Bob Dylan’s 1974 return was a watershed moment for music fans – I watched from the third row

After a motorcycle crash and eight years without touring, the legendary singer’s live comeback was the most galvanising music event in America since Woodstock. Jim Farber was there as a 16-year-old superfan, and recalls what it was like to be at the Oasis reunion tour of its day

On the morning of 2 December 1973, nearly 10 million letters started pouring through the US postal system for the same urgent purpose. Contained in each letter was a certified cheque, written with the sender’s sincere hope that it would secure them tickets for a concert that, apparently, every music fan in the world would crawl through shattered glass to see. The total dollar amount for ticket requests that started coming in that day – and which continued for the next three weeks – reportedly approached $92m, the equivalent of more than $664m today (or £488m).

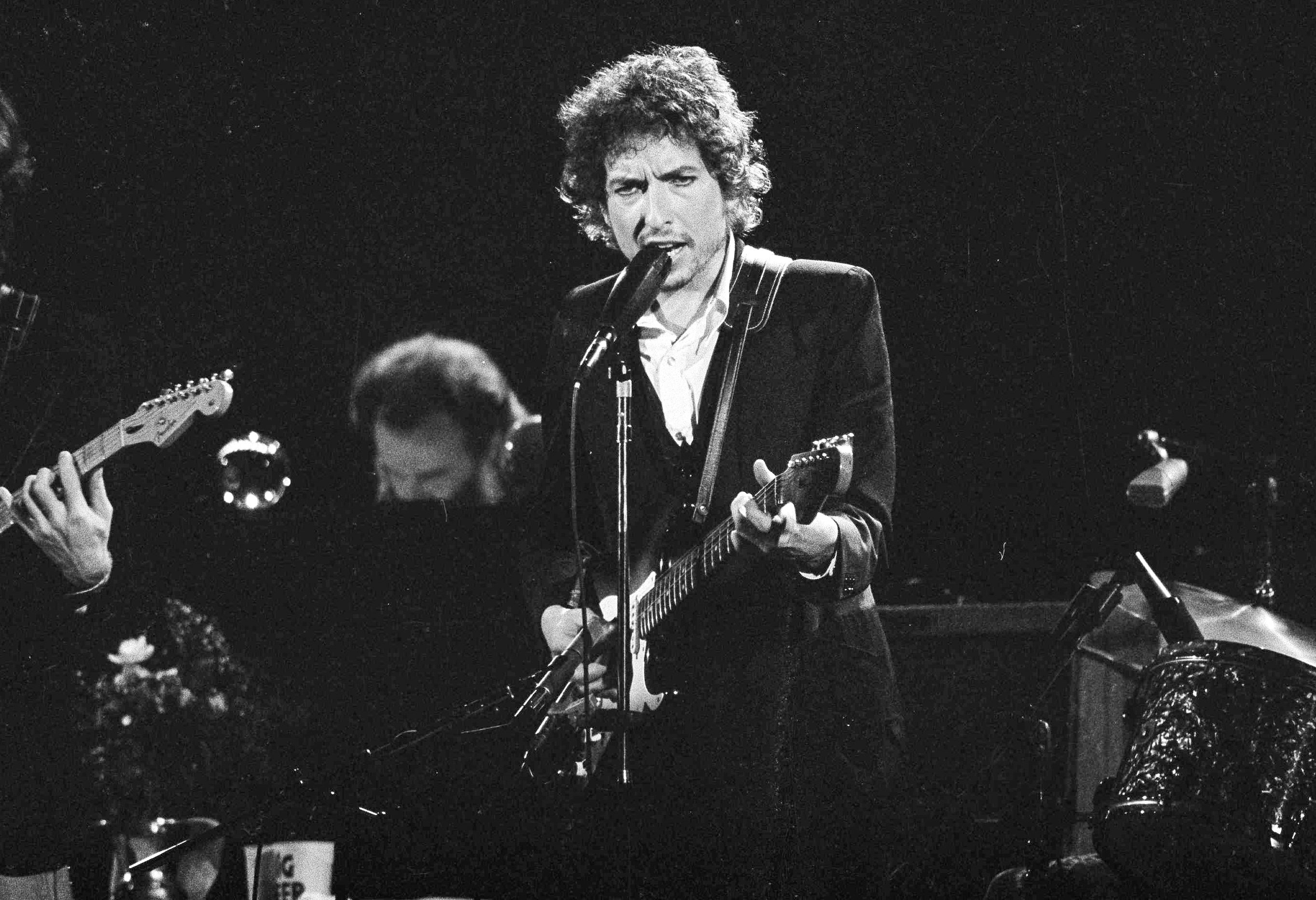

What could inspire such a crushing mix of commerce and passion that it required a lottery system simply for the right to buy concert tickets? No less earth-altering an event, it seems, than the return of Bob Dylan to the touring circuit after eight endless years. To make tickets for the shows even more prized, Dylan would be joined on the tour by The Band, the foundational Americana group that had backed him on his last national jaunt in 1966 when he “went electric”, to the later-to-be-lampooned boos and cries of “Judas” from benighted folk purists.

By 1973, the absence of Dylan from the touring circuit was so achingly long, it had outlasted the entire history of The Beatles in America. Small wonder that only a reunion of the Fab Four themselves could have out-hyped it. In terms of sheer demand, Dylan’s show could be considered the “Eras Tour” of its day, if not an antecedent to the Oasis reunion, only more coveted than either since it included far fewer dates, crowded into a brisk sprint through the US between January 3 and February 14 of 1974. No UK or European dates would be added. Fans whose mailed-in requests were fortunate enough to be selected earned the right to buy specific seats in the arena of the city to which they were sent.

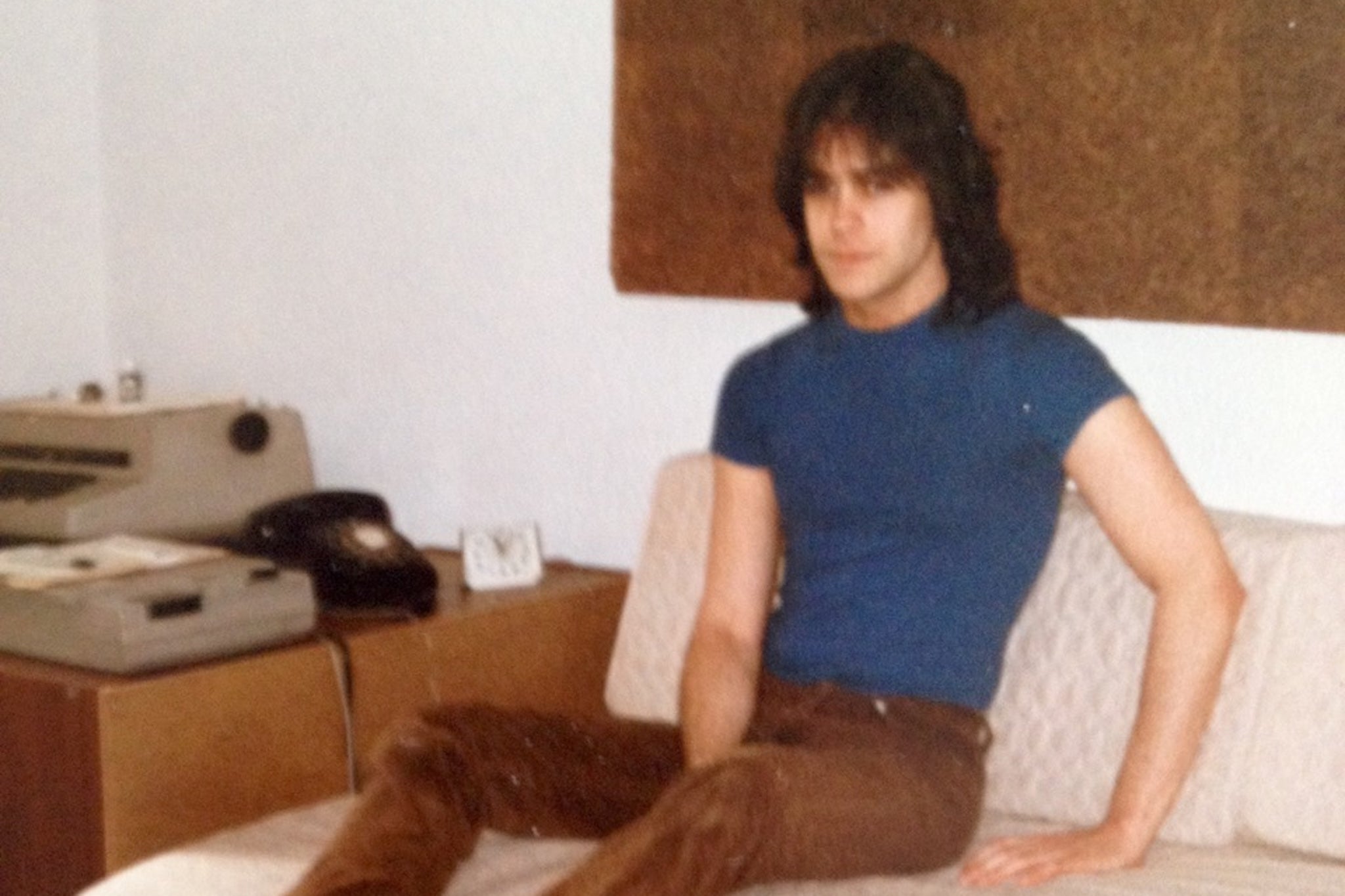

Given the intensity of the competition, it was a stroke of Lotto-level luck that yours truly – then a 16-year-old superfan – won the right to buy third row centre seats, a position so close to the stage, Dylan could have spat on me and my friends if he wanted to. At one point during the show – I believe it was during an especially feverish take on “It Ain’t Me Babe” – he actually did! The fact that the staging for the tour allowed no space for a photo pit meant that fans in the front rows were closer than ever to our gods.

As much excitement and press as the tour inspired – including the cover of Newsweek, as well as sufficient ink in Rolling Stone to later be compiled into a book – the tour has largely been forgotten by anyone who wasn’t around at the time. This is despite the fact that it was clearly the most galvanising music event since Woodstock in 1969 or The Concert for Bangladesh two years later.

Now that blind spot can finally be corrected with the release of a new box set chronicling the tour, titled Bob Dylan – The 1974 Live Recordings. A lumbering behemoth, the set contains every syllable Dylan performed during that historic jaunt. Though the box leaves out every song performed in separate sets by The Band during the tour, the result still balloons to 431 tracks, spread over 27 discs.

A staggering 417 of those tracks have never been previously released. The rest were contained on a double album culled from the tour, titled Before the Flood, released in June of ’74. Basking in the expanse of the box today brought back a tsunami of memories, as well as a fresh appreciation both for where Dylan was in his career just then and “what it all meant” for the culture at large.

At the time, Dylan wasn’t only a no-show on the concert circuit, a move initially caused by his motorcycle accident in the summer of ’66. He also hadn’t released an official album in three years, an unconscionably long stretch by that era’s frantic standards. While his last full album, “New Morning” from 1970, was one of his most melodically ravishing and sonically vivid, it was followed by the soundtrack to Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, which boasted just one significant track, “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door”, chased by a cobbled-together collection of outtakes under the name Dylan (1973), which the songwriter had no say over.

The latter album came about partly as an act of spite from his record company, Columbia, for whom Dylan had worked since the start of his recording career in ’62. The friction with his label started when he became dissatisfied with his contract, leaving him open to a lure by David Geffen to sign with his company, Asylum Records.

In September of ’73, Dylan took Geffen up on his offer, ditching Columbia (if only for a year, it turned out) to record an album backed by The Band that Asylum rush-released under the title Planet Waves on 17 January 1974. The move paid off: the album shot to No 1, marking the first time that Dylan had topped the US album chart. Only later did it become clear that the excitement over the album had more to do with the rarity of the roadshow than with the middling music itself. Planet Waves went gold on pre-sales alone, only moving another 100,000 copies after fans heard the actual music. Just one song from it resonates today: “Forever Young”.

As if to underscore the album’s flaws, the shifting setlists on the tour ignored most of its songs in favour of older, more beloved material. Not that the renditions of the oldies had the slightest hint of a retread. For the Before the Flood show they were remade entirely, creating a sound that was every bit as riveting as the hype had promised.

For me and my friends, the excitement began well before the music started. We arrived for our show at Madison Square Garden on 30 January early enough to ogle an entire petting zoo’s worth of stars in the crowd. By Dylan’s stipulation, no celebs were allowed backstage, thus forcing them to mingle with the hoi polloi. I vividly remember seeing the then-married couple, James Taylor and Carly Simon, seated several rows behind us, as were Paul Simon, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Nicholson and Yoko Ono (sans John), who each traded gossip and kudos in the aisles. By this point in the tour, the show’s structure and setlist was largely fixed, following several variations at earlier dates.

Thanks to the obsessiveness of the box set, we can now hear exactly how the tour progressed, beginning with the first show in Chicago, which kicked off with “Hero Blues”, an outtake from his 1963 album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. He rarely performed that song, before or since. In early shows, he also played “Nobody ’Cept You”, a song left off Planet Waves that bettered most of what made the final cut. The basic structure of the two-hour show featured a six-song opening burst by Dylan backed by The Band, followed by five songs from The Band alone, three more Dylan/Band collaborations, a five-song acoustic set from Bob, three or four more Band songs, culminating in a finale performed by both acts together. The choice of opening number for most shows, including mine, was also an unusual one – “Most Likely You Go Your Way, and I’ll Go Mine” – a lesser-known track from “Blonde on Blonde” that Dylan had never performed live before.

I vividly remember seeing the then married couple, James Taylor and Carly Simon, seated several rows behind us, as were Paul Simon, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Nicholson and Yoko Ono (sans John)

From its first notes, Dylan and The Band made clear they were creating a wholly new sound, marked by an aggression, at times even a mania, neither act had previously approached. Most of the songs were played at twice their normal speed, with four times the intensity. Dylan fired his words like bullets while The Band used their corresponding riffs like battering rams. In each phrase, Robbie Robertson’s guitar work matched the mockery in Dylan’s inflections, encouraging Levon Helm to pummel his drums with a zealous glee.

Garth Hudson’s array of keyboards, enhanced by a new Lowery string synthesiser, came on like a carnival barker’s bray. From there, the blitz never let up – not only in rockers like “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” where Robertson’s sharp-tongued leads answered and elaborated each note Dylan’s sneered, but in acoustic pieces like “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” where the tune’s tender beauty took on a tone of special longing. Such interpretations were the start of what would become a hallmark of every Dylan’s tour thereafter – his will to make each performance of a classic song sound new.

The shock of it didn’t sit well with all critics. Legendary writer Nat Hentoff found the show “disappointing”, while Lorraine Alterman in the New York Times wrote of the “hysterical edge” in the music, which she deemed “very theatrical, but musically very unpleasant”. Even Dylan himself later put it down in an interview with Cameron Crowe. “I was playing ‘Bob Dylan’ and The Band were playing ‘The Band’,” he said. “The highest compliments were things like, ‘Wow, lotta energy, man.’ It had become absurd.”

Of course, only a fool would trust an artist as wily and mercurial as Dylan to see their work the way a listener might. To this one, the show took every element that had awed me about Dylan – his insight, candour, passion, invention and range, not to mention his melodic beauty, singular character and, yes, energy – and gave them a steely new edge. Select elements of the show gained special meaning from that particular time and place. It became a staple of the tour that at each performance of “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)”, when Dylan shouted, “but even the President of the United States sometimes must have to stand naked,” the crowd would erupt in cheers.

We were responding to the ever-growing hatred of President Nixon, then mired in the Watergate scandal that would finally force him from office that August. Such generational resonance also electrified every performance of “Like a Rolling Stone”, which Dylan played with the lights of the arena in full blaze, as if to highlight the song’s stark power.

I can see that moment burning in my memory now, and though you can’t simply by listening to the boxset, you can certainly feel the punch of performances that met their moment so perfectly that, 50 years later, they still seem forever young.

‘Bob Dylan and The Band: The 1974 Live Recordings’ is out on 20 September via Columbia & Legacy Recordings

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments