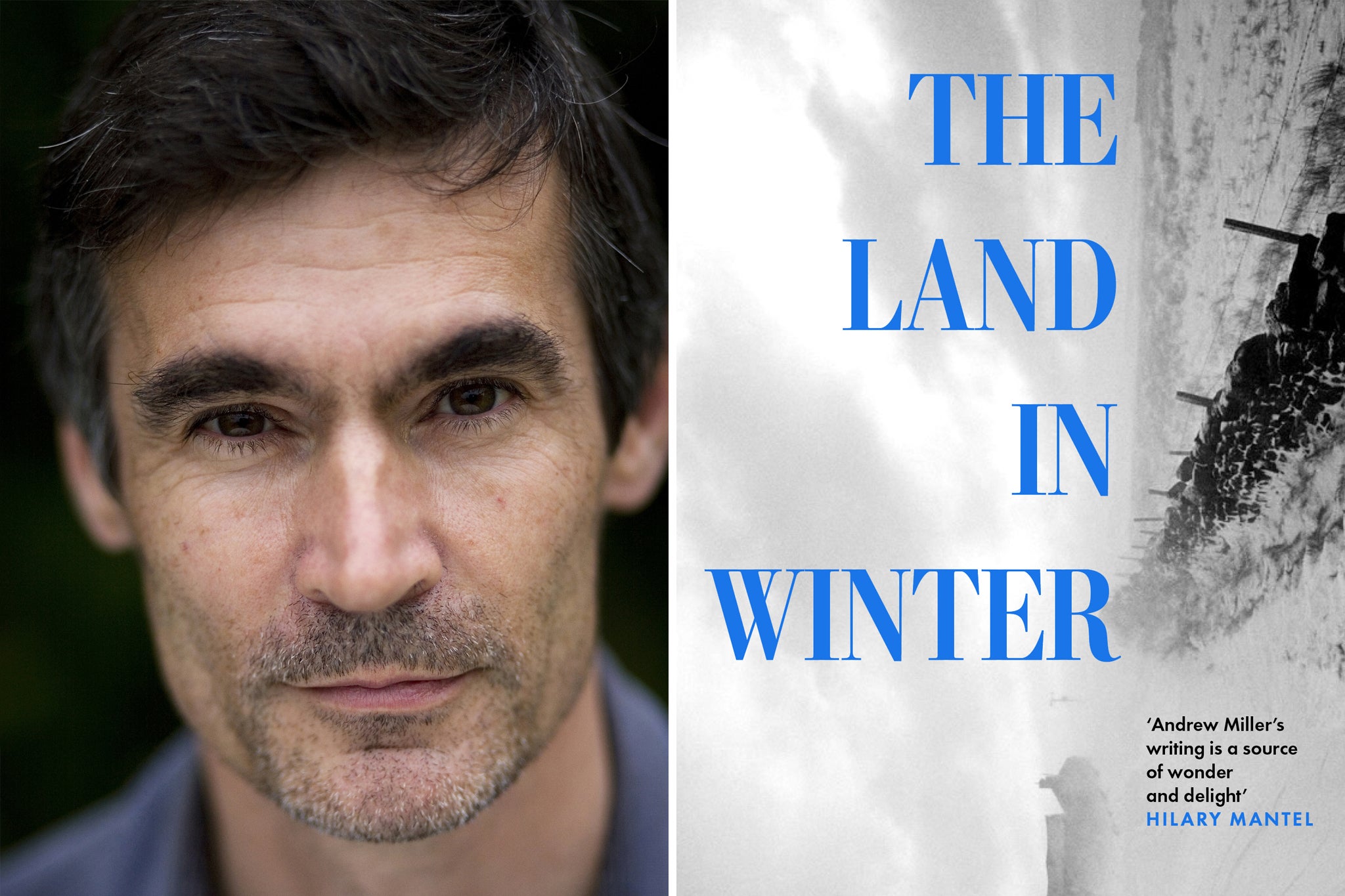

The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller ★★★★★

“There’s always a bloody price tag. Nobody gets away with anything,” says a minor character in Miller’s The Land in Winter, a delicate and devastating novel set in the West Country, around the bitterly harsh winter of 1962-1963.

The main drama centres around two pregnant neighbours – the volatile and damaged Rita Simmons, who is married to a failing farmer called Bill, and Irene, who is wed to the local doctor Eric Parry. Both marriages are facing a crisis. All four protagonists are superbly drawn and complex, with Miller, a novelist who deserves much wider acclaim, drawing on memories of his own time working in an asylum and his country doctor father’s troubled marriage.

Miller carefully picks apart the life of Eric, supposedly some sort of “pillar” of the community, and gradually reveals his malformed heart. There are terrific set pieces – especially the drunken Boxing Day party – and Miller reveals his gift for capturing so much about a time and a society in an offhand remark (“Consider us informed”, says a soulless man, when Irene tells fellow train passengers that she is pregnant). Miller’s deft powers of description – he refers to dying hydrangeas with “the uncut flower heads, dry as money, rattled and whispered as the wind caught them” – are scattered among explorations of bigger themes, such as the haunting power of the past, hypocrisy, desire, secrets and the hidden unhappiness of so much of family life in the postwar era.

The Land in Winter is set in a vivid moment in England’s past – television has arrived in many houses (Benny Hill’s “leering face” is mentioned); Dr Beeching is ruining the train service and the spectre of war still looms large in the background. The novel also offers telling contrasts between life in cities such as Bristol and London and life in a small West Country village. “In the city you could be hidden; in the countryside you were always seen by someone,” writes the author, who lives in Somerset.

The Land in Winter is a brilliant novel, but wrap your emotions up tight because Miller steers it expertly towards a desolate, distressing ending.

The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller is published by Sceptre on 24 October, £20

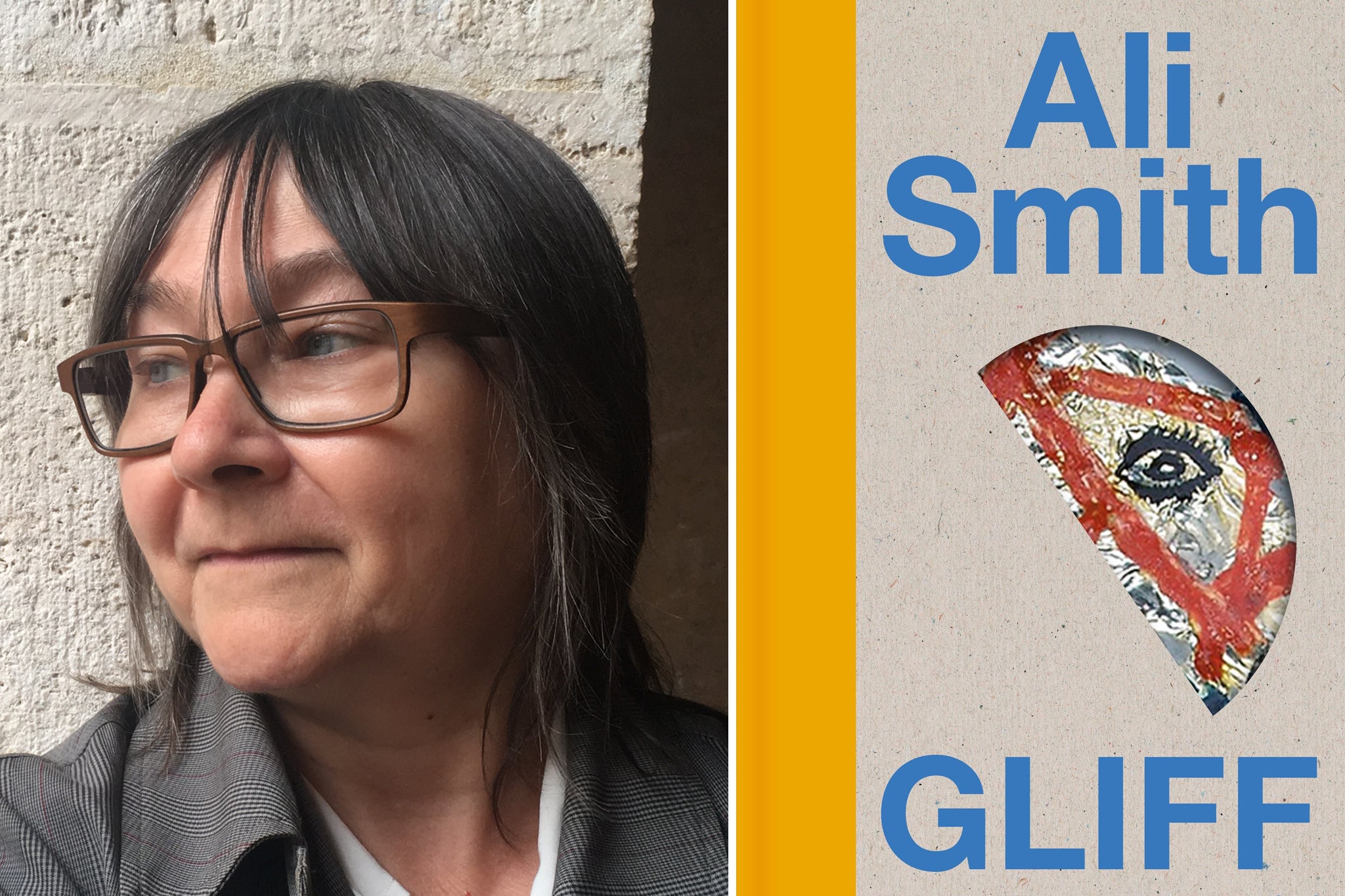

Gliff by Ali Smith ★★★★☆

Smith’s first novel since her magnificent Seasonal Quartet and Companion Piece is a (partly) dystopian novel, set in the near future, and is pretty hard to define, in truth. Gliff, which means a transient moment, a glance or sudden glimpse (and lots more besides) will be followed in 2025 by its interconnected partner book Glyph. Apparently, Glyph will tell a story that is hidden in Gliff.

Gliff is, in part, the tale of two sisters looking back at a time when they were separated from their mother. It’s also a technological cautionary tale – of people obsessed with smartphones and the ever-spreading power of AI (making versions of people Smith calls “digital splinters”). Some people in the novel are called “unverifiable”. In this brave new world, CC cameras are “shonky” on purpose (to let people “be disappeared”) and the rivers are still filthy. I’ll leave you to decide what is going on with the baby who has the head of a little horse.

As usual with Smith, the gorgeous prose will swirl in your head. Gliff is challenging and enigmatic – and a novel that possibly needs more than one reading to fully appreciate. I’m also sure that many readers will find more to fear than to be hopeful about in a novel that also reflects on what our toxic present has in store for the next generation.

Gliff by Ali Smith is published by Hamish Hamilton on 31 October, £18.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments