Books of the month: From It’s a Wonderful Life by Michael Newton to The Small States Club by Armen Sarkissian

Martin Chilton reviews the biggest new books for December

“Today’s Christmas cake is itself a kind of ghost of Christmas past, a shrunken imitation of the behemoths of olden times,” writes Andrew Baker, publishing editor of the Telegraph, in his chapter on the festive food staple and its strange, riotous past as the so-called “Twelfth Cake”. The background, with a recipe to boot, appears in the Yuletide section of Baker’s entertaining, highly convivial Cake: A Slice of British Life (Mudlark), which also includes a chapter on birthday cakes and the origins of Colin the Caterpillar. Yum.

Cookery books make for wonderful presents and my pick from an impressive 2023 includes Julius Roberts’s The Farm Table (Ebury Press), a heartwarming collection of recipes based on food grown at his small farm. Another highly personal, wonderful publication is the new edition of Sarah Raven’s Garden Cookbook (Bloomsbury). Two European-centred recipe books I relished were Helena and Vikki Moursellas’s exuberant Peinao: A Greek Feast for All (Smith Street Books), and Manon Lagreve’s elegant debut book Et Voila!: A Simple French Baking Love Story (OH Editions).

Another knockout is Imad Alarnab’s Imad’s Syrian Kitchen: A Love Letter from Damascus to London (HQ). For home-cooked curries, I would recommend Chetna Makan’s Chetna’s Indian Feasts: Everyday Meals & Easy Entertaining (Hamlyn) and Maunika Gowardhan’s Tandoori Home Cooking (Hardie Grant Books), while two excellent all-round books are Ravneet Gill’s Baking for Pleasure: Comforting Recipes to Bring You Joy (Pavilion) and Sabrina Ghayour’s Flavour (Aster). For a complete vegetarian focus, I would suggest Mildred’s Easy Vegan (Hamlyn) and for a go-to, easy-to-follow guide (especially for a non-cook like me), there are many manageable, highly tasty meals in Rick Stein’s Simple Suppers (BBC Books).

If classic fiction is your thing, then a suggested gift is Joseph Heller’s crazily funny novel Catch-22, which still has so much to say about a wartime world that has lost its mind. A beautiful new edition, with cloth quarter binding, contemporary illustration and silk ribbon, is part of The Vintage Quarterbound Classics series that came out this autumn. Vintage’s series also includes Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle, re-released on the 75th anniversary of the book’s first publication.

Finally, a suggestion for younger readers. I was one of those children who is a visual learner and there is so much brilliant content in Britannica’s Encyclopedia Infographica (What on Earth Publishing), which is packed with fascinating information about space, Earth, animals, humans and technology, told through engaging images. The 200 infographics are by Valentina D’Efilippo and the accessible, informative words are courtesy of Andrew Pettie and Conrad Quilty-Harper. One to keep kids happily occupied away from screens.

Books on the Christmas movie classic It’s a Wonderful Life, the works of Chaucer, non-fiction about American warfare, gulags, small states and a prison memoir by Keri Blakinger are reviewed in full below. Season’s greetings!

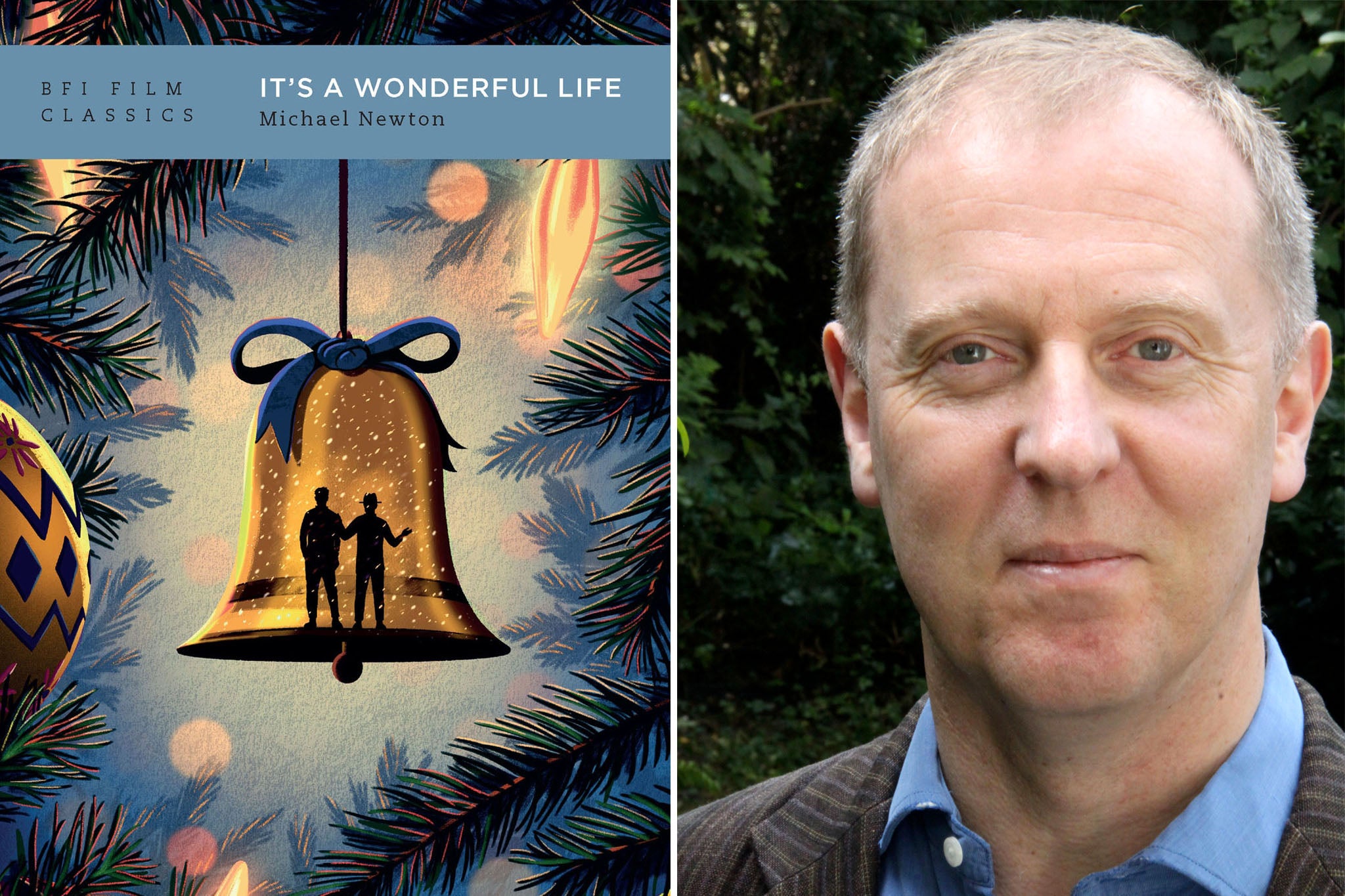

It’s a Wonderful Life by Michael Newton ★★★★☆

If the words “Merry Christmas, you wonderful old Building and Loan” are ingrained in your Christmas habits, then you’ll get a lot out of Michael Newton’s It’s a Wonderful Life, which is part of the British Film Institute Classics series. Although the book came out in the autumn, it is perfect reading for this month of year.

Newton, lecturer in English at Holland’s Leiden University, tells the full story of the making of the 1946 movie, which began in 1938 as a story by Philip Van Doren Stern called The Greatest Gift. The tale eventually reached director Frank Capra, whose initial enthusiasm turned into qualms about the movie adaptation. He supposedly thought to himself midway through his pitch to the studio that he was trying to sell “the lousiest piece of s*** I’ve ever heard”.

Capra was a weird, troubled man. His father, an orange picker, died in an outrageously horrible fashion, sliced in half by a mechanical saw when Capra was a child. The filmmaker’s social and political views were a hotchpotch. He was a liberal who admired Mussolini and was rumoured to have a painting of him on his bedroom wall.

The background to the film of George Bailey and his possible suicidal day in Bedford Falls is told in interesting detail, including the constant battles between Capra and the screenwriters and other movie executives. The book is full of quirky facts: that witty author Dorothy Parker contributed some of the final lines for the vampish Violet Bick; that James Stewart, who plays hero George, was traumatised by his recent war experiences; and that there were plans to cast Vincent Price instead of Lionel Barrymore for the role of Scrooge-like Henry Potter. The book also says that the marvellous comedian WC Fields was mooted as Uncle Billy, and that jazz pianist Meade Lux Lewis, the musician who helped create boogie‐woogie, was the uncredited keyboard player in the scene in Nick’s Bar.

One final note. For anyone needing any extra reasons to be repulsed by Michael Gove, they are provided by a small segment in the book that discusses the politician’s intense dislike of It’s a Wonderful Life. Gove, who now carries the incongruous job title of Secretary of State for Levelling Up, is quoted in the book as saying he believes that the “real hero” of the movie should be the avaricious Potter, because of his “frontier spirit”. Could it be that it takes a “scurvy little spider” to know one?

‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ by Michael Newton is published by Bloomsbury Academic, £12.99

Precision: A History of American warfare by James Patton Rogers ★★★☆☆

In Precision, James Patton Rogers, who is a professor in war studies and advisor to the United Nations Security Council, looks at the quest for precision bombardment among America’s political leaders and military strategists – and why the increasing drone deployment by presidents Obama, Trump and now Biden has been the catalyst for a growing global proliferation of drones.

The book makes for sobering reading – the first drone strike came in 2001 and by 2023, more than 113 nation states have access to weaponised drones, and there are now terrorists who have access to “kamikaze drones”. As well as the present terrifying reality, Rogers looks at the history of precision bombing, and why Trump’s direct order for a drone strike to kill Iranian general Qasem Soleimani in 2020 was a “watershed moment” in international security. Looking ahead, the use of drones will, according to chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley, challenge the United States “in every domain of warfare”.

Precision is an academic study that raises some worrying questions in our troubled present.

‘Precision: A History of American Warfare’ by James Patton Rogers is published by Manchester University Press on 5 December, £20

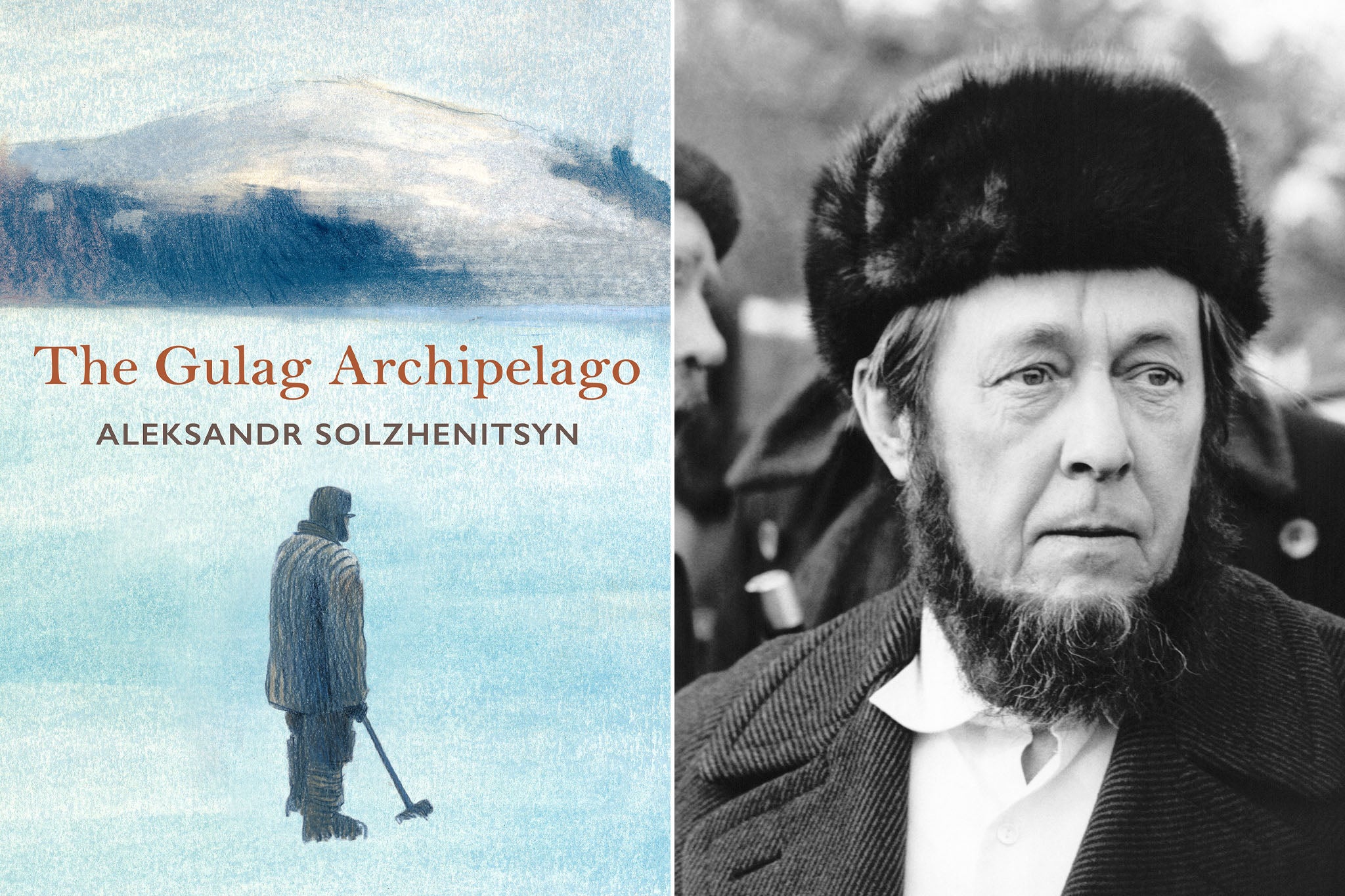

The Gulag Archipelago: 50th Anniversary Edition by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn ★★★★☆

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970 and who died in 2008, was one of the 20th century’s most important writers. The Gulag Archipelago, now re-released in a beautiful 50th anniversary edition, is a non-fictional account about the imprisonment, beating and very often murder of tens of millions of innocent Soviet citizens by their own government, mostly during Joseph Stalin’s rule, from 1929 to 1953.

Solzhenitsyn called The Gulag Archipelago his “main” work, seeing it as more important than his novels. In a new foreword to the book, his daughter Natalia Solzhenitsyn describes her late father’s work as “a book about the ascent of the human spirit, about its struggle with evil”. The book is deeply painful, but it continues to shine an important light on the worst of human behaviour.

‘The Gulag Archipelago: 50th Anniversary Edition’ by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn is published by Vintage Classics on 7 December, £25

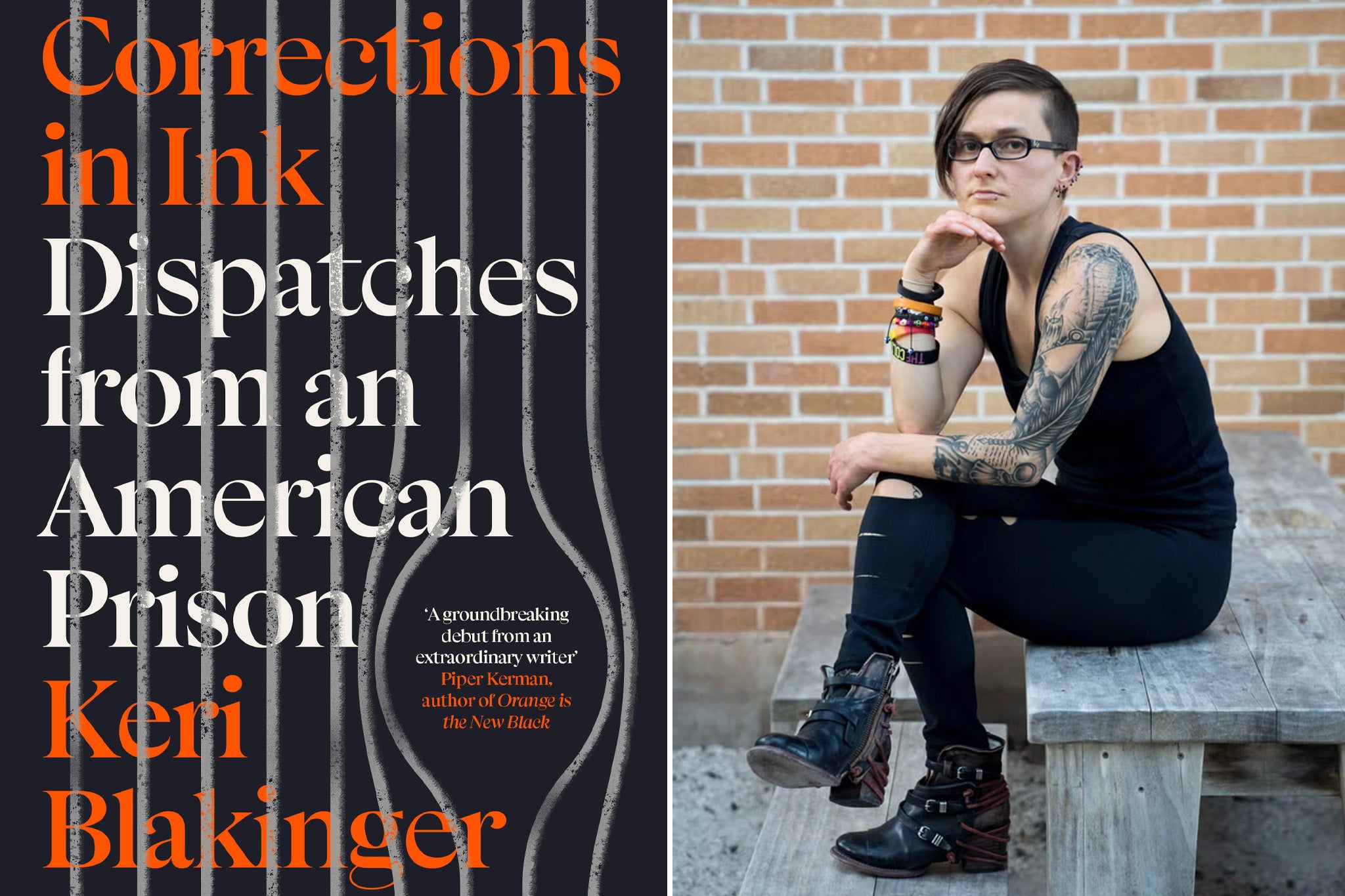

Corrections in Ink: Dispatches from an American Prison by Keri Blakinger ★★★★☆

“Being in jail is a constant lesson in humility, humiliation and powerlessness,” writes Ivy League graduate Keri Blakinger about her “two slow years in prison” after being arrested in 2010 with a Tupperware container of heroin.

Blakinger, born in 1984 in Pennsylvania to a lawyer father and teacher mother, recalls in graphic detail the road to incarceration, which included her eating disordered depression, bulimia, overdosing and working, while living like a “scabby, smelly junkie”, as an underage sex worker.

Corrections In Ink: Dispatches from an American Prison doesn’t set out to deliberately shock, but the American’s account of rapes, the men who pay $20 to “lick sweaty feet”, the married men who cry while having sex, the punters so old “they were incontinent and would soak the bed in urine, accidentally peeing on you and in you before asking for a blow job” and the men who asked her to pretend to be a six-year-old during sex, are gruesome and disturbing.

In the sections on her time in jail – including at Albion Correctional Facility in New York state – she explains what life is like when “behind bars, there are no rules”. Her experiences of prison – the warped guards, the volatility and threat of violence, the daily grind of eating cold, foul food in a mess hall “that reeked of sewage”, the mental health problems – are grim and truly eye-opening. Blakinger says prison is a place where the motto “gay for the stay, straight at the gate” is an accepted truth and where things are desperate enough for female inmates to “fashion strap-ons out of toothbrush holders and Ace bandages”.

Corrections in Ink is a bleak account of a life most of us will luckily never see, but it’s also a tale of redemption, not only in the moments of shared humanity Blakinger manages to find in prison, but also in the courageous way she pulled her life together after her release to become an inspiring investigative journalist. Her account of going on to expose wrongdoing behind bars, and helping prisoners with issues such as dental care, is really quite touching.

‘Corrections in Ink: Dispatches from an American Prison’ by Keri Blakinger is published by Icon Books on 7 December, £10.99

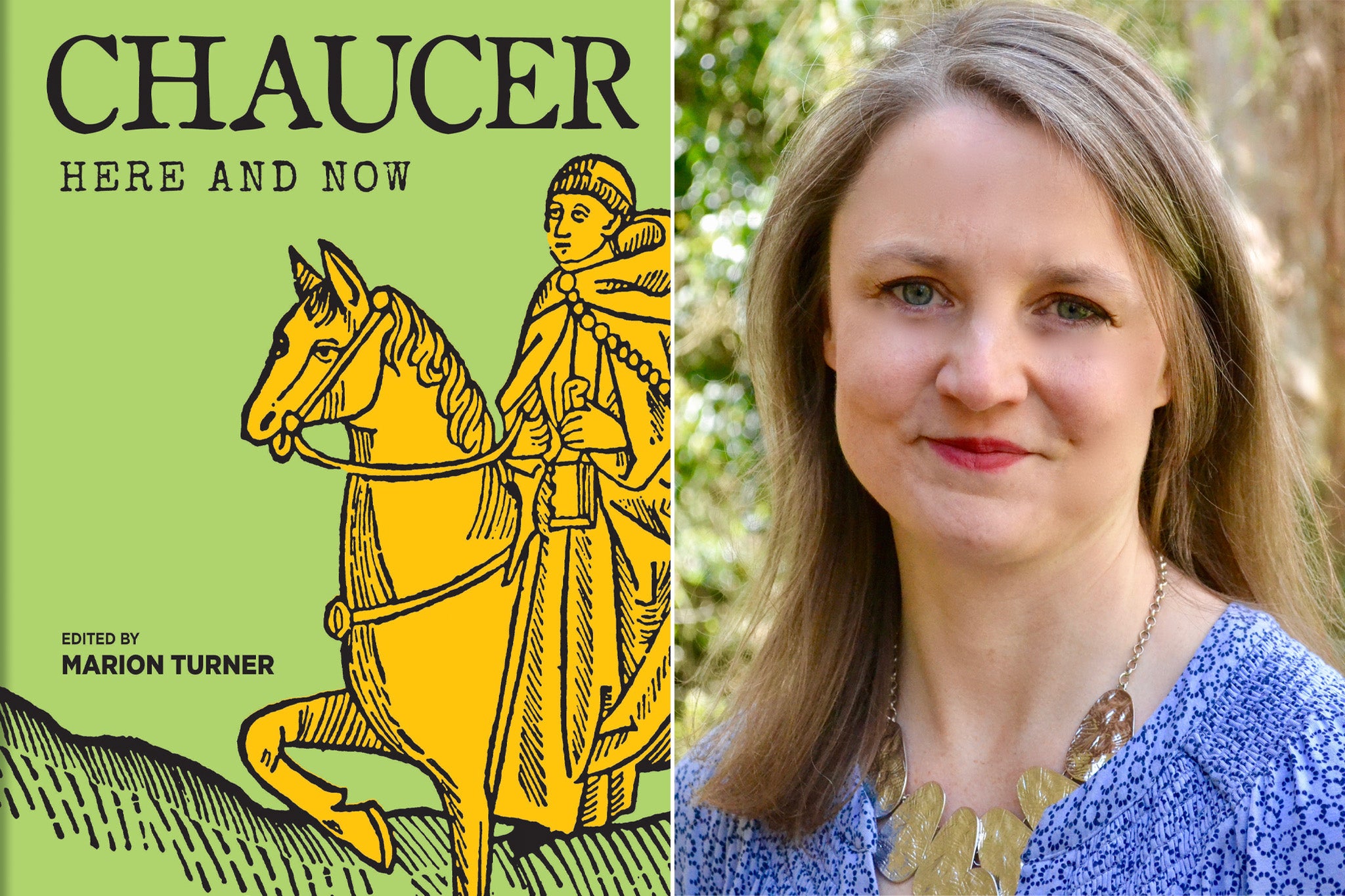

Chaucer Here and Now edited by Marion Turner ★★★☆☆

Chaucer’s earliest surviving poem, The Book of the Duchess, was composed around 1370. Nearly seven centuries later, Chaucer continues to fascinate and aficionados will be thrilled by Chaucer Here and Now, which contains gorgeous illustrations of early manuscripts and rare editions.

Six Chaucer experts – editor Marion Turner, Jeff Espie, Alexander Gillespie, Adam Rounce, David Matthews and Jonathan Hsy – contribute stimulating essays on the author of The Canterbury Tales. I particularly enjoyed Turner’s essay “Chaucer on Film and Television“ and her dissection of why Pier Paolo Pasolini’s notorious 1972 film of the Tales focused on “the horror of older female sexuality”, and why Londoner Chaucer would have been bemused by film adaptations that imagine the Englishness in his work as “fundamentally rural”.

This impressive book ends with a look at Chaucer in the digital age, and how, in the 21st century, “Chaucer is also finding his way into new media”.

‘Chaucer Here and Now’ edited by Marion Turner is published by Bodleian Library Publishing on 8 December, £30

The Small States Club: How Small Smart States Can Save the World by Armen Sarkissian ★★☆☆☆

Armen Sarkissian, former president of Armenia, picks out 10 states – Singapore, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Israel, Estonia, Switzerland, Ireland, Botswana, Jordan and Armenia – in his manifesto about the small nations who are best navigating the challenges of the 21st century.

The Small States Club is a curious book and made me wonder: who is this aimed at? There are idiosyncratic moments. Of Singapore, for example, the sixth wealthiest nation in the world, he praises the fact that “in the unlikely event that you spot a pothole, the authorities will fill and smooth it out within 48 hours of being notified”, something that would be a vote winner in the UK. His cosy account of Qatar believes that the critics of the host for the 2022 World Cup “remain blind” to the changes the football extravaganza brought to the country. Then again, human rights are not really the main concern of the book.

Sarkissian, who trained as a scientist, brings his own diplomatic experiences to the guide. The chapter on Israel is a lucid account of its origins and why “an absolute state of security” is seen as essential. The Armenian politician also states: “It was the Armenian genocide that inspired Hitler to proceed with his plan to deport and liquidate Europe’s Jews. ‘Who remembers the Armenians?’ Hitler had asked.” Sarkissian reminds readers that a million and a half Armenians were slaughtered by Turkey between 1914 and 1918. He registers his disappointment that Israel has “never formally recognised the Armenian genocide”.

Perhaps Sarkissian is right, perhaps small states are shining examples of how countries should be run. Some of his arguments just seem too fanciful, though. Can you really imagine, as the author does, that Ireland has the real potential to act as the mediator between the United States and China? Pass the Blarney Stone.

‘The Small States Club: How Small Smart States Can Save the World’ by Armen Sarkissian is published by Hurst on 14 December, £25

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments