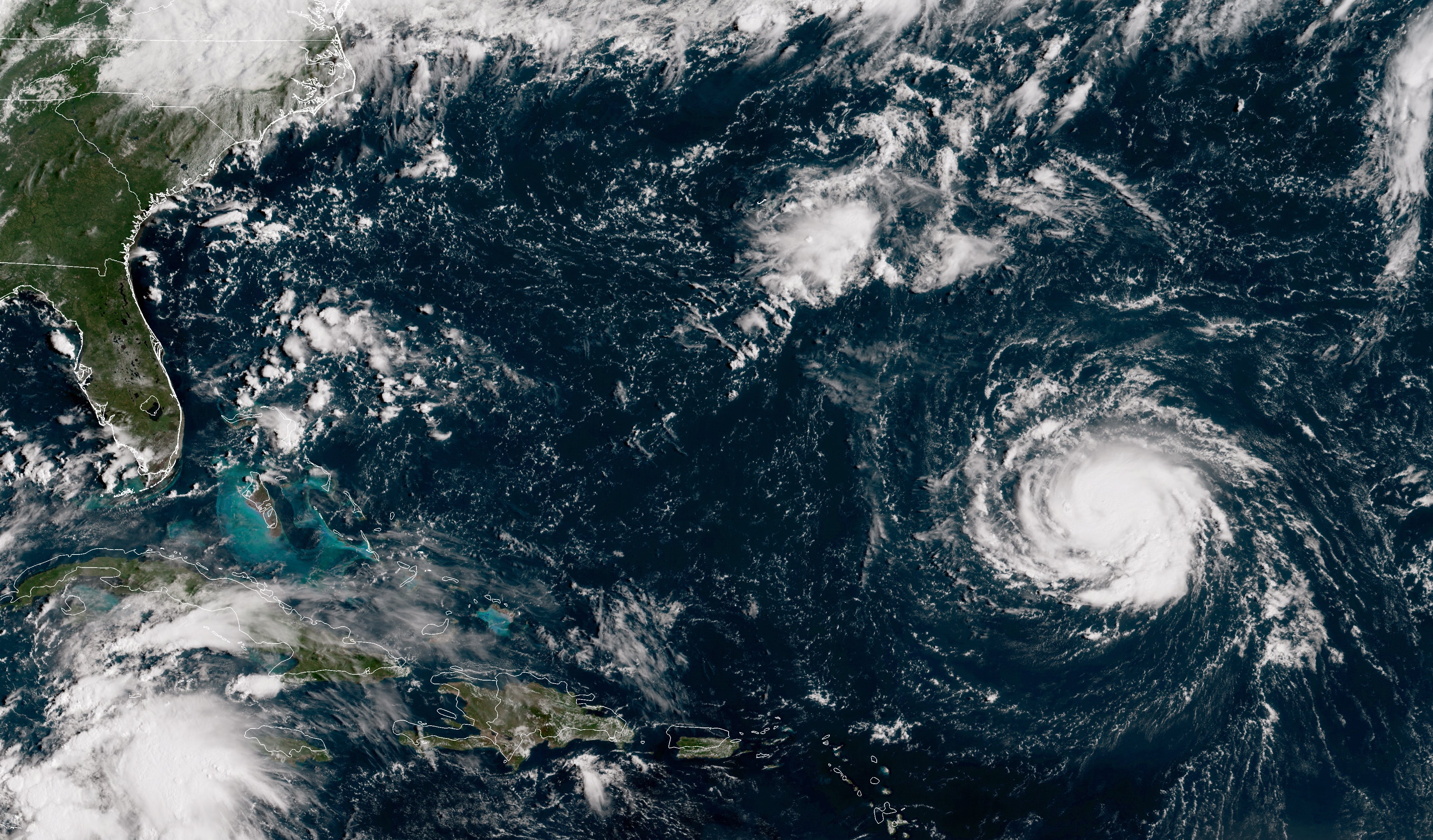

Atlantic hurricane season expected to be ‘above normal’ this year

‘An above-normal season is most likely’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Federal scientists on Thursday forecast that 2021 could see in the range of 13 to 20 named storms, six to 10 hurricanes, and three to five major hurricanes of Category 3 or higher in the Atlantic. Ben Friedman, the acting administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said, “an above-normal season is most likely.”

Hurricane season runs from 1 June until 30 November, though the past six years have seen storms form before its official start.

This year’s announcement comes after a record-shattering 2020 season of 30 named storms — so many that forecasters ran through the alphabet for only the second time and resorted to using Greek letters.

Hurricanes have become more destructive over time, in no small part because of the influences of a warming planet. Climate change is producing more powerful storms, and they dump more water because of heavier rainfall and a tendency to dawdle and meander; rising seas and slower storms can make for higher and more destructive storm surges. But humans play a part in making storm damage more expensive, as well, by continuing to build in vulnerable coastal areas.

Matthew Rosencrans, of NOAA’s climate prediction center, said “we do not expect the 2021 hurricane season to be as active” as last year’s, but added that “it only takes one dangerous storm to devastate communities and lives.” The agency will issue another forecast later in the summer, before the height of hurricane season.

Thursday’s forecast is based on NOAA’s updated “period of prediction” for storms, part of a once-per-decade revision of the statistics used to determine how a season stacks up, and reflects the growing number of storms in the Atlantic over the decades. That 30-year average number of storms has edged up from 12 named storms, six hurricanes, and three major hurricanes in the previous period’s version to 14 named storms and seven hurricanes. The number of major hurricanes has stayed the same.

The science of forecasting the effects of individual storms has seen “huge progress,” said Suzana Camargo of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. Technological advances are giving people far more accurate warnings of hurricane tracks, rainfall and surge risk as well as understanding of the connections between the storms and climate change.

The United States is approaching this hurricane season as those who respond to the nation’s disasters are stretched thin. On top of wildfires in the west, pounding rains and extensive flooding in parts of Louisiana and Texas, many areas are still struggling to recover from last year’s record hurricane season and the February freeze.

At the same time, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has diverted thousands of personnel to help run the country’s coronavirus vaccination campaign, as well as help shelter unaccompanied children crossing the southern border.

Some climate experts have argued that the annual forecast is unhelpful. Andrew Dessler, a climate scientist at Texas A&M University, groused on Twitter last year that it “is not very valuable and yields little actionable information.” He added that anyone on the Gulf or East Coast should prepare for the season, because “in any year, you have a small chance of getting hammered,” and “over a few decades, your chance of getting blasted by a big storm is pretty good.”

There is no serious scientific disagreement over whether greenhouse gases generated by human activity are causing the planet to warm, and growing agreement about some of the possible connections between that warming and storms. But there are still areas of sharp disagreement in the scientific community over some of those possible connections.

Getting the connections right is not just important for countering denialist thinking about climate change, but also to curb the tendency to overstate the science when it comes to the effects of warming. As public awareness of the risks of climate change grows, there is a tendency in the news media and among politicians to attribute every weather-related disaster to climate change, said Kerry Emanuel, a climate expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “That’s such a temptation, and it has to be resisted.”

One way that people oversimplify climate change, Ms Camargo said, is asking whether climate change “caused” a storm. That “is not the right way to frame the problem,” she said. Instead, it should be “how much has climate change contributed to this hurricane?”

So what are some of those connections?

Thomas Knutson, a climate scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has published a series of papers since 2019, including a recent review of research at the site sciencebrief.org that underscores the links with the strongest evidence. Those researchers acknowledged that a warming world is likely fueling more powerful tropical storms and contributing to increased flooding because of rising sea levels. The scientists also stated that rainfall in tropical storms is likely to increase, since a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture. The team also suggested that the proportion of severe storms has increased, though the overall number of storms worldwide has stayed about the same.

“We’re seeing a rise in the proportion of hurricanes that reach major hurricane status, Category 3 and above,” Ms Emanuel said. “That’s what we’re unequivocally seeing in the satellite data.”

James Kossin, also with NOAA, has done research lending further support to the idea that hurricanes are getting more powerful. With continued warming, he suggested, “you’ll start to see intensities like you’ve never seen before,” even storms packing 250-mph winds. (Major hurricanes, beginning with Category 3, have wind speeds between 111-129 mph. A Category 5 storm, the most powerful classification, is 157 mph and above.) “It’s only a matter of time,” he said.

The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments