Books of the month: From Stephen King’s Billy Summers to Susie Boyt’s Loved and Missed

Martin Chilton reviews six of August’s biggest releases for our monthly column

Do you grin or grimace at the thought that almost every celebrity now seems to believe they have a novel in them? This month’s crop of fiction includes actor David Thewlis’s second novel, Shooting Martha (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), which began life as a screenplay and evolved into a darkly comic tale about a film director and his dysfunctional marriage. Miles Jupp’s History (Headline) is the tale of a private school teacher called Clive Hapgood. Jupp is a likeably droll comedian and television panellist, and his witty novel has some telling things to say about British hypocrisy and the culture at independent schools, where students “generally leave with an innate capacity to be dishonest”. Finally, Fretted and Moaning (Rocket 88 Books) contains 52 short stories set in the world of music by Andy Summers, former guitarist of The Police.

Since we’re talking about books by the famous, I’d hazard that the thought of a historical novel by Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York, in which the protagonist is called Lady Margaret Montagu Douglas Scott, would be enough to send most people into a cold sweat (although obviously not her former hubby, Prince Andrew, given his “peculiar medical condition” of being unable to perspire). Her Heart for a Compass (Mills & Boon) is being promoted as “the debut of the year” and although I’m sure that the Duchess’s “co-writer” Marguerite Kaye, described as “an accomplished Mills & Boon historical author”, has done a tip-top job of fashioning a Victorian melodrama, I’d really rather read 400 Ikea wardrobe instruction manuals than 400 pages of Fergie’s “romantic” musings.

The problem of fame is a theme in John Boyne’s The Echo Chamber (Doubleday), which satirises the blighted world of social media in the tale of a celebrity couple and their three messed-up children. Among other fiction I enjoyed this month is Virginia Feito’s sharp debut novel Mrs March (4th Estate), which explores the question of identity. Her book has already been optioned by award-winning actor Elisabeth Moss. I would also recommend Andrew Greig’s highly entertaining historical novel Rose Nicolson (Riverrun), which is set in a turbulent 16th-century Scotland, and Elif Shafak’s The Island of Missing Trees (Viking), a haunting tale set in Cyprus.

There are three strong novels in translation out in August. Men In My Situation, by Norwegian author Per Petterson (Harville Secker, translated by Ingvild Burkey), is the tale of a man adrift and consumed by grief. Russian writer Sasha Filipenko’s Red Crosses (Europa Editions, translated by Brian James Baer and Ellen Vayner) is the tender story of a 90-year-old woman recalling the horrors she and her fellow Soviets have endured. Thirdly, To Walk Alone In The Crowd, by Spaniard Antonio Muñoz Molina (Tuskar Rock Press, translated by Guillermo Bleichmar), is the enchanting story of a flâneur, a man who saunters around observing society. Molina’s observations are worth catching.

“Talking to My Students About Porn” is one of six thought-provoking chapters in The Right to Sex by Amia Srinivasan (Bloomsbury). The Oxford University professor offers disturbing insights into the modern sexual landscape, in which porn has become “the normative standard of sex” for many young men. “What will the world look like once another generation or two has passed, when every person on earth will have come of age sexually in the pornworld?” Srinivasan muses.

George Makari’s Of Fear and Strangers: A History of Xenophobia (Yale University Press) looks at how “xenophobia has come back from the dead” since 2016. This important study by psychiatrist and historian Makari does not pull its punches. “Do gadgets once meant to connect you with a high-school flame ignite riots, get presidents elected, and foment mass murder? They already have. Welcome to the twenty-first century.” The answers to the timeless problem of xenophobia, Makari argues, “must be global as well as local”.

Anyone interested in the history of surgery will find much to amaze and startle in Paul Craddock’s Spare Parts: A Surprising History of Transplants (Fig Tree). I was engrossed by the chapter on teeth (1685-1803), which explained that 17th-century surgeons used to carve out the teeth of a baboon, leaving a bit of its gum still attached, draw the patient’s rotten molar and immediately plug the gap with the animal’s tooth. “With time, the baboon’s tooth and gum would knit itself into the patient’s mouth.” This “look-at-my-new-dentures moment” would require some skilful airbrushing in the age of Instagram.

Last but certainly not least, Lucy Jones and Kenneth Greenway’s The Nature Seed: How to Raise Adventurous and Nurturing Kids (Souvenir Press) is a valuable practical guide to helping children form a kinship with nature.

Novels by Susie Boyt and Stephen King, along with short stories by Bernard MacLaverty, non-fiction by Dave Goulson and memoirs by Jay Parini and Felix White are reviewed in full below.

Billy Summers by Stephen King ★★★☆☆

Billy Summers, the protagonist of Stephen King’s new novel, is an unusual assassin. Billy loves country singer Willie Nelson and pretends to be “slower” than he really is, keeping his love of Émile Zola and “binges on Ian McEwan” secret from the sort of mobsters for whom he is simply an extremely reliable hitman for hire.

Billy, normally so meticulous, accepts one last payday before he retires, untroubled by knowing little about his intended victim. “He has no problem with bad people paying to have other bad people killed. He sees himself as a garbageman with a gun,” writes King. Billy hides out in small-town America, biding his time before his “hit” turns up. He poses as a writer and, unexpectedly, begins to enjoy writing his own life story, including his memories of a tour of duty as a sniper in Fallujah, where he won two Purple Hearts. Becoming a writer makes Billy realise how “sordid and squalid” his actions have been.

After the inevitable double-cross, Billy goes into hiding. The first third of King’s thriller is taut and engrossing, but a far-fetched twist instantly punctures the tension of the novel. Billy rescues a gang-rape survivor called Alice Maxwell and she willingly becomes embroiled in his revenge mission. In Billy Summers, 73-year-old King has characters repeatedly use the crass word “rape-o” to describe a sexual assault perpetrator. King seems keen to establish Billy as an empathetic, non-sexist hero, but the novel is tonally all over the place. When Billy sees “a pretty little Latina maid” he immediately describes how his protagonist starts thinking of “an old Chuck Berry lyric, ‘she’s too cute to be a minute over seventeen’”.

The novel is a very mixed bag. You come across a sharp phrase (“He pays cash. Cash has amnesia”) as readily as clunky prose and overblown similes (as Billy tries to work out the motives of the people who set a warehouse fire, he decides to “ponder it in his heart, like Mary pondering the birth of baby Jesus”). Although some of the set-piece action scenes are gripping, the final section of the book, a plot line involving Billy’s pursuit of a paedophile called Roger Klerke, is unconvincing and fuzzy with conspiracy.

There are plusses. In the foul-mouthed ageing criminal Marge Macintosh, King has come up with perhaps his best female antagonist since Misery’s Annie Wilkes. Overall, however, Billy Summers is firing plenty of blanks.

Billy Summers by Stephen King is published by Hodder & Stoughton on 3 August, £11, Amazon.co.uk

It’s Always Summer Somewhere: A Matter of Life & Cricket by Felix White ★★★★☆

Musician Felix White, former guitarist of The Maccabees and co-presenter of the podcast Tailenders with Jimmy Anderson, describes cricket as “my roadmap for growing up”, and his utterly charming memoir, It’s Always Summer Somewhere: A Matter of Life & Cricket, captures the appeal of this magnificent game, one that is winning over new fans this summer with the 100-ball tournament.

The book skilfully blends an account of his musical coming-of-age with memories of the sporting heroes who defined his upbringing. His observations on the game are sharp and colourful – he calls Shane Warne’s famously unplayable delivery to Mike Gatting “a concoction of shock” – and the book also includes his own revealing encounters with retired cricketers. “Phoning Mike Atherton to talk about Allan Donald at Trent Bridge in 1998 is a bit like phoning Paul Weller to talk about The Jam or Bob Dylan to talk about folk music,” writes White.

White has an entertaining chat with Ashley Giles, one of the true stars of that memorable 2005 Ashes triumph, who tells him he “screwed up” his A Levels and ended up working in a petrol station for eight months. Giles also tells him a fun story about the aftermath of becoming a national hero, when his management team started a fan club and ordered mugs with the words “King of Spin” on them. The printers, clearly not cricket fans, sent them back with “King of Spain” on the side.

The music tales in the book are interesting too, especially White’s accounts of getting his own career off the ground. There is a humorous account of his first gig at Kingston Peel, when a youngster from the support act came onstage to retrieve his drum kit. “’I’m so sorry’, he said, as we wrestled parts of the hardware back that he was beginning to pack up amid feedback and clanging, ‘but my mum’s outside and she says we have to go now’.”

What elevates the book above a formulaic “love letter” to my favourite sport is the way White offers such a personal, touching window into his own life. He talks about his uncle Paul, a man who was still harking back to the disappointment of being bowled first ball at boarding school some three decades later, and about his grandmother Abla, a proud Palestinian, who walked around with a black eye for two weeks after a cricket ball smashed her in the face during a game in the garden in which she was the wicket-keeper.

The most important figure, though, is his mother Lana, who died from multiple sclerosis when White was only 17. The book candidly explores how “unprocessed grief” affected his life as he became famous. The book includes a moving email from White’s father Andrew, written 13 years after Lana’s death, in which he tells his son how much he meant to his mother.

White’s perceptive, warm-hearted book will make you understand why he is an obsessive about the game and how it has shaped his life. He includes a telling comment from girlfriend Florence Welch, who says, “when you had the cricket on, there was just this glow about you. It’s the happiest I ever saw you, which was quite hard to compete with.”

It’s Always Summer Somewhere will knock you for six.

It’s Always Summer Somewhere: A Matter of Life & Cricket by Felix White is published by Cassell on 5 August, £20

Silent Earth: Averting the Insect Apocalypse by Dave Goulson ★★★★☆

Kurt Vonnegut offered a sombre verdict on the human race and the damage we are doing to the glorious planet we inhabit. “We could have saved the good Earth but we were too damned cheap and lazy,” the late novelist lamented.

Insect life has declined in abundance by 75 per cent in the past half century. The consequences are devastating, because the human food supply is directly dependent on the presence of sufficient land-based and freshwater insects. “As insects become more scarce, our world will slowly grind to a halt, for it cannot function without them,” writes Dave Goulson, who did a PHD on butterfly ecology and is now professor of biology at the University of Sussex, in Silent Earth: Averting the Insect Apocalypse.

Using groundbreaking research (the book is full of grimly fascinating charts and diagrams), Goulson details the host of factors behind insect decline, including deforestation and habitat loss, invasive species, foreign diseases, and mixtures of pesticides, fertilisers, climate change and light pollution. What’s happening to bees and butterflies is heartbreaking.

Silent Earth is an important, riveting book, which should be compulsory reading for politicians and businesspeople around the world. Goulson’s bleak autopsy on how our soils, rivers, lakes, hedgerows, gardens and parks have been contaminated with mixtures of man-made toxins should enrage any right-thinking person. Things are worsening rapidly. Goulson notes that “one of the first actions of the government post-Brexit in January 2021 was to grant a derogation for the use of banned neonicotinoids on sugar beet, despite fierce protests from environmental groups”.

We are up against profiteers, of course, including the businesspeople in Britain who are lining their pockets with global sales of Paraquat – a chemical herbicide known to cause all sorts of horrendous neurological diseases. Despite knowing exactly why it is dangerous enough to be banned in Europe and the UK, a firm in Huddersfield is exporting more than 122,000 tonnes a year to places such as Brazil, Guatemala and India.

Hypocrisy is not the preserve of Britain’s leaders, though. Goulson suggests that changing weather patterns mean that Russian ports are becoming ice free and vast tracts of northern lands that are currently too cold for crop production will become viable for growing cereals. “We should not expect help in tackling climate change from Vladimir Putin any time soon,” he notes.

Along with depressing nuggets – how pesticides are causing eggshell thinning (they break before birds can hatch) and damaging the gut flora of bees – Goulson also offers up fascinating tidbits about insects, including the edible ones. He explains that boiled wasps with rice was a favourite dish of the late Emperor Hirohito, but these lighter moments are small hors d’oeuvres in a banquet of misery.

The author, in eloquent prose, explains why large parts of the world will become more or less uninhabitable for humans and wildlife – and that horror is coming ever closer, as the recent floods in Germany, Belgium, Holland and China demonstrate. Goulson has three children and admits: “I am deeply worried that they are set to inherit an impoverished and degraded Earth.” I thought about all our children, my own three included, as I braved the chapter “A View from the Future”, in which he imagines what the world will be like in the 2060s – when the rampant malaria hitting the UK will be the least of anyone’s worries. This is a genuinely terrifying vision.

In the section “What Can We Do?” Goulson offers a host of constructive solutions to this crisis. Silent Earth is a clanking alarm call. We ignore these warnings at our peril. Otherwise, the human race is committing ecocide on a biblical scale.

Silent Earth: Averting the Insect Apocalypse by Dave Goulson is published by Jonathan Cape on 5 August, £20

Blank Pages and Other Stories by Bernard MacLaverty ★★★★☆

The 12 short stories from Belfast-born Bernard MacLaverty are of real depth and quality. There is a skilled accuracy to his portraits of human flaws and sorrows – and his tales are all the more poignant for being understated. In “Searching”, for example, MacLaverty makes a cricket ball the focal point of a story about sectarianism and military behaviour in a fractious Northern Ireland in 1971.

There is an impressive emotional range to Blank Pages and Other Stories and MacLaverty adroitly uses historical settings that reverberate with contemporary meaning. In “Blackthorns”, set in County Derry in 1942, science is the only hope for a man perilously ill with blood poisoning. The masterful “End of Days” imagines the final moments in the life of controversial artist Egon Schiele, who is watching his pregnant wife die of Spanish flu in the pandemic of 1918. A warning for that one: it contains a distressing description of being witness to a horrible death, in a tale with a darkly surprising twist.

In “Blank Pages”, MacLaverty summons up the life of a lonely widowed author, bringing touching warmth to the picture of his life in a wry description of the way the protagonist reads a local newspaper denuded of sub-editors. Vera, the main character in the moving “Wandering”, is a middle-aged teacher looking after a mother with dementia. She even gets to write for The Independent (in the story), noting that, “Oh, they’ll pay a bit. Not much, mind you.”

Although many of the tales are sorrowful, MacLaverty also brings some sunlight to the collection, especially in “Sounds and Sweet Airs”, an uplifting story about a harp player’s chance encounter with an elderly couple on a boat trip to Ireland. If short stories are your thing, you will cherish this collection.

Blank Pages and Other Stories by Bernard MacLaverty is published by Jonathan Cape on 5 August, £14.99

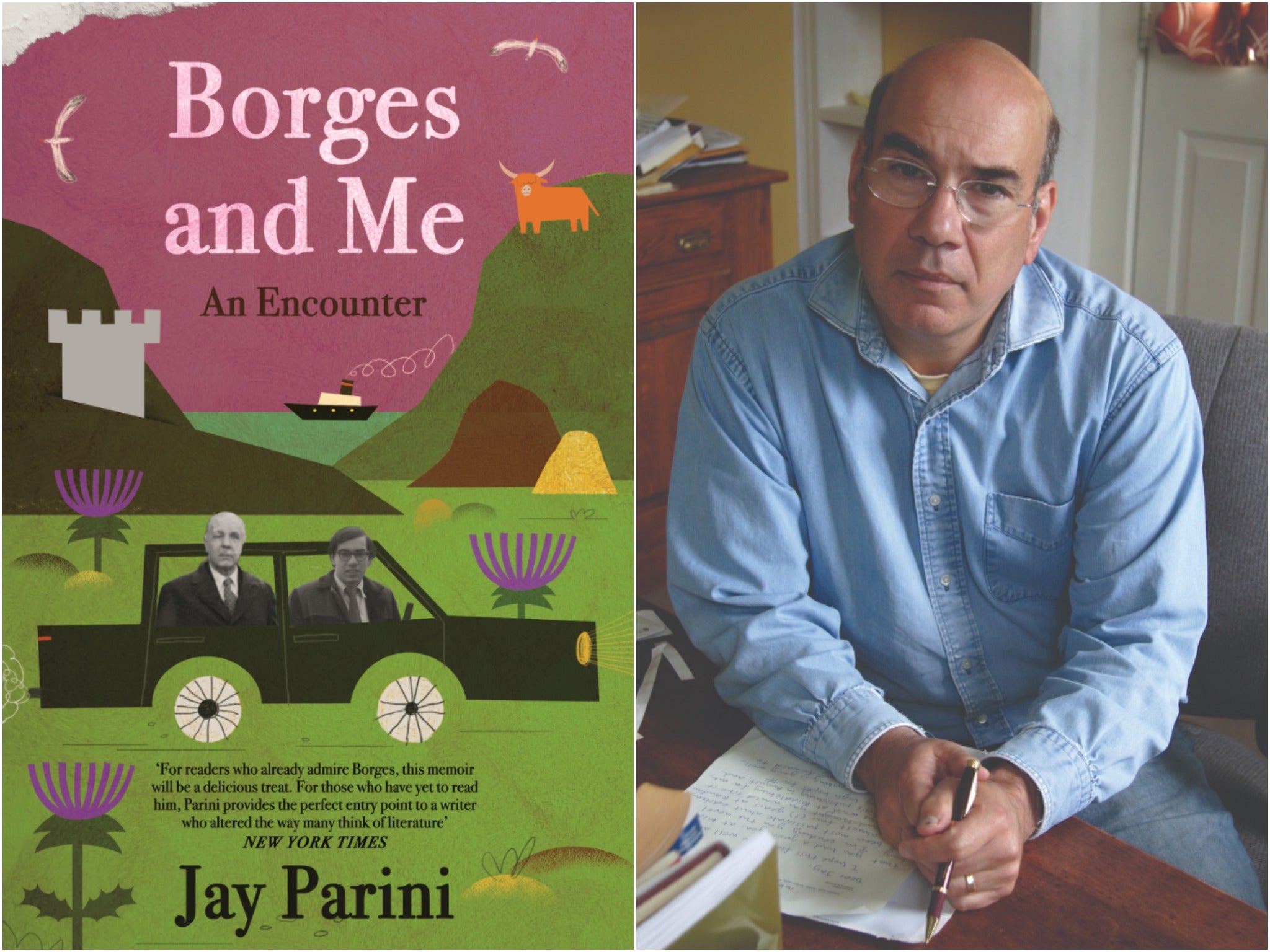

Borges and Me: An Encounter by Jay Parini ★★★★☆

As memorable road trips go, spending a week touring the Scottish Highlands with famed Argentine fabulist Jorge Luis Borges, then blind, frail and in his seventies, would undoubtedly leave a lasting impression. Out of that late 1960s trip, taken when he was a graduate student at St Andrew’s University and studying abroad to avoid being drafted for the Vietnam War, Jay Parini has created a novelistic memoir called Borges and Me.

Parini’s previous biographies of Gore Vidal and John Steinbeck established that he is a shrewd observer of literary grandees, and in this book he offers a wonderful portrait of an eccentric, brilliant writer. Borges was, he says, “a one-man literary spectacle”. The tales of driving round remote areas in a weather-beaten Morris Minor (which Borges names Rocinante, in honour of the lazy old horse in Don Quixote) are captivating. Borges demands that the young American student finds unusual ways to describe the scenery, asking him to “find metaphors, images. I want to see what you see. Description is revelation! Words that create pictures. Like the cinema, perhaps. Moving pictures.”

There are some splendid set-pieces – including the account of a near-disaster on Loch Ness, and of the painful night spent at a grubby B&B, in which the pair share a urine-smelling, sweat-soaked bed, It’s hard not to shudder at Parini’s memory of staying awake listening to Borges farting loudly. He captures the oddity of the famous author in an account of a visit to the Carnegie Library, during which Borges grabbed a book off the shelf, in front of the librarian, and “began to greedily lick the spine, his tongue like that of a cat”.

Borges, who calls the Scots “a disappointed people”, had a quick-fire, random mind, constantly offering up trivia from his vast store of knowledge, including that the worst smell in the world is ostrich p*ss, and that human ears are a true delicacy to cannibals. He was also capable of creating memorable verbal images. “I look inward now, though the mind has mountains, dangerous cliffs,” Borges tells his young holiday guide.

During the trip, Parini is worrying about his friends fighting in Vietnam while also pining for a fellow student called Bella. During a brief interlude, in which he leaves Borges to visit poet George Mackay Brown, the 22-year-old loses his virginity to a publican’s daughter called Ailith. She whispers in his ear that he was a “right good f**k” as they part. It’s hard to say how much is invented, re-imagined or exaggerated in the book (Parini kept limited notes at the time), but that doesn’t detract from the enjoyment to be mined from this wonderful literary adventure.

Borges and Me is a funny, affecting book, and some of the best moments are when the interaction with the old Argentine prompts Parini, now 73, to think about his own father. “Like many of his generation, children of the Great Depression, my father suffered from a pervasive cautiousness. The sidewalks of his mind were strewn with banana peels,” says the author, in one of the numerous sparkling phrases in an exquisite book.

Borges and Me: An Encounter by Jay Parini is published by Canongate on 5 August 2021

Loved and Missed by Susie Boyt ★★★★☆

The central characters in Susie Boyt’s Loved and Missed are all in pain, struggling with life, aware of what it means when someone admits, “I feel as though my pilot light has gone out”. This beautiful tale of love, courage and compassion is centred around teacher Ruth and her granddaughter Lily, the child she is raising after having removed her from Lily’s drug-ravaged mother Eleanor.

Boyt captures the pain of estrangement in penetrating, haunting language. “I was at sea with her and without her, out of my depth, famished, debased and drowning,” admits Ruth as she contemplates her daughter’s fate.

Ruth acknowledges that her own life is “smashed up”. Through her sensitive lens we are offered a heartbreaking portrait of parenthood, and her pain at seeing Eleanor’s physical plight (“she was like a haunted house at the fair”), as Ruth’s daughter turns from a happy-go-lucky child into a damaged, “reduced” young woman, with a “wintry” hardness in her face and in her character. Loved and Missed is a painfully acute portrait of addiction, all the more haunting for being devoid of vicarious, graphic descriptions. It is a subtle study of ethical decline as much as of physical reduction.

Men are a pretty unimpressive bunch in the novel, although the feckless, absent fathers remain minor characters in a story that is essentially about powerful, robust women: Ruth, her blunt-speaking friend Jean and the resilient, remarkable Lily, whom we see grow up during the course of the novel. Lily is never thrown off “the scent of what’s important in life” despite all her personal sorrows.

Loved and Missed is a complex, deeply moving novel about frailty and suffering. Despite all the sadness, hope remains. As Lily remarks, “sometimes in life you have to let your heart and bones off the hook of yourself”.

Loved and Missed by Susie Boyt is published by Virago on 26 August, £16.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments