The under-30s are poorer than ever – and despite all the studies it's hard to figure out why

In the UK it is quite true that young people have seen the sharpest fall in their incomes, which are lower on average than they were 15 years ago. This is partly because of the rise of the unpaid internship – nowadays, these often take the place of entry level jobs

The story seems an obvious one. We are not building enough houses in the UK, particularly in London and the home counties to match the rising population. So prices are rising relative to incomes. This is particularly hard on the young, who are also seeing their incomes squeezed by low pay and for many, the burden of student debts. As a result overall home ownership is falling and is now the lowest for 29 years. And the proportion of young people owning homes is falling fastest, for among 25-34 year olds, the rate of home ownership fell from 59 per cent in 2003 to 37 per cent in 2015.

That, simplified a bit, is the thesis of the Redfern Review, a Labour-backed study led by Pete Redfern, chief executive of Taylor Wimpey, the construction company. The solution, simplified even more, is an independent commission to oversee a big boost to house-building, to be sustained over the next 20 years.

John Healey, the Labour MP who commissioned the review, puts a political spin on it.

“The shrinking opportunity for young people on ordinary incomes to own a home is at the centre of the growing gulf between housing haves and housing have-nots,” he said. “Housing is at the heart of widening wealth inequality in our country.”

Actually, it’s not as simple as that, for there are three separate things happening: the general retreat of owner-occupation, the surge in asset inflation, and the shift in incomes between young and old. And pretty much the same trends are evident everywhere in the developed world.

Start with the retreat from owner-occupation. Some 63 per cent of our homes are owner-occupied, down from a peak of 69 per cent in 2001, and we are indeed back to the level of the middle 1980s. But this isn’t just a British phenomenon. Owner-occupation is falling right across Europe, and in the US too. Within the EU the peak was in 2009 at over 73 per cent, and it is down to 69 per cent this year. In the US the peak was in 2007, at 69 per cent, and now at just below 63 per cent it is the same level as it was in the 1960s.

Why is it falling, and why particularly among the young? Well, part of the problem must be affordability, but it can’t just be that. The European country with the lowest house price levels relative to income, Germany, also has the second-lowest levels of owner-occupation, 52 per cent. Only Switzerland is lower.

In the UK the sharp rise in renting over the past five years may well be associated with the rise in immigration from Europe, with young people coming here for jobs but not wanting to take on the responsibility of buying a home in a foreign country. In the US it may also have something to do with the rising mobility of the young, moving to the coasts for jobs, but again not being sure they will stay there.

Again, this change may also be connected to other social changes, such as starting families later, the rise in self-employment, more fluid choice of partner, and so on.

Next, asset inflation. One of the charges against the world’s central banks is that ultra-cheap money has widened wealth inequality by boosting asset prices. It’s hard to deny that this is the case, for the more assets that people have the more they will have benefited. But the impact on property has been uneven. So Stockholm and Berlin join London and New York in seeing a surge in homes’ prices. But in less sought-after areas, even in the UK, prices are still well below their 2007 peak.

What must be pretty much beyond question is that where there is rising demand for homes, those homes should be built. Any blockages that a new property commission might be able to clear would be most welcome, for the problem seems to be one of lack of supply rather than lack of finance. Here in the UK there are no less than eight different government-supported schemes to get more money into housing.

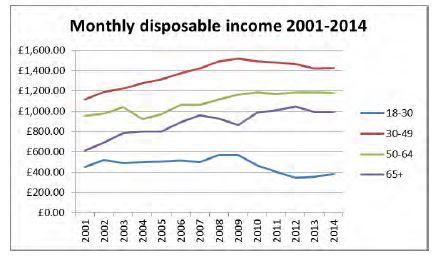

And the shift of income away from the young? In the UK it is quite true that 18-30 year-olds have seen the sharpest fall in their incomes, which are lower on average than they were 15 years ago. This is partly because of the rise of the unpaid internship – nowadays, these often take the place of entry level jobs, which in turn drags down the wages paid for each strata of job above. Thus, even when they progress into mid-level jobs, this age group are making far less than their peers a decade older than them who embarked on the career ladder at a time when they weren’t expected to initially work for free.

True, too, that over-50s have done best, though in absolute terms they have lower incomes than 30 to 49 year-olds. But you have to compare like with like. There are more young people in higher education and fewer in full-time work than 15 years ago, and more people over 65 still working. The need for IT skills ought to be favouring the young and it is not clear why this is not happening.

Maybe inward migration from Europe has had some impact, but that is not clear. Amid this great puzzle, however, there is one point of clarity. We need to build more homes.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments