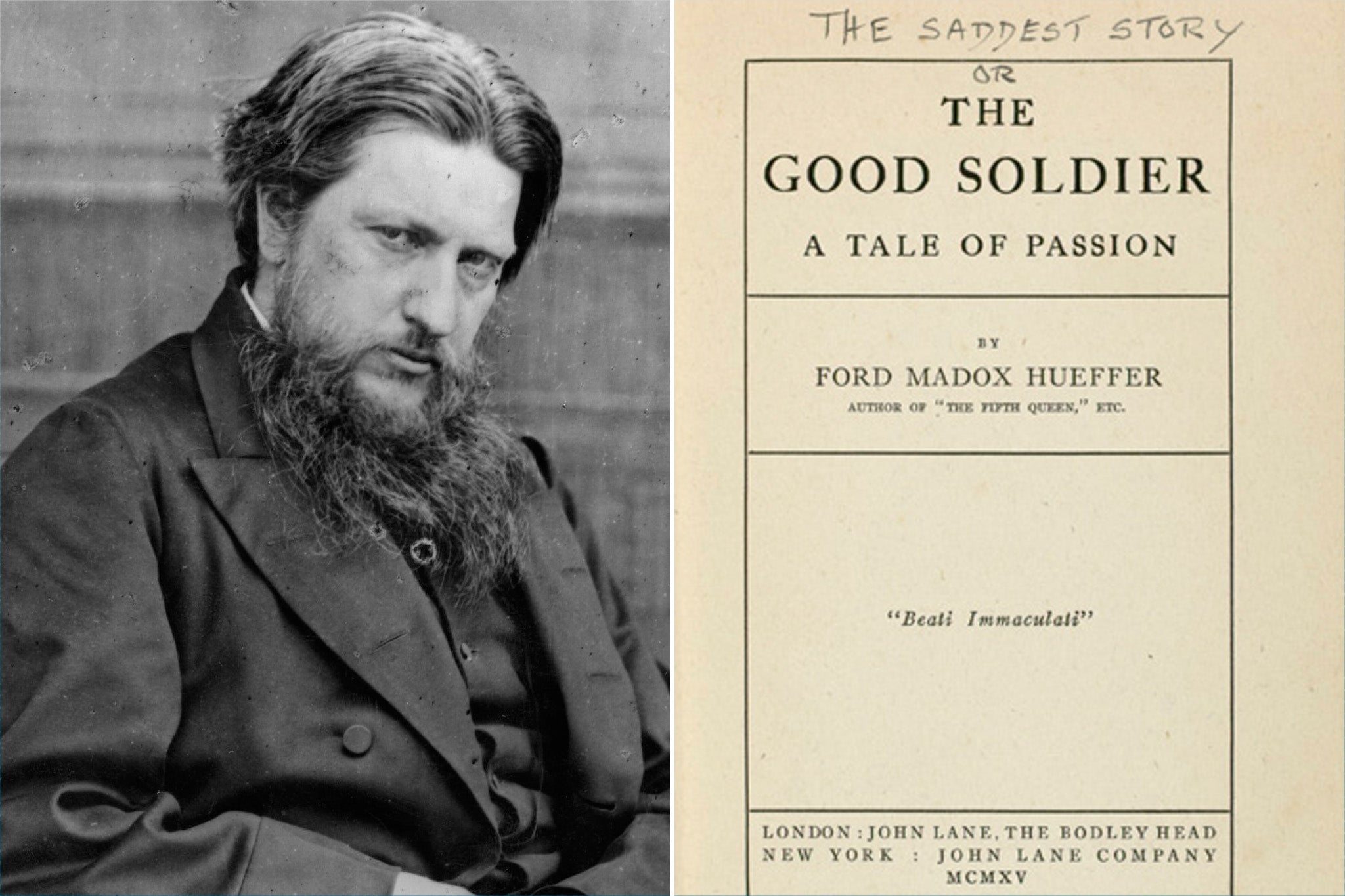

Book of a lifetime: The Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford

From The Independent archive: Kate Summerscale finds that her bewilderment and fascination with the delicate and devastating ‘The Good Soldier’ echoes the narrator’s own feelings

I came across Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier: A Tale of Passion when I was in my teens, in a box of my late grandmother’s books. It was a paperback edition of Ford’s novel of 1915, published in the US in the 1950s; perhaps my grandmother, who was American, had bought it on a trip home after the war. Its stiff cover bears an ink drawing of a man and woman in a smudgy embrace, each of their faces obscured by the other; another man is turned towards them, standing stock still, his face a pale whorl.

When I read the book, I was gripped but baffled by it. Afterwards, I remembered only its mysterious, confused atmosphere, passionate, messed-up, blurred. When I read the novel again several years later, I understood a little better what had compelled me, not least that both my bewilderment and my fascination echoed the narrator’s own.

Our narrator, an American called John Dowell, relates how he and his wife, Florence, befriended an English couple during their annual visits to a German spa. As Dowell much later learnt, Florence embarked on a long affair with the Englishman, a former soldier called Edward Ashburnham. The consequences were terrible.

Yet Dowell’s narrative shudders with his own feelings. It is driven by his will to understand, and twisted by his dread of doing so

“This is the saddest story I have ever heard,” Dowell begins, as if the story and the sadness belong to someone else. “You ask how it feels to be a deceived husband,” he says. “Just heavens, I do not know. It feels like nothing.” Yet Dowell’s narrative shudders with his own feelings. It is driven by his will to understand, and twisted by his dread of doing so. He rambles and digresses, circles and dodges, only for the skittering surfaces to be suddenly stabbed through with an over-vivid image, an odd joke, a stark assertion. “I know nothing – nothing in the world – of the hearts of men,” Dowell says, his desperation somehow still staved off by rhetoric. “I only know that I am alone – horribly alone.”

Ford originally named his novel The Saddest Story but his publisher, arguing that such gloom would not play well with the public in 1915, asked for another title. Archly, sarcastically even, Ford proposed The Good Soldier. He later regretted the change of title, and he was right to do so. The heavy-handed irony of the new name is a travesty of the delicate and devastating ironies of the story within.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments