Who will spare us from the actor’s novel?

Tom Hanks, Hugh Laurie, David Thewlis – everywhere you look there’s a screen titan turning to literary fiction. If only their books were as good as their acting, says Louis Chilton

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They say everyone has a novel in them. But that doesn’t make it a novel worth reading. For most, the path to literary success is steep, climbable only through some combination of talent, luck and salesmanship. If you’re famous, however, you get to take the escalator. Celebrity fiction is hardly a new trend, but it is one that’s inescapably in vogue. Where actors used to turn to directing to show off their artistic ambition, now the plaudits lie in self-penned pages of literary fiction.

Which brings me to Shooting Martha – the second novel by actor David Thewlis, to be published on Thursday. On screen, Thewlis is a force of nature; whether in early roles, such as the young, abrasive ne’er-do-well in Mike Leigh’s Naked, or in stealing every scene as the nefarious VM Varga in Fargo, Thewlis has proved himself one of the country’s finest and most distinctive screen actors. His novel, however, betrays little of this greatness. It is… fine. Just fine.

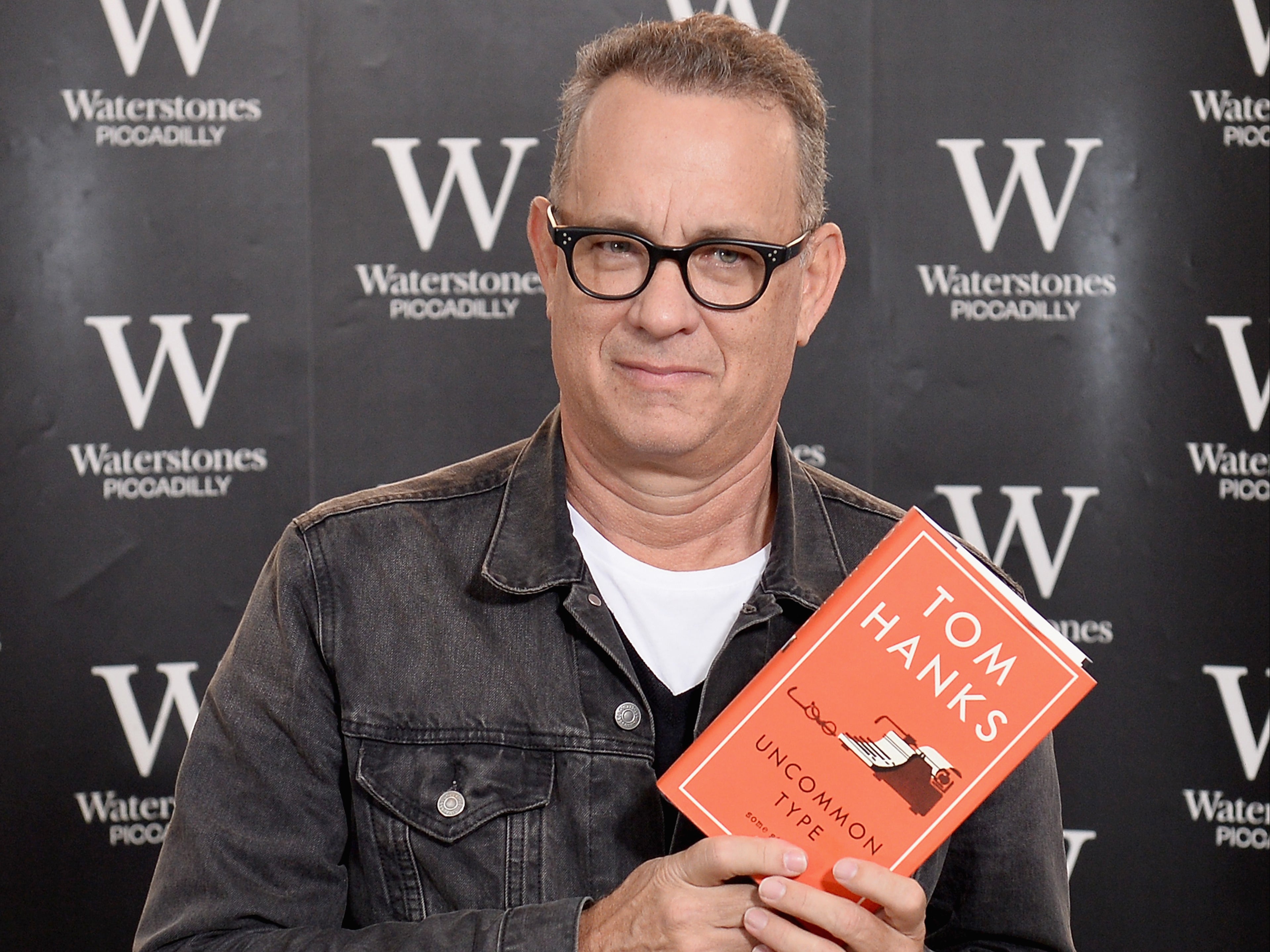

There is a long tradition of actors dabbling in prose fiction, one that includes everyone from Hilary Duff and Isla Fisher to Hugh Laurie and Tom Hanks. The film star-novelist figure dates back well into the 20th century: people such as Sylvester Stallone, Tony Curtis and Dirk Bogarde were doing it decades ago.

Earlier this year, Ethan Hawke released A Bright Ray of Darkness, a similarly unexceptional novel that fails to capture what makes its author such a powerful and noteworthy presence on screen. And why would it? Acting and writing share a number of what you might call “transferable skills” – understanding characters, navigating tones, exploring the “human condition” – but these are ultimately quite vague and ethereal. When it comes to the specific, practical skills needed to write, structure and refine a novel, acting is about as useful as carpentry or investment banking. This won’t matter to a publisher, mind you. If Tom Hanks walks into an office saying he wants to publish a book of short stories, it’d take someone with a pathological fear of money to even consider telling him no.

Filmmakers, too, have got in on the action. Quentin Tarantino’s novelisation of his 2019 film Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood proved one of the most talked-about literary events of this year when it was released last month. It went down agreeably enough with the director’s fanbase, but the prose is nothing special and inevitably lacks the inspired cinematic flair of his best screen works. Between the gratuitous tangents into film nerd trivia and eyebrow-raising mentions of feet, this was unmistakably Tarantino – but that’s probably the best you could say about it.

Other revered directors, including Tim Burton and Ethan Coen, have also turned their hand to fiction in the past, with underwhelming results. Coen’s 1998 book of short fiction, Gates of Eden, would probably be a perfectly decent set of stories were it anyone else’s debut book. But knowing that it’s from one of the two men who brought us The Big Lebowski, Inside Llewyn Davis and O Brother, Where Art Thou?, you can’t help but question whether his time would have been better spent elsewhere.

The traffic stalls in both directions, of course. The annals of cinema are littered with the ill-fated efforts of authors who thought they could play Hollywood – so much so that “you can tell this was written by a novelist” has become something of a cliché for reviewers. Even great novelists – John Steinbeck, Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy – have struggled to make their mark in the medium. Stephen King’s works have been adapted into some of the most enduring horror films ever made – but look down the list of projects he was personally involved in, and you’ll see a list of flawed, forgotten misfires.

Some have managed to make the transition successfully, however. Richard Price interspersed novel-writing with a career writing Hollywood scripts including The Color of Money and Sea of Love; in writing the script for The Third Man, Graham Greene helped create an immortal piece of noir cinema.

Michael Crichton crossed the threshold more successfully than just about anyone, writing and directing the original Westworld and adapting his own novel, Jurassic Park, for Steven Spielberg’s iconic dinosaur flick. Miranda July is probably one of the best recent examples of an artist enjoying creative success across both written fiction and cinema, but her films are still essentially acquired tastes, operating outside the Hollywood mainstream.

As all culture coagulates into one homogenous lump we call “content”, it’s easy to underestimate just how specialised individual art forms are. The rhythms, logistics and sensibilities of cinema are an ocean apart from prose fiction. The vast majority of great writers spend years honing their craft; for most, it is a full-time job. Between film shoots, press tours and whatever else they have going on, it’s hard to see how someone like Thewlis or Hawke would have the time to properly develop as a writer.

It would be ungenerous, however, to simply insist someone “stays in their lane”. There’s something inherently admirable about writing fiction; regardless of celebrity and public goodwill, it still takes courage to present a novel to the world, to expose it to dissection and potential ridicule. Just ask Morrissey, whose dismal 2015 novel List of the Lost was torn apart by everyone from broadsheet reviewers to the judges of the Bad Sex in Fiction award. Filmmaking is a collaborative process, but fiction – well, that’s pretty much all on you. There is no hiding in fiction writing: no sweeping score or luscious production design to save you. There are only your words, the images and ideas you yourself can conjure from nothing.

It’s far from ideal that publishers are investing time and money in books simply because of name recognition; you can’t help but wonder how many superior but unknown novelists are being rejected in their wake. But publishing has never been a meritocracy, no matter how much it likes to pretend otherwise. You can’t blame actors for wanting to make their voices heard. On some level, that’s all anyone wants.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments