Alexander Armstrong: ‘People are forgiving of privilege so long as you’re not entitled or tedious’

The comedian and ‘Pointless’ presenter has written his first children’s novel. He talks to Helen Brown about borrowing from Harry Potter, finding Roald Dahl’s cruelty funny, and why he’s not worried about Richard Osman outselling him

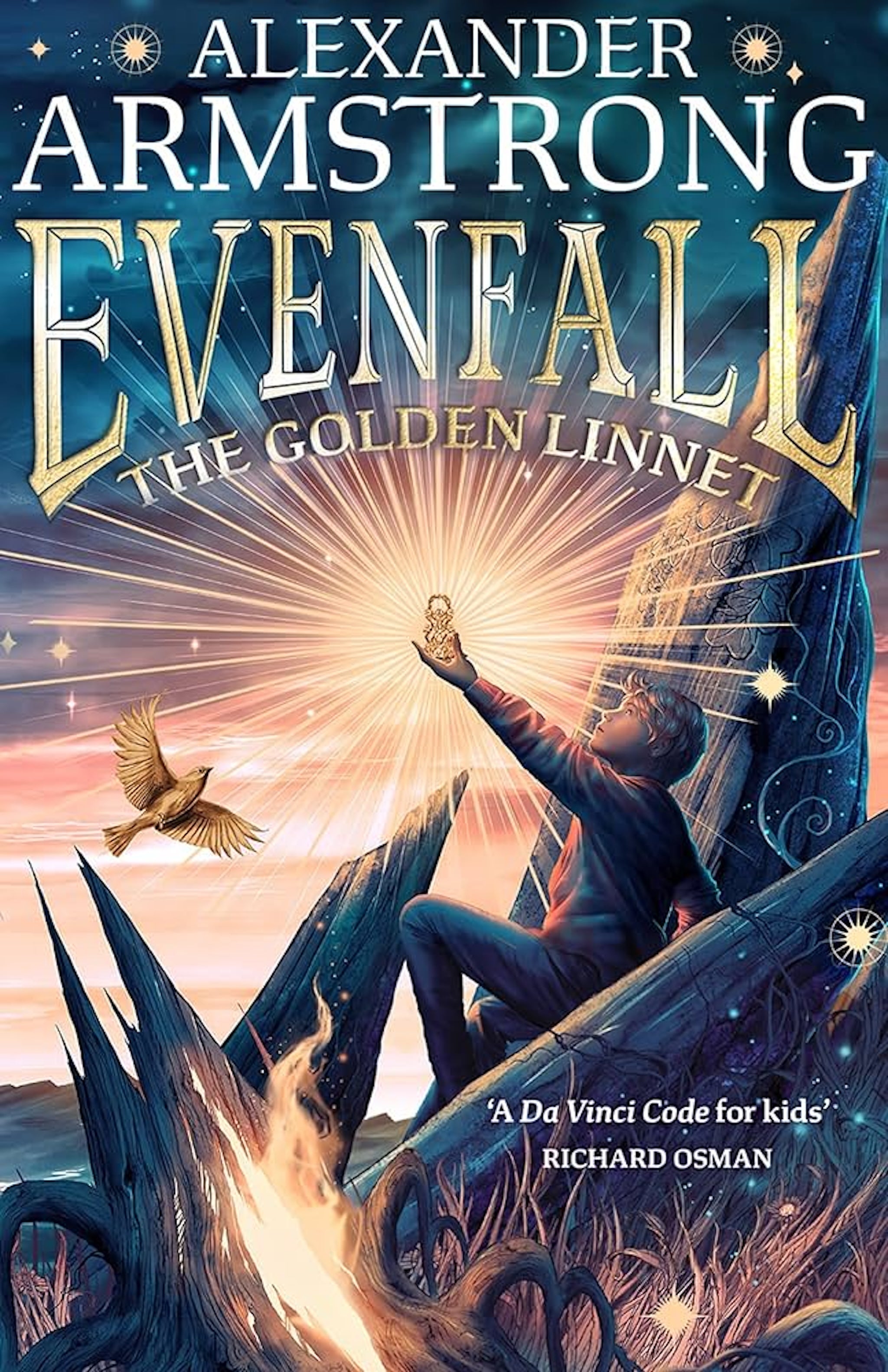

Alexander Armstrong holds his hands up. “Comedians writing children’s books? Yes, I’m another of those, I’m afraid.” So this month the quiptastic quiz show host’s first fantasy adventure – Evenfall: The Golden Linnet – will be joining the works of Davids Walliams and Baddiel, Miranda Hart, Romesh Ranganathan, Sandi Toksvig, Charlie Higson, Chris O’Dowd, Richard Ayoade, Lenny Henry and his former stand-up partner Ben Miller in the great British stand-up invasion of the children’s fiction market.

In his defence, the 54-year-old Armstrong – now best known for presenting Pointless as well as a Classic FM show – argues that “comedians ARE writers, of course”. Settling down in the “implausibly grand” hotel suite his publisher has booked for our interview, he says he’s always considered himself a “writer manque”. “I’ve been bubbling over with ideas for stories from the age of about 15,” he says. “Back then I wanted to write film scripts and the plots of family action movies, dark psychological thrillers were all buzzing away in my brain. But I’d never sat down alone for any length of time and written the bloody things… Instead I discovered that writing sketch comedy was a quick fix. An outlet for all the ideas I bottled up…”

Downplaying the very funny sketches with which he and Miller made their names in the late 1990s as “quick fixes” is one of many self-deprecating comments Armstrong makes today. Later he’ll tell me anecdotes about his terrible memory, his celebrity gaffes and some public shaming over the misdemeanours of his two Norfolk terriers (Dotty and Haggis). As a posh, white, male Cambridge graduate with a solid BBC gig such affable humility seems like a wise and ingrained attitude. “People are forgiving of most backgrounds so long as you’re not entitled or tedious, I think…” he shrugs.

Back in the day he was a little more arch and edgy, if just as silly. Armstrong and Miller both owned and winked at their privilege, calling the production company they formed in 2007 (and dissolved last year) “Toff Media”. Like peers Mitchell and Webb, the duo specialised in sarky, self-aware, meta-comedy that made hay with establishment-skewering anachronisms: the pianist at a formal Victorian soirée breaking into a burst of Electric Six’s hit “Gay Bar”; Stone Agers critiquing each other’s cave paintings; RAF airmen talking in youth vernacular with vintage Noel Cowardesque accents: “Spies are like, so fake”, “Hitler was well vex”, “That’s against the Geneva Convention an’ shit”.

One 2007 sketch saw him spoofing the BBC’s genealogy show Who Do You Think You Are? – with Armstrong horrified to turn up a heritage of poverty, prostitution and paedophilia. Appearing on the show for real in 2010, the Northumberland-born doctor’s son traced his family back from the “fringes of the aristocracy” all the way through the court of King Charles II to learn he’s the 27x great grandson of William the Conqueror.

Today he lights up at the memory of making that show, still boggling at the “extraordinary connection and loyalty you can feel to ancestors you’d never even heard of two days earlier, to people who are frankly nothing to do with you. In my case, I became furious on behalf of some great-great-great-grandfather who was done over by his older brother… the genetic link just really hooks you in.” A pause. “It’s like having a camera stuck up your bum. You’re going quite deep into yourself and yet these are people you don’t know and can’t be responsible for.”

Sam, the 12-year-old hero of Evenfall, also finds he has an extraordinary heritage. It turns out he’s connected to a magical society of storytellers, The Order of the Evening, and develops a strange superpower that allows him to swoop out of his body – stuck at home with his mentally unwell father – to slingshot his spirit into the wild landscape of the North East.

Armstrong is a firm believer in the “spirit of place” and feels most connected to the “rugged benevolence” of Northumberland. “I can see precisely why the early Christians were inspired to settle down there, although it has a pagan power too,” he mulls before describing growing up “on the edge of a moor” in a town called Rothbury where another distant ancestor – industrialist and inventor Sir William Armstrong – built the “fairy palace” of Cragside, a country house and hunting lodge (now owned by the National Trust).

“Safe to say I was a curious child,” he concedes. “I spent a lot of time in my own head.” He relished the gothic horrors of vintage fairy tales, such as those of the Brothers Grimm and other European writers, “which could be very dark in places but very magical. I was fascinated by Struwwelpeter, with its gruesome stories of what happened to naughty kids. The character who got his thumbs chopped off and the other boy, Johnny-Look-In-The-Air, who starts to drown. There was an illustration showing him getting swept into this water system, just floating along…” He shakes his head. “My sister took it out of the book case and hid it because she hated it so much.” He speculates that his delight in these horrors “might have been a boy thing? I also roared with laughter at some of the crueller moments in Roald Dahl books…”

He’s mended his ways, it seems. On the controversy around whether the more offensive words in Dahl’s books should be amended or cancelled, Armstrong says that “while it’s tempting to get huffy about texts being changed”, he’d much prefer to see a few words altered than “for teachers to feel they can’t put such good books in front of kids any more”.

Maybe we could put it down to Armstrong’s love of high drama rather than his gender. He admits that he’s only turned down Strictly because he “can’t give up his weekends with the family at home in Oxfordshire” and “not because I’m avoiding the fake tan and sequins – I’d be up for all of that!”

Those who saw Armstrong’s resonant turn as Chicken Caesar on The Masked Singer (Davina McCall thought he was Robbie Williams) will know he’s a confident bass baritone singer. In fact he released three albums of popular classics between 2015-17. Today he tells me his earliest obsession was music. “I used to wake up very early, before anybody else was up and go and play all the forbidden records in my parents’ collection…” Forbidden? Wild, corrupting rock ’n’ roll stuff? “Ha. No. All the Beethoven and Mahler symphonies, oooh, and Verdi overtures. Mmmm!” Through his Classic FM show, Armstrong wants to connect listeners with that same early, uninformed thrill he felt at the turntable. He has no truck with “the snobbery that has built up around classical music and mostly comes from people who don’t actually know that much about it themselves”. He teases he’ll be launching a venture next year called “Curved Music” designed to bring classical music into “new spaces”.

I roared with laughter at some of the crueller moments in Roald Dahl books

From the age of 11-13 he attended St Mary’s Music School in Edinburgh which he says was run in the building of “a former sanatorium at the end of the poshest street in Edinburgh, called Belgrave Crescent. It was the last house on the road next to all these frightfully aristocratic Scots. We were a bunch of unruly musicians, running around pretending we were the kids from [Eighties TV show] Fame. Without the legwarmers, alas.” It was in Edinburgh that Armstrong had one of the “thrilling childhood experiences” that he’s transposed onto the hero of his book.

“It’s quite hard to explain,” he recalls. “But I remember just sitting and staring out of the window at the view on an early summer evening and feeling this sense of golden happiness and I found it extremely exciting. I felt a sort of inner equilibrium with a fizz of excitement. I sat there for at least an hour, which is a long time at that age, isn’t it?” He shakes his head like a kid still coming out of a trance. “I like to think we all have those strange “superpower” moments as children, if we have the time and space to seek them out. I kept that experience at the back of my mind and it came out in the scene where Sam is pressing his forehead against the window and sending his spirit out into the rain…”

Armstrong’s voice was his real superpower at that age, though. He scored music scholarships to Durham School then Trinity College, Cambridge where he studied English. Sketch show fans will have seen him play the piano; he also played the cello but swapped it for the “much more masculine” oboe. Although he joined the Footlights in his final year he didn’t meet the slightly older Miller – “the dearest fellow” – until moving to London. The duo performed their first Fringe show in 1994 and had their first TV series commissioned by Channel 4 three years later, moving to BBC One in 2007.

In 2009, Armstrong began hosting the quiz show Pointless, created by a group at Endemol including Richard Osman (whom Armstrong met at Cambridge). According to Osman, the show was conceived as a “reverse Family Fortunes... rewarding obscure knowledge, while allowing people to also give obvious answers... a quiz which could be sort of highbrow and populist simultaneously”. But the unexpected USP was the quirky relationship between the co-hosts, Armstrong and Osman. An early Guardian reviewer relished watching “their slightly bizarre relationship evolve, like two men victim of a misjudged seating plan at a particularly bland dinner party, forced to make small talk and constantly trying to outdo each other in the ‘dad joke’ stakes”.

Does Armstrong feel most comfortable as one half of a double act? He nods. “It’s the coward’s way into writing. You have somebody to prop you up and you have two sets of shoulders to bear the ignominy if it goes badly.” He says that “almost everything I’ve done has been a collaboration and I’ve been good at picking people who are much better than me at it. Maybe that’s my genius, my greatest skill!”

So he doesn’t mind being eclipsed by backroom boy turned bestselling author Richard Osman? He laughs. “Not at all! Richard has towered over me in every way since we were 18, so I’ve had a long time to make my peace with the fact that he’s annoyingly successful and clever.” Far from stoking rivalry, Armstrong says that hosting Pointless has forced him to “revise my opinion of the general populace, because the contestants who appear on the show are just lovely. I’ve gone from fearing we’re all doomed and everybody is at each other’s throats to having my faith in humanity restored”.

This explains the way Evenfall zones in on the importance of community and people sharing stories without tech. “In my fictional world it’s storytellers who run the world, not an illuminati, a strange cabal of squillionaires. I think that’s true in the real world too. All religions are stories, aren’t they? It’s stories that inspire people to live or give up their lives… they teach us about the joy of spending time with other people and I would love there to be a revival in people hanging out,” sighs Armstrong. “People going to pubs again. The sorts of things that have tailed off because we retreated into our phones.” His hero Sam doesn’t own a mobile phone and manages to evade the shadowy villains bent on his destruction until his friends start pulling their own phones out of their pockets. “It’s the phones that put them in danger,” he warns.

As the father of four sons aged 17, 15, 14 and 9, Armstrong knows all about the distractions that phones can prove. He himself is a sucker for “reading the news, and then the ‘breaking news’ even when that turns out to be not real ‘breaking news’ but the details of some new steel tariff in Montenegro”.

But he’s loved reading to all four boys and tells me he’s now on his fourth cycle of reading the Harry Potter books. “I also read them myself – I’m not ashamed to say I hurled myself into those books.” Reading them aloud made him realise that Rowling’s boy wizard had influenced his own fiction. “I realised I’d given Sam a cow lick and green eyes, like Harry,” he winces. And where Harry has a lightning bolt on his forehead… “Sam has one on his family seal! I know! If JK Rowling finds out what I’ve done I hope she takes it for the loving homage it is!”

Like the Potter books, Evenfall is overshadowed by a truly malevolent villain whose identity remains vague at first. “I think baddies should be allowed to be BAD,” says Armstrong, earnestly. “We shouldn’t be so careful to avoid offence that we fail to give children the tools to understand human nature. Though those Victorian fairy tales were gruesome, they do teach you what virtue, dishonour, compassion and forgiveness look like.” He argues that “stories should sharpen the perception and give young readers the tools to spot when somebody like Donald Trump is talking utter horses***”.

Armstrong grins and leans back in his hotel chair, channelling a little Bond villain himself. “Both the baddies in my book meet unpleasant ends and I punched the air when they bit the dust. Mooo-haaaa-hah-hah-hah.”

‘Evenfall: The Golden Linnet’ is published by HarperCollins on 12 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments