Eyes front: Selfies from the Somme

In the run-up to July's centenary of one of the bloodiest battles in human history, The Independent is publishing a different Tommy's picture every day throughout June

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There were no “selfies” taken at the battle of the Somme. If instant communication had existed, the battle of the Somme – the bloodiest in British history and one of the bloodiest battles in all history – could not have dragged on for 141 brutal days starting a century ago next month.

Something comparable to “selfies” – the 1916 equivalent of selfies –did exist. They were lost for almost 100 years before they resurfaced a few years ago in skips and attics in northern France and then in the pages of The Independent.

The pictures were the work of an amateur French photographer called Alfred Dupire, who lived just behind the British front line in the Somme in 1916. For a few francs each, he took hundreds – probably thousands – of pictures of British soldiers which they sent home as postcards to their loved ones.

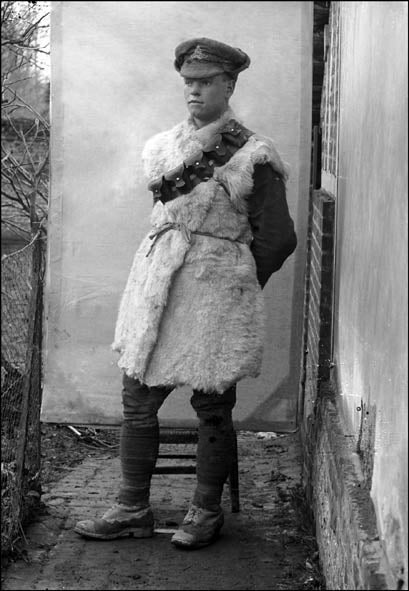

We make no apology for calling these images “Somme Selfies”. Like the selfies of the 21st century, the portraits were intended for a very limited audience of family or friends. They are a mixture of the unusual and the banal; the in-focus and the out-of-focus; the neat and the scruffy; the solemn and the jokey; the young and not so young; the carefree and the scared.

There are individuals, pairs, small groups and big groups.

There is even a black artilleryman (one of the few images ever found of a black British Tommy from World War One).

French civilians sometimes appear, especially two little girls who sit with solemn faces on the soldiers’ knees. A dog occasionally turns up.

Many of the portraits feature the same battered white door or the same wooden chair and the same back garden in the village of Warloy-Baillon, eight miles behind the British front line.

Over the last seven years, The Independent has published several batches of these images – over 700 in all. They have been scanned digitally from old glass photographic plates located in barns and attics, jumble sales and rubbish skips by three local collectors. Anyone who tours the many Somme cemeteries is confronted with the names of thousands of soldiers without faces. Here, we have the opposite: hundreds of soldiers’ faces without names.

Only two or three of the soldiers in the images have ever been identified. Many, quite possibly, died soon after their pictures were taken. When first published, the photographs generated extraordinary interest from all over the world. As the centenary of the Somme approaches, we publish a selection again here today as a tribute to the largely amateur British army which fought in the most ghastly single battle of a ghastly war.

Over the next month, up to the centenary of the first day of the battle on 1 July, we intend to publish a “Somme Selfie of the Day” on the Independent website.

Until a dozen years ago, at least one large trunk full of such glass plates survived on the Somme. There were probably many thousand pictures in the original collection, which was scattered in 2004. Most appear to have been thrown onto rubbish heaps and lost. Other such collections are known to have existed. Similar photographs taken in another village behind the Somme lines have recently been published in “The Lost Tommies” by Ross Coulthart.

Our images survived thanks to the efforts of three local men: Bernard Gardin, aged 67, a photography enthusiast; Dominique Zanardi, 51, proprietor of the “Tommy” café at Pozières, a village in the heart of the Somme battlefields; and Joel Scribe, 50, a local builder and collector of World War One memorabilia

By talking to people in Warloy-Baillon, and to descendants of the photographer before they died, Mr Scribe established how the pictures came to be taken. “Alfred Dupire was not a professional photographer. He was a businessman and quite well off but his hobby was photography,” Mr Scribe said. “When a new British unit arrived in the village, the word would go round that they could have their picture taken for a few francs and he would sell them postcards to send home.”

“Before he died a few years ago, Dupire’s grandson told me that the soldiers would queue in the street waiting for their turn.”

Each batch of images is dominated by soldiers from a single regiment. There are also many medics because Warloy-Baillon was the location of a hospital for soldiers who had suffered stomach and chest wounds.

Many of the tommies wear the distinctive cap-badge of the DLI – the Durham Light Infantry. There are also fine portraits of Scots soldiers in bonnets with Highland Light Infantry badges. Both the DLI and the HLI played a big part on the bloody first day of the Somme.

There are also Gloucesters, Sherwood Foresters, Royal Engineers, many artillerymen and members of the Machine Gun Corps. The Scots soldier shown here in his kilt sharing a cigarette and a joke with a friend from the |Machine Gun Corps is one of the two or three of our tommies to be identified. He was James “Jimmy” Hepburn of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, aged 18 at the time of the battle. He survived the war to marry twice, have nine children, at least 20 grandchildren and a still expanding army of great-grandchildren. He died in 1962, aged 64.

Since 2010, when two photographs of him first appeared in The Independent, he has become modestly celebrated in his native land. His grand-daughter, Alvine Swanson, an English teacher in Edinburgh said: “Jimmy's photos have been around a lot…One print is on the wall of my classroom, where I sometimes use it to start kids thinking about reflective writing on their own families. Occasionally there are gorgeous pieces of work. One of his great-granddaughters, still in Aberdeen, used it…as the central image of a project she was doing at school.”

The photographs capture a British army in transition. The regular and territorial soldiers, who fought in the terrible battles of 1914 and 1915, have almost all vanished. They have been replaced by Lord Kitchener's amateur volunteers of 1914 – the “Pals” and “Chums” – who fought for the first time, and died in their tens of thousands, in the Somme offensive.

There are still one or two walrus-moustached soldiers of the old school. Their faces would not have been out of place at Balaclava or Waterloo. Many of the soldiers are heart-wrenchingly young. Their faces are startlingly modern. They look like the young men that you could meet in a pub in 2016

In some images, the soldiers are wearing German ceremonial spiked helmets. The same helmets appear over and over suggesting that Mr Depire kept them as a photographic prop. In other pictures, Tommies are wearing raw sheepskins, making them look like Greek partisans or ancient warriors. There was an overcoat shortage in the bitter winter of 1915. Sheepskins were sent out to France instead.

Other pictures, judging from the foliage in Mr Dupire’s garden, were taken in the spring or summer – just before or during the “Big Push” itself.

The Somme was the most murderous single battle of the 1914-18 war. In a little less than five months, an estimated 1,200,000 British Empire, French and German soldiers were killed, captured or wounded. There were more than 400,000 British and Empire casualties, including 125,000 deaths – 21,000 on the first day alone.

As summer moved into autumn, the battlefield, still green and forested on 1 July, became a desolate landscape of smashed villages, broken tree-stumps, shell-holes, rotting bodies and mud. By mid-November, the British and French had advanced the equivalent of 77.5 metres (the length of three quarters of football field) for each day's fighting. Each metre of territory gained towards the east cost, on average, the lives of 11 British, Irish, Australian, New Zealand, Canadian and South African soldiers.

The house where most of the photographs were taken was 45 Rue d’Amiens, now 45 Rue du General Leclerc, in the village of Warloy-Baillon, eight miles behind the front lines of the Somme. The house is still there. The garden and courtyard seen in the background of many of the shots, sadly, no longer exists.

It was, according to legend, a love affair in Warloy-Baillon between a British officer and a local woman which inspired one of the great World War One popular songs, “The Roses of Picardy”. A few of the new images show French civilians,who are probably members of the photographer’s family. The two little girls who appear are believed to be the photographer’s nieces, Rose and Marguerite. Since this Rose was probably only six years old at the time, one of the young women pictured was perhaps the original “rose that dies not in Picardy…the rose that I keep in my heart!”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments