Why a crackdown on the Indian cattle trade is being criticised as anti-Muslim

A recent tightening of 'cow protection' laws in India has left Muslim cattle traders and beef consumers feeling persecuted

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the year since an extremist Hindu monk was tapped to lead one of India‘s biggest states, the country’s Muslim cattle traders have seen their lives change in ways they could not have imagined.

First mobs of Hindu vigilantes emboldened by the monk’s victory began swarming buffalo trucks on the road, intent on finding smugglers illegally transporting cows, which are sacred to the Hindu faith and protected from slaughter in many places in India. Some Muslim men were killed by lynch mobs, as recently as 18 June.

Then dozens of slaughterhouses and 50,000 meat shops were closed, severely limiting access to red meat, a staple of the Muslim community’s diet. Hundreds from the Qureshi clan, Muslims in the meat trade for centuries, lost their jobs.

Recent moves led by the Hindu nationalist party of Narendra Modi to tighten “cow protection” laws have contributed to a 15 per cent drop in India’s $4bn (£3bn) beef export industry, until recently the largest in the world, disrupting the country’s traditional livestock economy and leaving hundreds without work at a time when India needs to add jobs, not lose them.

The changes in the cattle industry mirror what’s happening nationally for many of India’s 172 million Muslims, for whom lynchings, hate speech and anti-Muslim rhetoric from a host of legislators from Modi’s party have taken a toll. In Mahaban, the Muslim cattle traders say their way of life is being slowly strangulated by the policies of a government and its allies intent on establishing Hindu supremacy.

“It’s undeniable that the last four or five years, it has become much worse for Muslims in India,” says Nazia Erum, the author of a recent book about Muslim families. “It’s okay to hate now. Hatred has been given a mainstream legitimacy.”

The government has sent a message: whatever facilities we were providing to Muslims, we’re not going to provide them anymore

Bhurra Qureshi, 40, loads the last of the buffaloes on the truck, having negotiated the terms of their passage from the village’s livestock market to the meat-processing plant in Aligarh, about two hours away.

He is happy to get $80 to transport the 14 hulking black buffaloes because his hauling business is way down. Buffaloes can be legally slaughtered in this part of India, where cows cannot, and it is buffalo meat that drives India’s beef export industry. But when he climbs into the rig, Qureshi’s mind turns to the pitfalls of the drive ahead.

There is new danger on State Highway 80, the only way to Aligarh. Once a sleepy backwater of religious pilgrims and camel carts, it has become a minefield of Hindu zealots waving bamboo sticks and police allegedly exacting hefty bribes.

“I’m always apprehensive before I start,” Qureshi says. “My wife asks me to stop driving and do something else, but I tell her I know no other work.”

Traders who run buffaloes legally – buffaloes are not revered in India as cows are – have been beaten and thrown in jail, and their animals and trucks confiscated by either Hindu activists or the police, risks that have contributed to a 30 per cent rise in transportation costs in the past year, according to Fauzan Alavi, vice president of the All India Meat and Livestock Exporters Association.

To buy “peace on the highway”, as he puts it, these middlemen are paying less to the farmers in livestock markets and charging more to the meat exporters upon delivery.

Qureshi pilots the rusty truck through the village, past its three mosques, past tiny shops, past out-of-work men on stoops, past the sherbet-orange Hindu temple. He hangs a left at the cow shelter at the end of the road, a sort of Humane Society for bovines, overflowing these days since farmers can no longer sell their old cows to smugglers because of a government crackdown and have begun turning them loose in the streets.

His first test comes at the railway junction at Bichpuri, where khaki-uniformed police stop the truck and ask: “What are you doing? Where are you taking this truck?”

To Aligarh, he tells them politely. They wave him on, but a man on a motorcycle follows the truck and exacts a small bribe.

Even as India attempts to move beyond its rigid social order of caste, critics charge that elite upper-caste Hindus, many of whom eschew meat, are increasingly imposing their vegetarian culture on a country where many eat meat and where buffalo is a cheap source of protein for Muslims and those from lower castes. Modi once derided India’s soaring meat exports as a “pink revolution”.

When Yogi Adityanath – known for his inflammatory statements about Muslims – came to power last year, he ordered slaughterhouses closed, and 50,000 meat shops also shut their doors. Some but not all of the butchers were unlicensed, part of India’s thriving informal economy.

It’s undeniable that the last four or five years, it has become much worse for Muslims in India. It’s okay to hate now. Hatred has been given a mainstream legitimacy

The move has had long-standing repercussions for the 2,200 Muslims of Mahaban, a third of whom lost their jobs. The local slaughterhouse run by the municipal council was closed, along with four meat shops. Since then, Adityanath’s government has made it harder for slaughterhouses to reopen, rescinding laws that required municipalities to run them and mandating that they be moved outside cities for hygienic reasons.

“The government has sent a message: whatever facilities we were providing to Muslims, we’re not going to provide them anymore,” said Yusuf Qureshi, president of the All India Jamiatul Quresh Action Committee, a civil society group. Adityanath’s chief spokesman defends the move, saying they were enforcing existing environmental norms mandated by the courts in 2015. He also noted that the state is modernising its 16,000 madrassas, or Islamic schools.

“Adityanath ordered a crackdown on illegal slaughterhouses, it was not an ‘anti-Muslim’ drive,” Mrityunjay Kumar, the chief spokesman, said in a statement. “There was some disruption, but then nobody can make a case for unlicensed butcher shops. After the initial hiccups, the meat business is back on track.”

But the villagers disagree, and during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, known as Ramzan in India, the traders were outraged that their evening meal did not include beef. The town butcher, Yunis Qureshi, who closed his shop last year during the crackdown, now sells fried snacks on the side of the road.

“We’ve been forced to become vegetarians!” he says.

Worse, he says, the government’s actions have deepened the divide in the village between Hindus and Muslims.

“Ever since this government has come in, I feel like people look at me and see a Muslim for the first time,” the butcher says. “They’ve shut down our businesses, changed the food we eat… Of course we’re going to feel persecuted because we’re Muslims.”

Ever since this government has come in, I feel like people look at me and see a Muslim for the first time. They’ve shut down our businesses, changed the food we eat… Of course we’re going to feel persecuted because we’re Muslims

As Bhurra Qureshi’s truck rattles through the small town of Iglas, he is glad to see that the dusty lot where the Hindu cow vigilantes normally lie in wait next to a sign that says “Yogi’s Army” – with bamboo sticks at hand, saffron scarves obscuring their faces – is empty.

“We don’t go after innocents,” Bobby Chaudhary, a leader of the vigilantes, says in a later interview. “We go in groups so there is no need to beat them. We catch them and call police.”

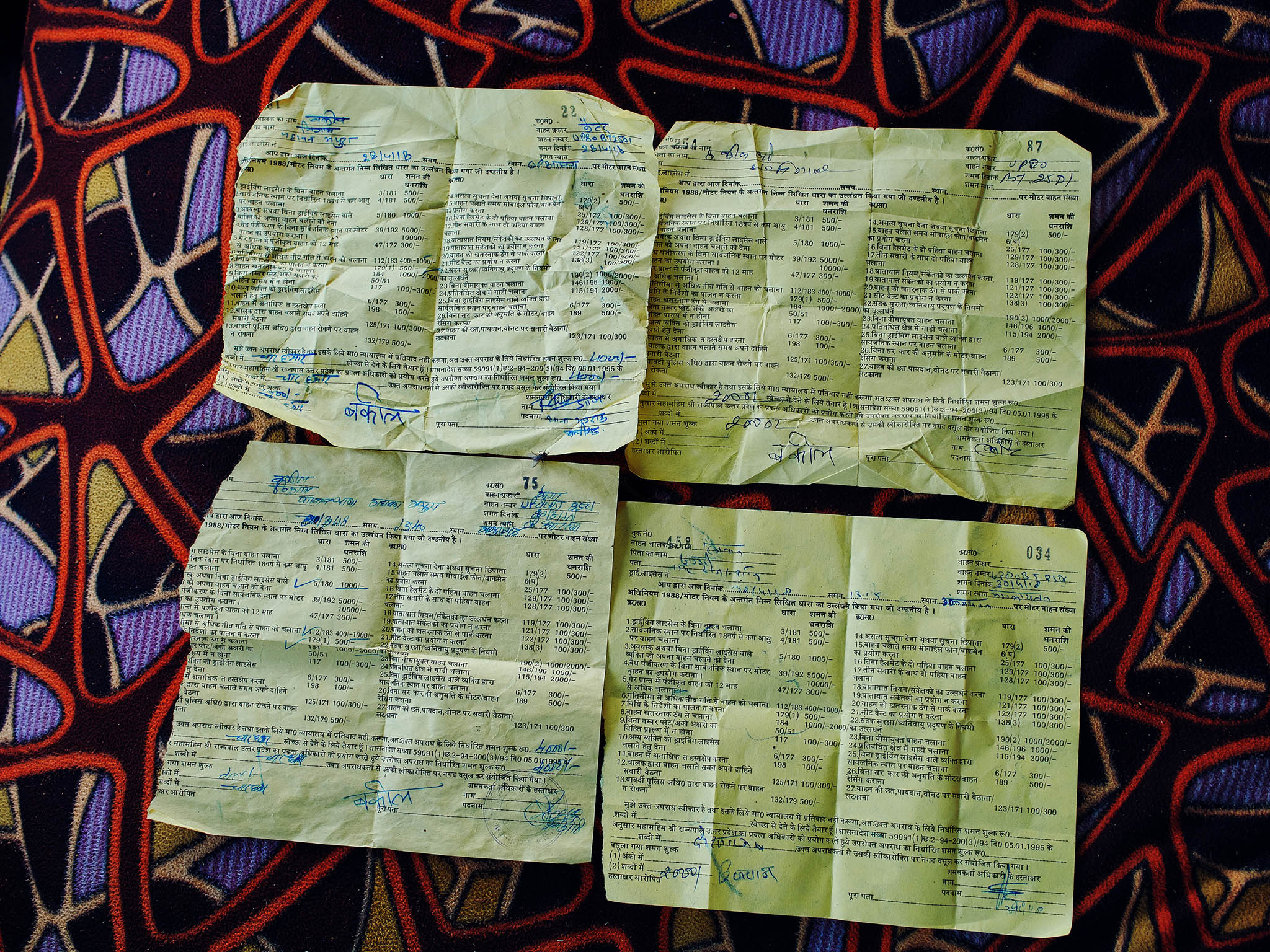

A few miles after that post comes the Aasna police station, where two dozen traders say in interviews that police officers have begun demanding bribes and beating them if they refuse to pay. Outside, officers man a barricade and wave the truckers to stop. Inside, beyond the temple dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva, an officer sits behind a desk, writing dozens of tickets.

The traders have fistfuls of these tickets for offences such as reckless driving or speeding, even though the police have no radar equipment and the closed-camera television monitor shows only the front of the station, where the trucks are already stopped. One day in May, half of the screen was obscured by a giant spider.

“We are estimating,” explains RN Tiwari, the sub-inspector in charge, who denies that he or his officers rough up the traders or ask for money above the ticketed amount.

“Everybody says we take more money, but we don’t,” Tiwari says. “Whatever tickets we cut, that is the money we take, and that goes into government coffers.”

He says police are just following state officials’ orders: “We’ve been told to cut as many tickets as possible.”

Qureshi alleges that officers attempting to negotiate a bribe recently beat him with a baton and forced him to squat like a chicken, with his arms woven through his legs and gripping his ears – a common punishment for schoolchildren. He left the station humiliated, wondering again whether he should leave this work.

Just as Qureshi approaches the city limits of Aligarh, he is stopped again and asked for cash by a state police officer parked in a black sport utility vehicle under the highway overpass. (The officer later denies taking money.)

By the time Qureshi arrives at the gates of the meat-processing plant, the temperature soars to 40C, but his face shines in relief. He had to pay only $6 in bribes this trip, which dented but didn’t wipe out his day’s pay of $80. He will drive again the next day, Qureshi says, and begins pulling the buffaloes off the truck. He is smiling as the animals lumber to their fate.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments