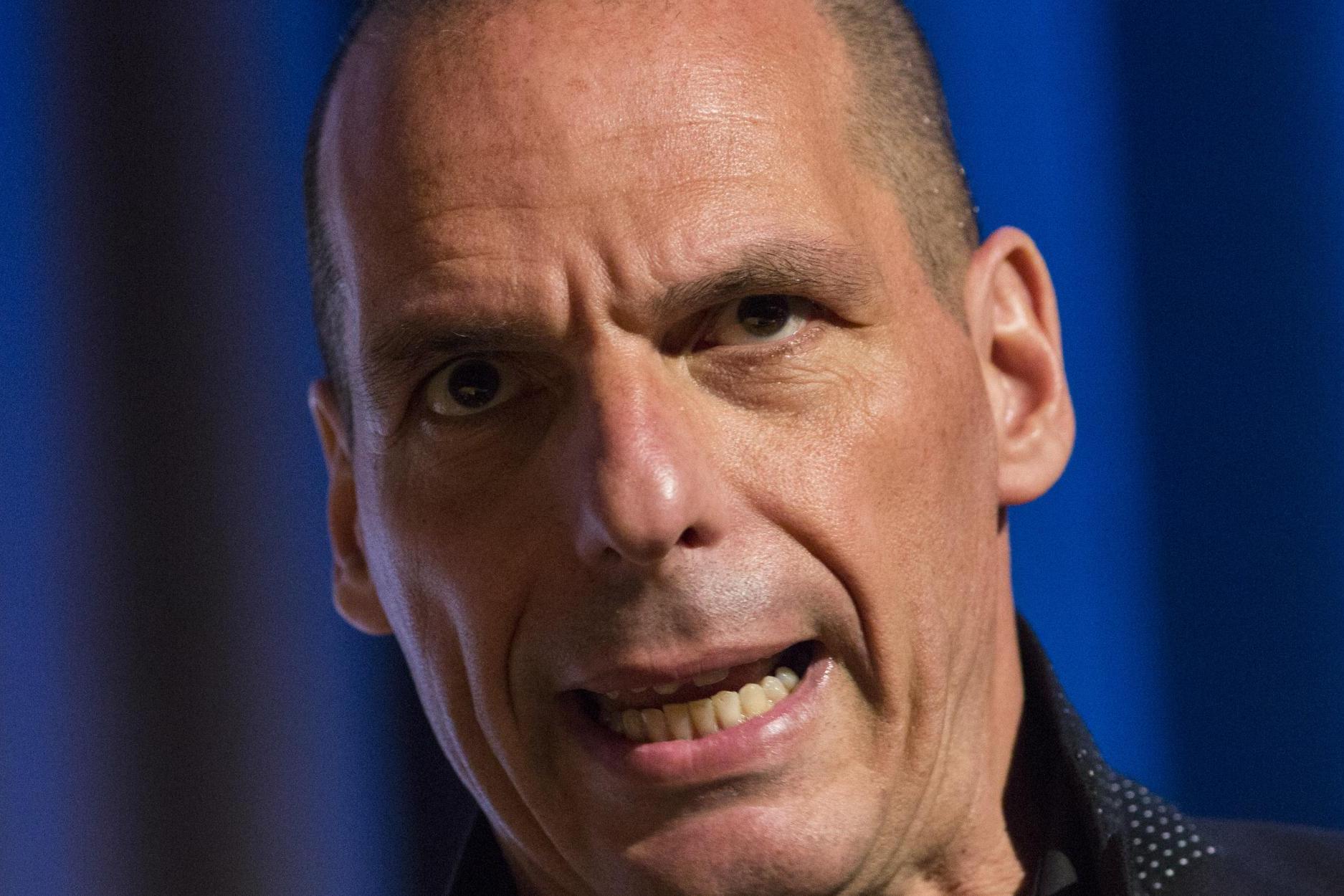

Yanis Varoufakis’s argument that there is a ‘Marxist’ case for staying in the EU isn’t as simple as it seems

In the abstract, the transnationality of the single market fits with left-wing ideals. But let's look at the reality. Every mass social movement that has laid a national democratic challenge has found itself confronted by the infrastructure of the EU

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“It was fantastic to hear a key figure from the European left making the inspirational case for keeping Britain in the single market as the best means post Brexit of advancing social justice and progressive values.”

Those the words of Chuka Umunna at a meeting of the Open Britain campaign as he heaped praise on Yanis Varoufakis as part of a shared commitment to shift the Labour position towards single market membership.

Varoufakis has offered a devastating critique of the EU leadership and their commitment to protect their own institutions at the cost of sovereign nation states like Greece. In his book Adults In The Room he couldn't be more blunt: “Greece was merely the laboratory where these failed policies were being tested and developed before their implementation everywhere across Europe.” The “adults” in the title represent Varoufakis’ desperate hope that EU officials would consent to a just solution to the Greek debt crisis. They didn't.

Despite his own battles with the establishment, in his speech this week he put forward a Marxist argument for the UK to remain in the single market. “I will speak as a Marxist. Communist Manifesto: when he says that the communists are being blamed or accused of wanting to take nationality, ethnicity, national pride away from the majority. And he says ‘you cannot take away from them that which they don’t have’. There is a very good leftist, Marxist argument in favour of the transnationality which the single market, and indeed the European Union, is putting forward.”

As Varoufakis knows all too well, charting a course forward is not easy. But we have to ask ourselves if structures like the single market aid or curtail the fundamental social and economic transformation that is needed. And, does his acceptance of EU institutions correspond to a viable strategy for European progress?

Under single market rules, services are wide open to privatisation. Take the railways. We are told that it is perfectly possible to nationalise rail while retaining membership of the single market. The truth is more complicated.

According to the Fourth EU Package of Rail Liberalisation Directives, all EU states will have their rail networks opened up to competition by December 2019. This means that running a fully-fledged public monopoly that would operate all aspects of the railways in the vein of British Rail is not possible as competition is preserved. This is just a glimpse of a wider framework that compels towards privatisation.

For example, State Aid rules in relation to National Investment Banks mean the ability of the state to implement a serious programme of national economic planning is limited, thus providing yet more fertile conditions for private companies to take over services. If a radical government wanted to deploy the funds of a National Investment Bank to reorientate the economy by rebuilding industries, it would have to overcome the array of rules that implant competition into the process – and would need to be signed off by the European Commission itself. In short, the rules are stacked against any government who wants to challenge the logic of the market.

Come what may, the present European economic apparatus is going to have to be confronted. Varoufakis argues in his Open Britain speech in the context of the transnationality of the single market: “...we must also preserve Britain’s presence in European politics, and in the progressive movements in Europe that are necessary to make the European Union sustainable and democratic. And vice versa.”

In the abstract this seems sensible. But let's look at the reality. Every mass social movement that has laid a national democratic challenge has found itself confronted by the infrastructure of the EU. The people of Greece, Catalonia and Ireland, far from seeing their struggles internationalised, have been met with militant hostility by the institutions. Indeed, had the Greek leadership taken the mandate of the people over that of the EU – the entire European Left would be stronger today. Varoufakis' strategy on this has already been tried and tested, and it failed.

Even Varoufakis is not confident about the balance of forces in Europe. He says: “My great fear is that the fragmentation of this already highly undemocratic EU is not going to bring us more national democracy, or improve our circumstances economically, but that the opposite will happen which will only aid the ultra-nationalists and those who invest in division.”

Indeed, the EU is the crucible of this resented order. The reorganisation of European fascism in the form of the French National Front or the Austrian Freedom Party was accelerated by the 2008 crash which married financial corruption with alienation from official politics.

The rhetoric of the new right also centres on a distinctly pan-European racial identity. In this it mirrors the essential policy of the EU, which recognises internal migration but shuns racial others. Fortress Europe has the hardest of all borders through the Mediterranean Sea. The far-right draw their ideological legitimacy from this regime – they are not beaten back by it.

There is no reset button that can erase the deep social processes that are now at play. I share Varoufakis' concerns for the future of European society. But we need a broader debate about the way forward – one that goes beyond trying to “save the EU from itself.”

Jonathon Shafi is a Glasgow-based activist who writes on international politics for a range of outlets. He is a co-founder of New Foreign Policy, a recently formed think tank.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments