Books of the month: From Day by Michael Cunningham to The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez

Martin Chilton reviews the biggest new books for January

The present Tory obsession over immigration is nothing new. At the end of Winston Churchill’s time as prime minister in the mid-1950s, according to Walter Reid’s Fighting Retreat: Churchill and India (Hurst), there were “13 separate cabinet discussions on the matter of colonial immigration” in a single year.

Reid seeks to answer the question, “Why was Churchill so vindictive towards India and Indians?” The historian is adamant that Churchill “must be judged by the values and attitudes of his time” and contextualises numerous controversies around the man who led the fight against Hitler. It’s hard to believe, however, that any progressive young readers (if they could care less about Churchill anyway) would not simply be appalled by a bloated bigot who disparaged other races in the vilest terms and wanted “Keep Britain White” to be the slogan of the 1955 Conservative Party.

Egypt’s The Great Pyramid, the only one of the Seven Wonders that survives virtually intact, reminds us of the overwhelming human desire to collaborate and create “beyond the possibilities of the individual,” states Bettany Hughes in her rich historical study The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World (Weidenfeld & Nicolson). I particularly enjoyed the chapter on The Hanging Gardens of Babylon and learned that “paradise” comes from the Persian word for a beautiful walled garden.

Maeve Brennan’s delightful essays for the New Yorker, published between 1954 and 1981, are republished in The Long-Winded Lady (Peninsula Press). Dublin-born short story writer Brennan, who died in 1994, was an astute observer of day-to-day life in New York. She dissected the foibles of people, especially the “small rather glum men” who populated the transport system. I loved her 1954 essay “Painful Choice”, which captures the moral dilemmas of everyday life in an entry less than a page long. Splendid.

Finally, a recommendation for Orla Owen’s humorous novel Christ on a Bike (Bluemoose), in which a woman called Cerys receives an unexpected inheritance – with strange rules attached. Owen has some sharp things to say about moving to a rural village and there is a lighthearted description of Cerys learning to cope with driving through narrow lanes full of low-hanging branches. “She was breathing in and squeezing her shoulders up as if that would make her smaller, less likely to scrape the edges of the car,” Owen writes. Yep, I know the feeling.

Non-fiction books about the moon, and Volodymyr Zelensky, along with fiction by Sigrid Nunez and Michael Cunningham and debut novels by Kate Brody and Ferdia Lennon, are reviewed in full below.

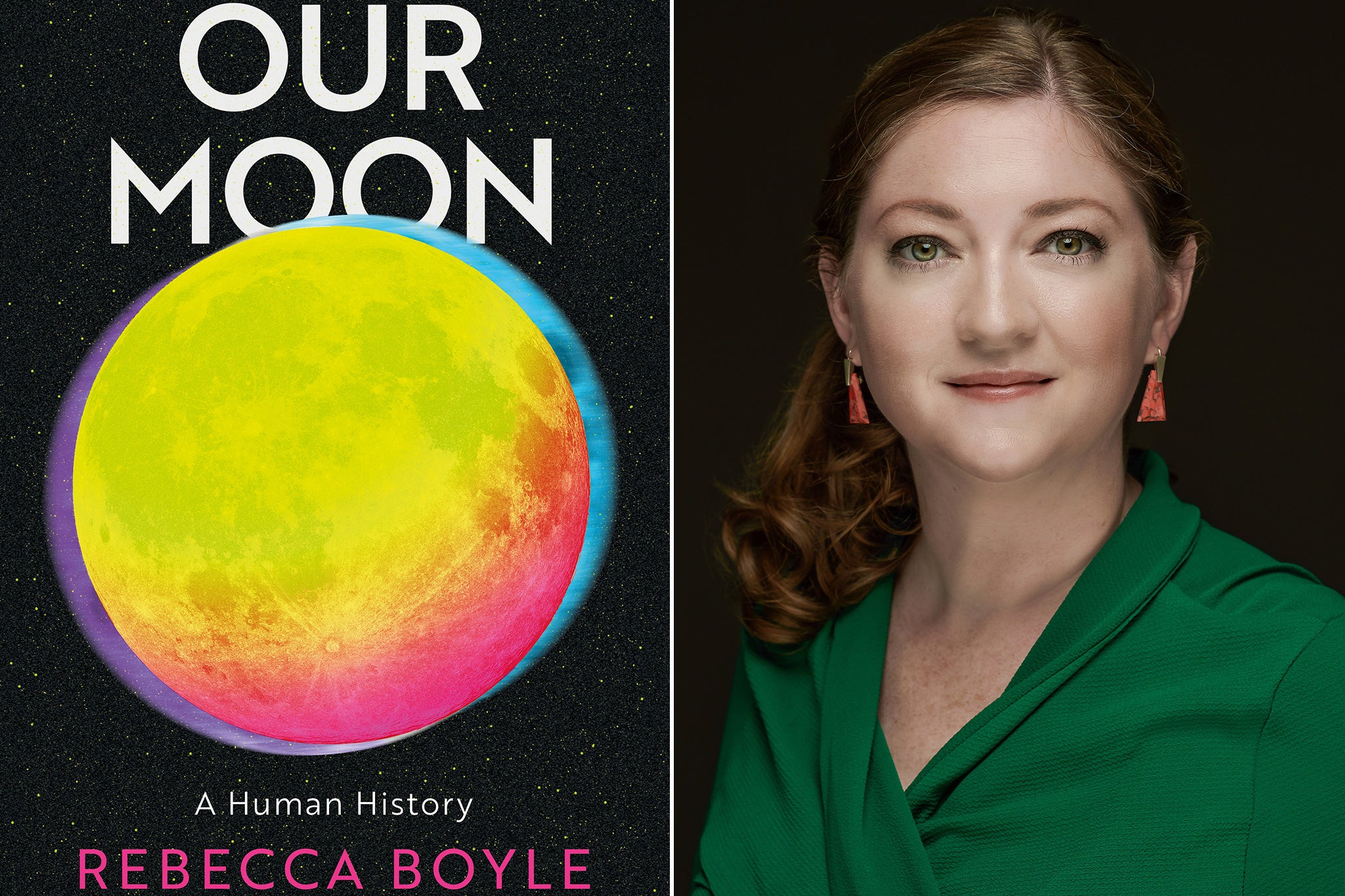

Our Moon: A Human History by Rebecca Boyle ★★★★☆

When novelist Christopher Isherwood was making a living as Hollywood scriptwriter for MGM in the 1930s, he wrote a line into the 1941 Ingrid Bergman thriller Rage In Heaven that said: “The Moon. It’s staring at me, like a great eye.”

As someone who enjoys staring back at the Moon and pondering on its mysteries, I was surprised to learn from Rebecca Boyle’s Our Moon: A Human History that its landscape is full of rich colours, including milk chocolate browns, yellows, golds, rosy pinks and even purples (there is volcanic glass in every colour of the spectrum on the Moon). She also explains why there is no sound at all on the Moon, and why it smells like fireworks that have just gone off.

Boyle, a Knight Science Journalism Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, divides her book into three sections, including “How the Moon was Made”. There is new information coming out all the time, but it seems the Moon was formed when a planet called Theia, about the size of Mars, smashed into earth. The Moon, which was once liquid magma, was a product of this collision.

Our Moon skilfully combines science, anecdote and philosophy. I mused afterwards about the poor Russian tortoises sent out into space in 1968 with no food or drink. They were the first creatures from here to journey beyond Earth’s orbit and are now largely forgotten, in part because they weren’t even given names (“the Soviets referred to them, rather coldly, as ‘the experimental animals’,” notes Boyle). The author also deals with the growing knowledge about the Moon discovered by 21st-century scientists, which includes recent studies on how the phases of the Moon do indeed influence patients with bipolar disorder.

Boyle also deals with the future. In 2019, China landed a small robot called Chang’e 4 on the Moon’s far side, the first time such a feat has been achieved. She raises a concern that China’s real plan is to use the Moon for mining.

This engrossing book tells us so much about the Moon and space exploration, but it also encourages readers to ponder on our planet and our insignificant place in the universe. As Boyle poetically notes, “The Earth is so fragile, so cosmically small, so completely isolated and precious and limited. Earth is all we’ve got.” And we also have the Moon to gaze up at and write songs and poems about.

Our Moon: A Human History by Rebecca Boyle is published by Sceptre on 18 January, £22

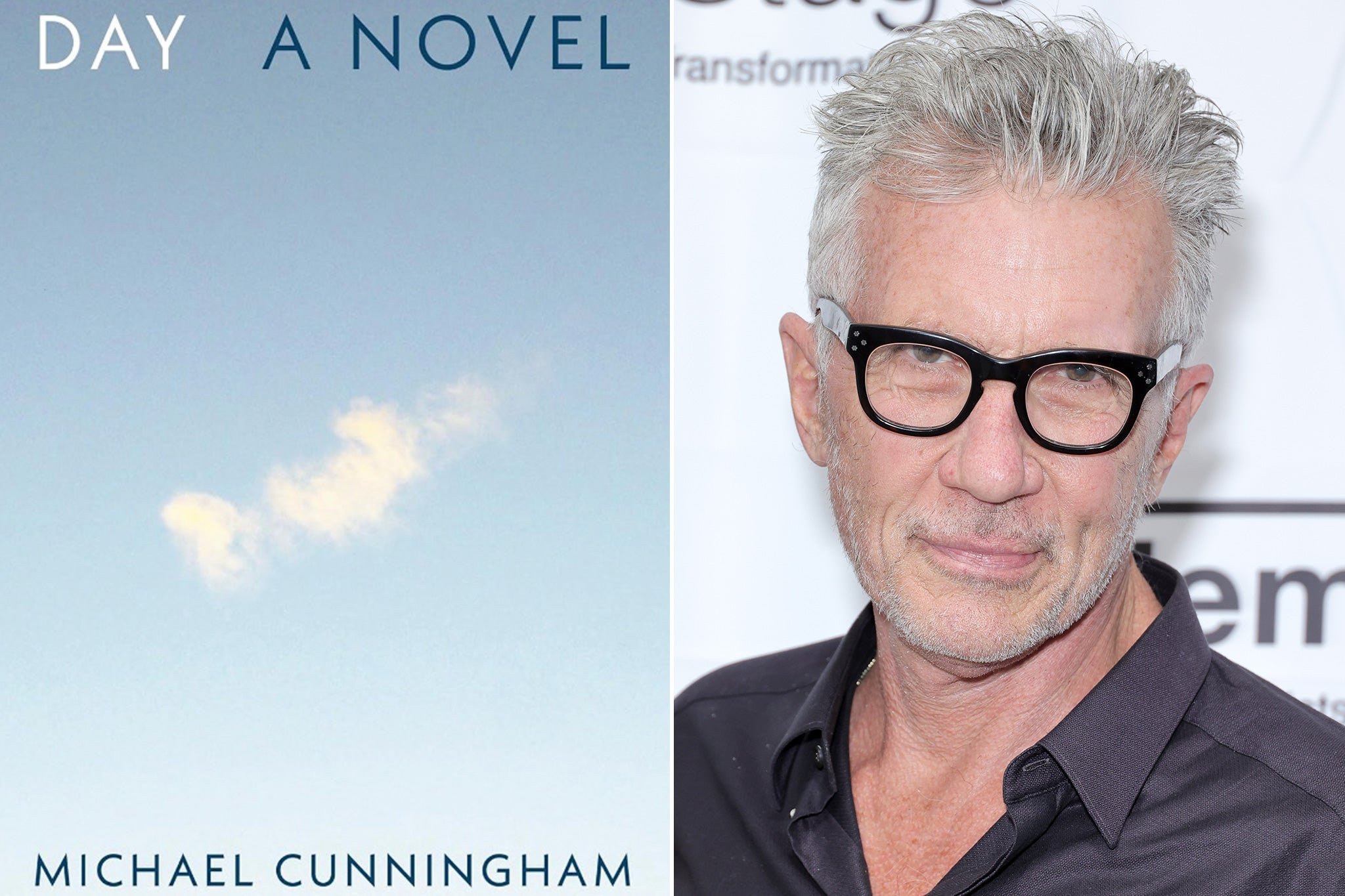

Day by Michael Cunningham ★★★★☆

I was struck recently by Michael Cunningham’s answer to the question “what is your greatest fear?’” The Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Hours replied: “The fact that, until recently, ‘the end of the world’ would have seemed pretentious and evasive, and now seems like the only possible answer.”

Cunningham, who turned 71 in November, explores the global pandemic in Day, his first novel since 2014’s The Snow Queen, and although I don’t recall the words pandemic, Covid or coronavirus appearing in the novel, the effects of the virus on a New York family is at the heart of his deeply affecting new story.

Day unfolds in three acts, each on a single April day over 2019 (morning), 2020 (midday) and 2021 (evening). The main characters are Isabel, who works at a magazine, and her husband Dan, a failed rock singer and their two children, along with Isabel’s brother, Robbie, a teacher who is secretly in love with Dan.

Any parent will flinch at the scene in which six-year-old Violet leaves a note asking her parents to remember to shut the windows, which they understand reflects her terror that the virus will float in through them. The finale, which is set in a run-down country house in the quarantine era, forces the family to confront grief and loss. Cunningham has written a tender, painful portrayal of the theme of connection and disconnection. Day, a haunting novel about a terrible time, has important things to say about how we must learn to live together – and apart.

Day by Michael Cunningham is published by 4th Estate on 18 January, £16.99

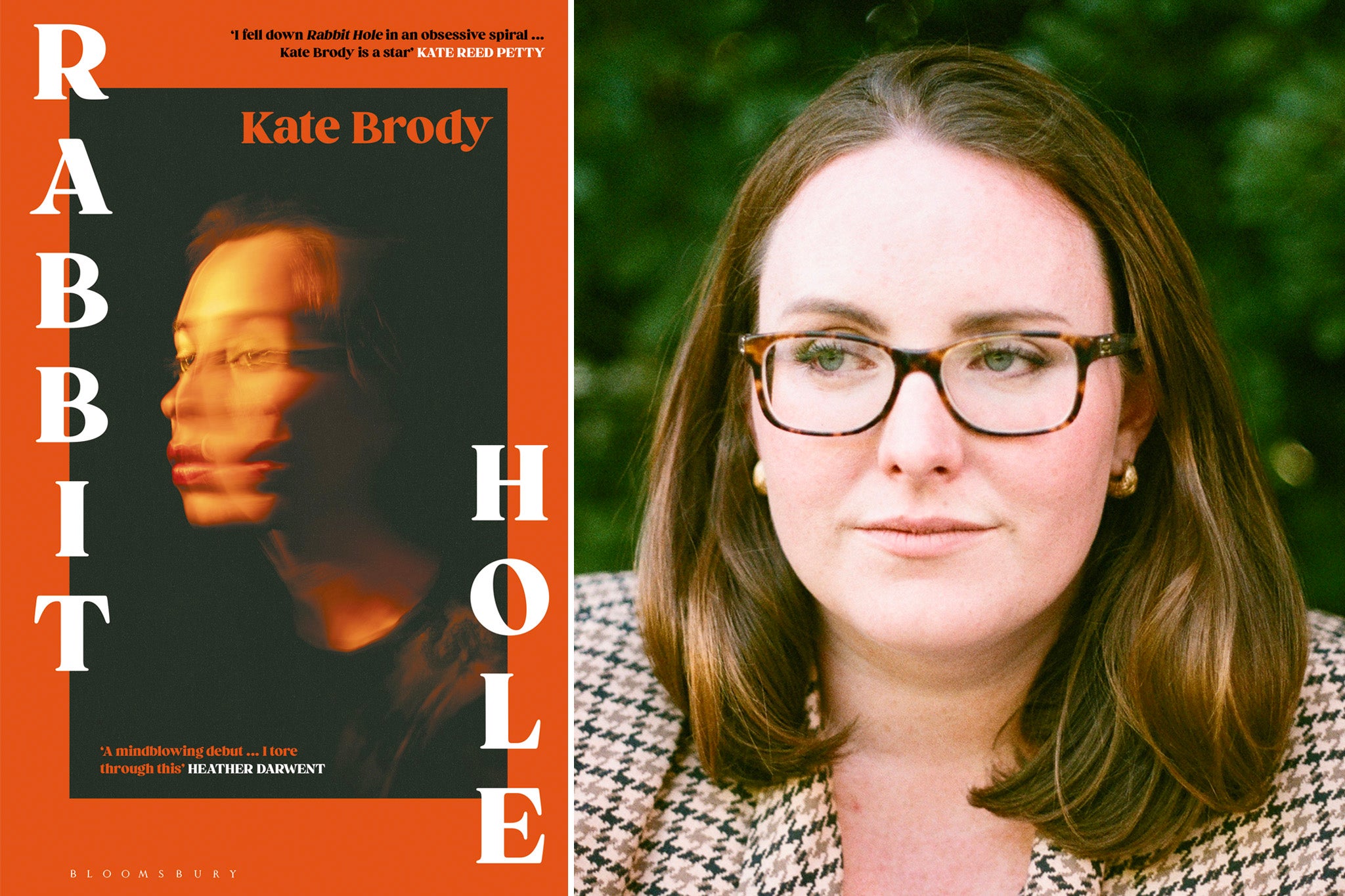

Rabbit Hole by Kate Brody ★★★☆☆

The numerous popular podcasts about murders and comedy television dramas such as Only Murders in the Building – starring Steve Martin, Martin Short and Selena Gomez – are all reflective of modern society’s obsession with true crime.

Kate Brody’s debut novel Rabbit Hole, in which high school English teacher Theodora “Teddy” Angstrom hunts for the truth about her sister’s disappearance, has some telling things to say about the voyeuristic and entitled nature of fetishistic true crime fans.

Teddy was 16 when her older sister, Angie, disappeared after sneaking out to a party – and her father’s suicide (which opens the book) sparks her own sleuthing into an event a decade old. Propelled by new clues and Reddit conspiracy theories, Teddy gets involved with a cast of strange people and her paranoia begins to spiral. Despite occasional loose moments, Rabbit Hole is a twisty, pacy crime thriller with wit and unusual plotlines.

Rabbit Hole by Kate Brody is published by Bloomsbury on18 January, £16.99

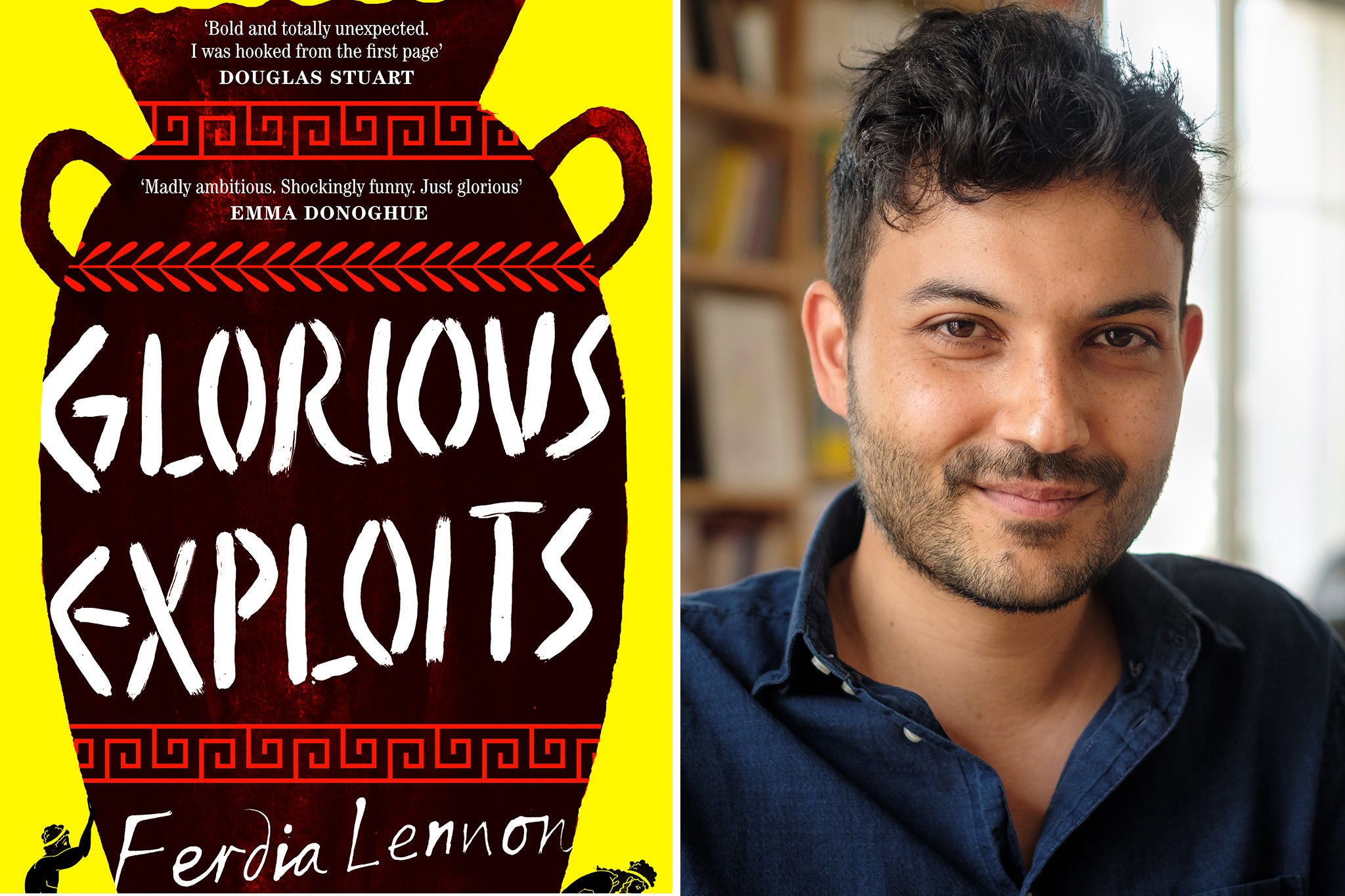

Glorious Exploits by Ferdia Lennon ★★★☆☆

Setting your debut novel in the quarries of Syracuse in 412BC is a challenging move and one that Irish-born Ferdia Lennon, a graduate of History and Classical studies from University College Dublin, pulls off. Lennon says he believes that history is a “dialogue of competing stories and interpretations” and through his main characters Lampo and Gelon, two local potters, he explores what life was like in Sicily after the failed invasion by Athens. Thousands of Athenian soldiers are held captive in the quarries of Syracuse – but some of them, for scraps of bread and a few olives, will recite lines from the plays of Euripides. This sparks the idea in Lampo and Gelon to put on a version of Medea.

The dialogue is spiky and rude and the humour – including producing the sound of a “sick bird” when you try to play the aulo “blowing into that f***er with everything you’ve got” – is genial and wry. Glorious Exploits is a bold, witty debut that explores the nature of art, friendship, culture and the risks of daring to dream.

Glorious Exploits by Ferdia Lennon is published by Fig Tree on 18 January, £16.99

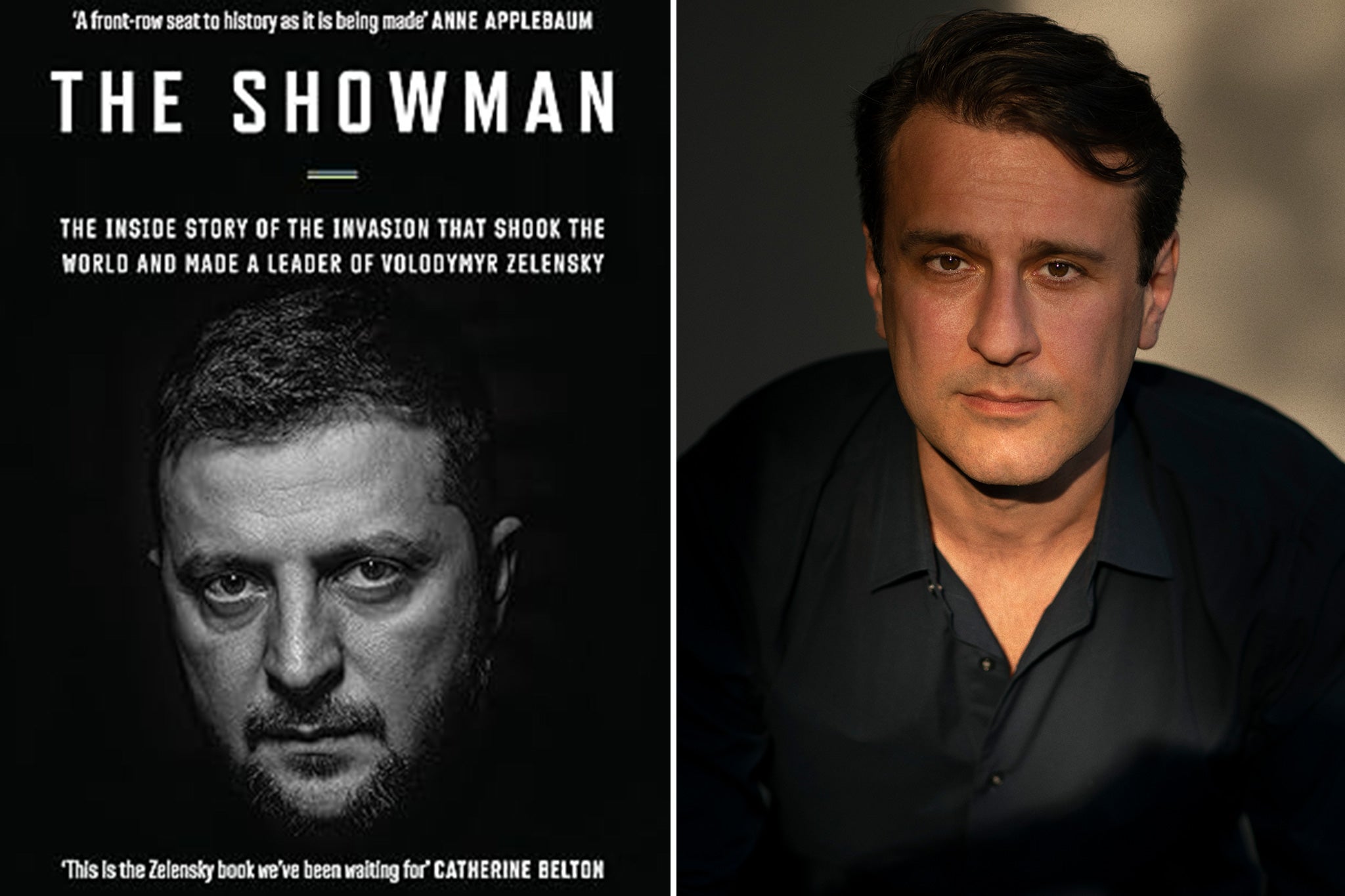

The Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr Zelensky ★★★☆☆

When Volodymyr Zelensky was a teenage heartthrob with a raspy voice and skin-tight leather pants, he started doing comedy. He became, according to Time journalist Simon Shuster, “addicted to the applause, the adulation” of being in front of a crowd.

In The Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr Zelensky, Shuster makes clear how essential Zelensky’s “instincts as an actor” and understanding of publicity and keeping Ukraine in the spotlight have been in the war against Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

The Showman is a compelling piece of living history and Shuster, who has reported from Russia and Ukraine for the best part of two decades, skilfully pieces together the transformation of Zelensky from a maverick who railed against politicians as “mother****ers who steal and talk s***” to a statesperson capable of winning over world leaders.

The inside information in the book about the events since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 is intriguing and you get a glimpse of Zelensky’s personality – he eats fried eggs every morning in his bunker and sends his commanders thumbs-up emojis – and overall it is hard not to admire his courage and even reckless bravery. It’s also moving to read an inside account of the effect of Russia’s invasion on his wife Olena, teenage daughter Oleksandra and young son Kyrylo. The family had to go on into hiding in Ukraine, evading Russian kidnappers and potential assassins, and we are told that Kyrylo, then only nine, started drawing disturbing images of war carnage.

There are also insights into the chaotic nature of Putin’s invasion plans. Early in the conflict, Russian paratroopers parachuted into areas near Kyiv that were marked as a forested region. They were using maps printed in 1989 and the areas had since been urbanised. “They had nowhere to hide and the Ukrainians cut them down with machine-gun fire and artillery,” writes Shuster.

Although the book is complimentary about Zelensky, it also presents a complex picture of a sometimes flawed, egotistical man, who was not averse to his own compromises when it came to money, earning enough from his Russian-based television and movie production company to need tax havens in Cyprus to stash his wealth.

Perhaps the most poignant anecdote in this highly readable book is about Zelensky’s one face-to-face meeting with Putin, in December 2019, when the Russian leader was “irritable and impatient”. Zelensky thought he could charm Putin, as he did most people. However, as Zelensky’s aide Iryna told Shuster, the former comedian and actor completely failed to understand the lack of “humanity” that is at the core of the Russian president.

The story – the war – is still in progress, of course, and most of the world is left hoping that the man who wrote a ballad in 2014 called “We’ve Told Russia to Get F***ed” will continue to defy Putin.

The Showman: Inside the Invasion that Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr Zelensky is published by William Collins on 23 January, £22

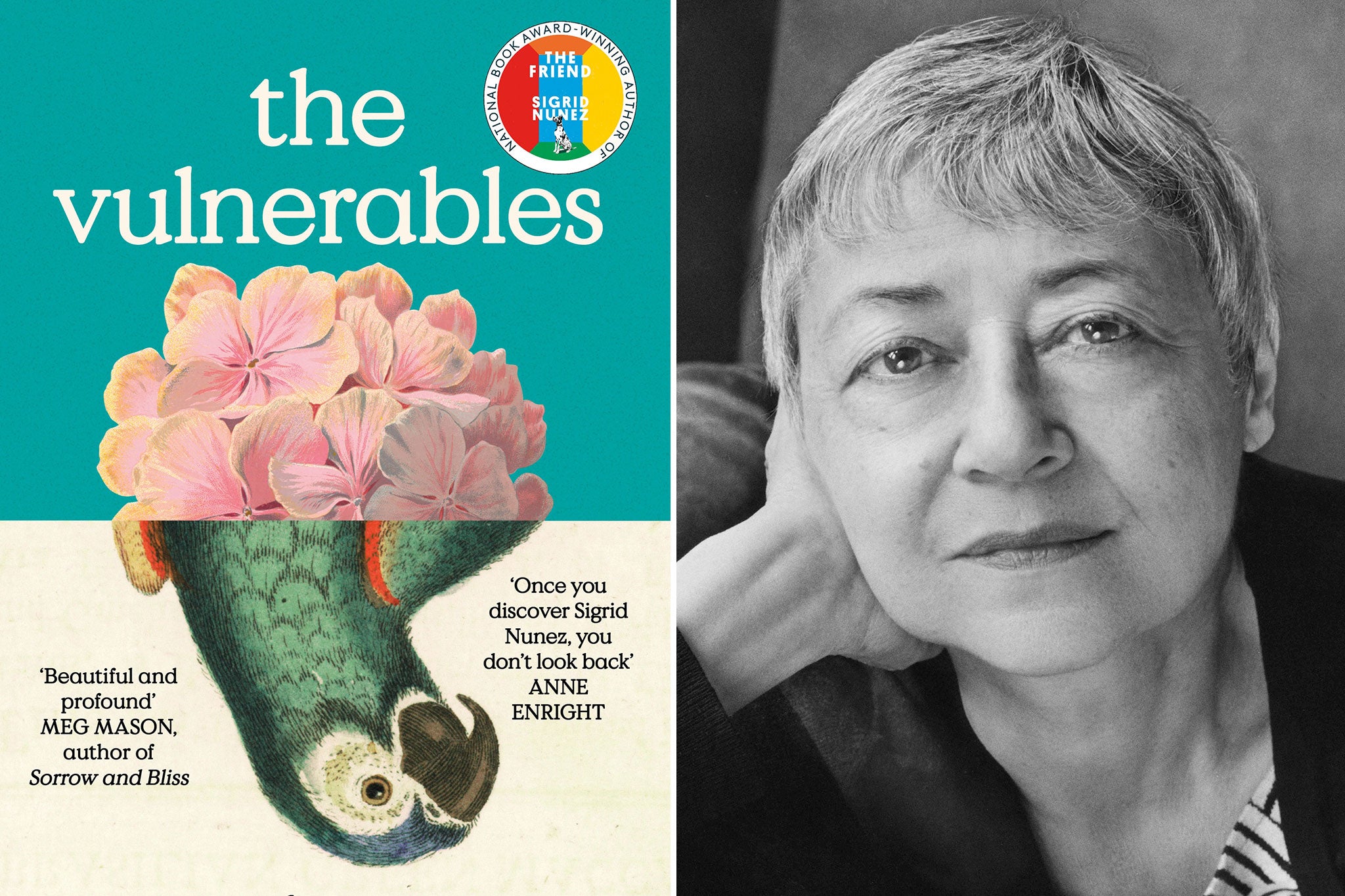

The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez ★★★★★

Sigrid Nunez, who was 67 when she won the National Book Award for The Friend (2018), is among the most interesting writers of our generation. Her latest novel – as with The Friend and What Are You Going Through (2020) – is narrated by an ageing woman who, like Nunez, lives in New York City and works as a professor of writing.

The Vulnerables is set in the early bewildering days of the pandemic and is about an unnamed protagonist who is thrown together in a Manhattan apartment with a college drop-out and an eccentric parrot called Eureka.

The meandering, almost essay-like prose allows Nunez to explore her characters and the fears of living in a stricken world with all its systems collapsing. There is an unsettling scene in which a vindictive stranger on a bike, a man wearing a balaclava, deliberately coughs into the old woman’s face.

Nunez is both as cold as ice about ageing (the old are “bleached and bent and shrivelled”) and funny (“you reach a certain age, and it all kicks in: Social Security, Medicare and a fondness for hydrangeas”) and constantly surprises you with her references (Larry David, Lily Tomlin) as well as her anecdotes (it’s tough to forget the startling image of a young woman with an eating disorder who kills her appetite by coating her tongue with Tiger Balm).

Nunez’s novel is also deeply concerned with what it means to be a writer and The Vulnerables, including in a whole section called “Interlude”, features some thoroughly enjoyable nuggets of wisdom from other authors, including Edna O’Brien and Anton Chekhov. Nunez reminds readers about the deep sexual weirdness of Proust and her protagonist also reflects on how boring she found Dickens’s late novel Our Mutual Friend, giving me flashbacks to the drudgery of studying that 900-page novel long ago in A-Level days. Nunez later includes a sharp quip from a critic that “in almost every long book I read I see a short one shirking its job”.

The Vulnerables is an enriching and thoroughly enjoyable read, delivered by a superb writer who knows all too well how vulnerable all lives are.

The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez is published by Virago on 25 January, £16.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments