Books of the Month: From Anne Enright’s The Wren, The Wren to Wifedom by Anna Funder

Martin Chilton reviews the biggest new books for August in our monthly column

When the police raided the Royal Vauxhall Tavern in 1987, during the height of scaremongering over Aids, the late television presenter and comedian Paul O’Grady noticed that the coppers were all wearing bright blue rubber gloves, as if mere contact with its mostly queer patrons represented a mortal threat of contamination. O’Grady grabbed a mic and joked to the crowd: “Well, well, looks like we’ve got help with the washing up.” This story, and countless other entertaining ones, appear in Ed Gillett’s Party Lines: Dance Music and the Making of Modern Britain (Picador).

Gillett’s well-researched, meaty account of dance music in the UK, chronicles the Black roots of the “movement”, the anti-dance moralism of the Margaret Thatcher years, the Manchester/Hacienda scene, all the way through to the corporate club landscape of the 21st century. The chapter “Plague Raving” deals with some of the truths and myths about what happened with “illegal raves” during lockdown. Party Lines is an engrossing piece of modern social history.

Finally, after Pilcrow (2008) and Cedilla (2011), Adam Mars-Jones’s wonderful creation John Cromer gets a third outing in Caret (Faber), which displays the author’s usual wit and insight in a story set in the 1970s. Fans of the series will have plenty to chew on, incidentally, as this third instalment comes in at just under 750 pages. That decade is also the setting for large chunks of John Niven’s moving memoir O Brother (Canongate), about the effect of sibling suicide.

The late writer Jonathan Raban described his father as “an alumnus of the old school of the stiff upper lip”. His mother was blunter, saying her husband had a “leather heart”. In Father & Son: A Memoir About Family, the Past and Mortality (Picador), written after the author suffered a stroke, Raban tells the story of his parents’ early marriage. The book is tender, wise and full of candour. In one surprising reflection, Raban, who died, aged 80, in January this year, mused on his “reckless” lifelong smoking habit, admitting he knew the dangers even when he began puffing as a teenager. “In the 1950s, long before the cigarette companies were made to print warnings on their products, we already talked of smokes as ‘cancer sticks’,” he recalls.

Finally, two of my favourite old Holborn drinking haunts crop up in Eloise Millar and Sam Jordison’s nugget-filled Literary London: A Book Lover’s Guide to the City (Michael O’Mara Books). The Cittie of Yorke in Chancery Lane, the setting for one scene in David Copperfield, features in their suggested “Dickensian Pub Crawl” of drinking venues in the capital. So too, does the charming old pub The Lamb, where, say the authors, poet TS Eliot used to head for a “quiet beer” when he sneaked out of his Faber offices.

A memoir by Catherine Taylor, fiction by Ann Patchett, Richard Russo, Jo Ann Beard and Anne Enright, and a book on Orwell’s wife by Anna Funder are reviewed in full below.

Tom Lake by Ann Patchett ★★★★★

Tom Lake is set in the pandemic, when Lara Kenison, now 57 and living on a cherry farm in rural Michigan, slowly reveals to her three grown-up daughters the story of her affair with Peter Duke, a Hollywood superstar. By the conclusion of the dazzling novel, the reader ends up knowing more than the daughters. Secrets are withheld in a story that offers small plot twists and revelations that pack the power of a defibrillator shock.

There are so many wonderful things about Tom Lake. The characters are varied and astutely drawn and the way Patchett – who has been writing great fiction for decades – handles Lara’s inner life is sublime. The humour is subtle and Patchett, the rough age of the protagonist, has telling things to say about the delicate dynamics between parents and their disconsonant children. Lara jokes that physically her daughters, Emily, Maisie and Nell are so different, “they might as well have been the three bears”. Lara also sums up the way that fathers and mothers are projected differently by using the device of the family watching “Duke” in an action movie. “Disappointment, the children learn early on, is embodied by the mother,” Lara reflects.

The novel, which has deft things to say about sexism, power dynamics, the effect of the climate crisis on the mentality of the young and the deep truths we all learn about life as we get older, is also, in its own gorgeous way, a love letter to acting, reading, farming, animal welfare and tennis. Dive into Tom Lake… it is a beautiful novel.

Tom Lake by Ann Patchett is published by Bloomsbury on 1 August, £18.99

The Stirrings: A Memoir in Northern Time by Catherine Taylor ★★★★☆

The “addictive, druggy aroma” of Vosene shampoo is just one of the many memories triggered by Catherine Taylor’s evocative and stirring memoir, set mainly in the 1970s and 1980s in Sheffield, the South Yorkshire city in which Taylor grew up after her family moved from New Zealand. Who from that era can forget the baking summer of 1976, when there were standpipes in the streets and a plague of ladybirds across Britain?

The book neatly balances a personal story – the problematic relationship with her father after her parents’ divorce and the fear of discovering she has an auto-immune condition – with an incisive social history of an era, told honestly through working-class eyes. I am sure the book must have been an emotionally draining one to write at times, especially in recollecting the trauma of dealing with an unplanned pregnancy.

The Stirrings is also a tale of what it’s like to grow up as a woman in a man’s world. Medical men don’t come out well in the book and neither do the police. Taylor grew up in a time in Yorkshire when the fear of the so-called Yorkshire Ripper was palpable. She offers a sobering reminder of how his victims were treated with contempt by incompetent investigators. Her own experiences of being a young woman at university in the early 1980s were also of “omnipresent harassment”.

Her account of the Greenham Common anti-nuclear protests of the 1980s is also enlightening, and Taylor offers the instructive side note that one of the Newbury magistrates who regularly handed out fines to the protestors was the mother of future prime minister David Cameron.

What Taylor captures so adroitly in The Stirrings is the way that the past is always full of such contrasting experiences. Recalling 1978, for example, she conveys the excitement of buying her first album (Blondie’s Parallel Lines) and her bemusement at trying to understand the horrors of the world, including the abduction of 13-year-old Genette Tate from a quiet country lane in Devon. “The image of Genette’s abandoned bicycle, one wheel still spinning, is indelible in memory,” writes Taylor in this excellent memoir.

The Stirrings: A Memoir in Northern Time by Catherine Taylor is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson on 3 August, £16.99

Somebody’s Fool by Richard Russo ★★★☆☆

Donald “Sully” Sullivan, an incorrigible old reprobate from the fictional upstate New York village of North Bath, is Richard Russo’s best known and most enduring character. After 1993’s Nobody’s Fool – adapted into a wonderful film starring Paul Newman as Sully – and the 2016 sequel Everybody’s Fool, comes the third instalment, Somebody’s Fool, set 10 years after Sully’s death. Sully is a hard act to follow and reading this book is an experience somewhat akin to enjoying a Tom Hanks movie and turning up to find the new one starring his son Colin. The Hanks quip isn’t fair, though, because the richest storyline in this new instalment involves Sully’s son, Peter, and his unexpected crisis with his estranged and angry son Thomas.

The other main plotline involves middle-aged retired Police Chief Douglas Raymer (played as a youngster by Philip Seymour Hoffman in the movie), who has to take over from his Black girlfriend Charice on an investigation into a bizarre suicide.

Dialogue heavy, Somebody’s Fool has sharp observations to make about modern America, reflected in the way that North Bath, now going to seed, is being subsumed and consumed by its gentrified neighbour Schuyler Springs. But overall, the novel is a mixed bag. The opening chapters sag with clichés such as “circling the drain”/“having a dog in the fight”/“it was time to pull the plug”/“rode hard and put up wet” (some of which are even repeated), and 74-year-old Russo’s story lacks the brilliantly jaunty and eccentric comedy of the first novel. Humour is subjective, of course, but lines such as “alcohol had been known to make Charice frisky, and they hadn’t frisked each other in nearly a month” felt flat to me.

I really enjoy Russo’s writing – his Pulitzer-winning Empire Falls is a magnificent account of small-town America – and there is still much to like in a 450-page novel that really hits its stride in the final quarter, thanks in no small part to a terrific scene involving a charged confrontation between Peter and North Bath’s violent, corrupt cop Del. Russo still shines at writing charming, engaging characters (ah, disturbed Tina, with her wonky eye) and for all its flaws, Somebody’s Fool still has uplifting things to say about the power of friendship and the allure of redemption.

Somebody’s Fool by Richard Russo is published by Allen & Unwin on 3 August, £17.99

Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder ★★★★★

Nearing his death, the shrunken, ailing George Orwell was reading an account of the life of Joseph Conrad, written by the writer’s wife. Orwell threw it across the room and hissed at his young companion Sonia, “Never do that to me,” forbidding any biography about him.

Orwell had good reason to fear an objective, honest account of his life, because the charge sheet against him is long and damning. Anna Funder, author of the excellent Stasiland, is a huge admirer of Orwell’s magnificent fiction and essays. This doesn’t sway her from painting a devastating portrait of an appalling human being. Funder’s book, a skilful blend of fiction, illuminating personal reflections and biography (including excerpts from letters by Eileen to her best friend Norah Symes Myles), lays bare Orwell’s self-absorption and selfishness in numerous small, telling details. His criminal, predatory behaviour I will return to.

This depressing fare should not obscure the main, laudable aim of Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life, a book in which Funder is determined to give a proper voice to Eileen O’Shaughnessy, Orwell’s first wife. She is a woman who has seemingly been somewhat airbrushed from history, Nineteen Eighty-Four-style, in seven previous Orwell biographies (all written by men).

Eileen, whose nickname, for reasons unclear, was Pig, had a rotten time being Mrs Orwell. She supported her husband financially and domestically, and was left to do all the s***y jobs – literally, as she was the one tasked with cleaning out the privy when the cesspool backed up in their ramshackle cottage. All the while, she encouraged her husband’s writing and stroked his ego.

Eileen, a vivacious and gregarious character, showed him ways of writing with more humour – evident in the difference people noticed in Animal Farm. She was a brilliant organiser and one-woman support team, yet she was given scant credit in Orwell’s own accounts of his life. Despite being a key part of the war in Spain, her name is not mentioned once in 1938’s Homage to Catalonia.

Orwell seems to have delighted in humiliating her, especially through his serial adultery. During a trip to Morocco, he told his wife he “deserves a treat” – and he didn’t mean an almond pastry. Instead, he wanted her approval to sleep with two of the “young” Berber girls who served him dinner. In a later chat with Harold Acton, Orwell salivated over “their slender flanks and small pointed breasts”. Funder speculates, incidentally, that Orwell’s hidden desire, “hidden perhaps from himself”, may have been for men. Who knows? Who cares?

Funder also details his record of attempted rapes, which were euphemistically known as his “pounces” on women. One such attempt, on a “friend” called Jacintha, left the teenager with torn clothes and injuries to her hip and shoulder. Depressingly, there were many, many instances. Perhaps it is Fender’s legal training – she has a combined Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Law honours degree and worked in human rights law before becoming a writer – that allows her to be so judicious, calm and analytical about his vile behaviour.

What the women who willingly slept with Orwell got out of their encounters is unclear. Celia Kirwan, a young magazine editorial assistant, recalled her disappointment at sex with the tuberculosis-ridden old Orwell, saying: “He makes love Burma-Sergeant fashion, afterwards saying, ‘Ah, that’s better,’ before he turned over.”

Orwell hit Eileen with one final wrecking ball, when he abandoned her to go on a trip while she was seriously ill from uterine tumours. Her tragic death, aged 39 at the hands of a careless and uncaring surgeon, is heartbreaking.

I guess, like me, most readers of Wifedom will be left pondering why Eileen, a talented poet, remained with Orwell through such terrible times. She clearly wanted him to fulfil his destiny, although any reflected glory seems such poor recompense, and her devotion came at the expense of her own talents and creative ambitions – as well as her mental and physical health. In this brilliant book, at least, she is lauded and exists fully. “I retrieved her from under her own self-erasure,” claims Funder. This seems to me to be what Orwell himself called “an objective truth” and, for once, an honourable “alteration of the past”.

Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder is published by Viking on 17 August, £20

Cheri by Jo Ann Beard ★★★★★

Jo Ann Beard, who was born in Moline, Illinois, in 1955, excels at describing pure sensory experiences and there is much to treasure in a new publication of her previously released essays and non-fiction narratives, The Collected Works of Jo Ann Beard. The pieces, from The Boys of My Youth and Festival Days, even include a joke about the “lizardy sound” of Mick Jagger. One of the works in the compilation is Cheri, which has also been republished as a single volume, and which is dedicated to Cheri Tremble (1950-1977), a woman who died from cancer.

Cheri was one of more than 300 people who were assisted in suicide by the late Armenian-American Dr Jacob Kervorkian, a polarising figure known as “Dr Death”. The book leaves you to make up your own mind about the ethics of euthanasia; after reading Beard’s haunting descriptions of what Cheri goes through, though, you can easily understand why Cheri made the choice she did.

Beard casts a cold and telling eye on terminal illness and she has a gift for original similes. For example, the first photograph of a lump in Cheri’s breast shows a cancer that looks tiny, “like a baby’s grasping fingers”. As a reader – as with Cheri’s daughters in real life – you are a helpless onlooker, left to gaze uneasily at nature’s whittling down of this woman. “It’s impossible to imagine not existing, she discovers, because in order to imagine, you must exist,” Beard writes.

The medical interventions are futile – and made worse by the horrible consequences of a botched reconstruction – about as effective for Cheri as “lion tamers holding out spindly chairs”. Although the content is undoubtedly bleak, Beard’s writing is majestic and ultimately offers some hope, because the book is essentially less about death and more about what it is to be alive. Cheri is only 76 small, large-print pages, proving that, in the hands of a maestro, less can be so much more.

Cheri by Jo Ann Beard is published by Serpent’s Tail on 17 August, £10

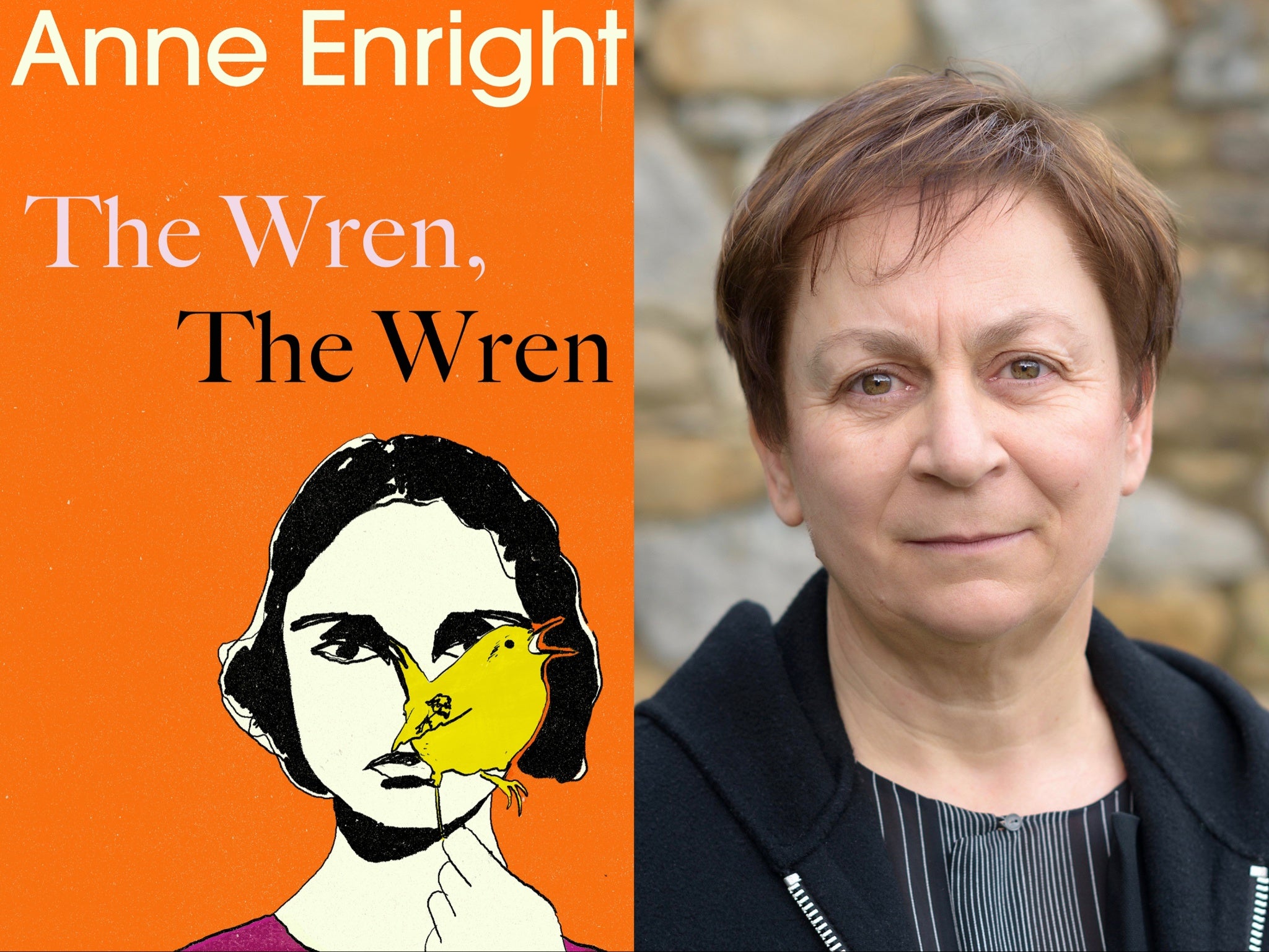

The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright ★★★☆☆

Anne Enright, former Laureate for Irish Fiction and Booker winner (The Gathering), explored parenthood in her excellent 2020 novel Actress, and she returns to the intricate emotions of family in The Wren, The Wren.

The multi-generational tale centres on mother Carmel and daughter Nell, each somewhat under the sway of Carmel’s father, Phil McDaragh, considered “the finest love poet of his generation”. His poem “The Wren, The Wren”, about the “blur of love” is dedicated to Carmel. He abandons his family just when his wife contracts terminal cancer.

Enright’s novel gradually unpicks a story of betrayal, loneliness, selfishness, and shows, in a compassionate, forceful way, the problems Nell faces navigating a cruel world. Her relationship with Felim, a disquieting and manipulative boyfriend, is sharply portrayed. “I think I am his leavings,” says Nell of a giant lad “raised on soda bread and rashers”. He is someone who always rouses in Nell “the idea that he will try to hurt me in some way”. In The Wren, The Wren, we see the modern world through Nell’s eyes and it’s not a likeable place.

Nell and Carmel are complex characters – Nell may well be the first person in fiction who praises Betty Davis’s song “Nasty Gal” – and Enright guides the reader skilfully to a conclusion where empathy matters and people can come back to their “true” selves.

The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright is published by Vintage on 31 August, £18.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments