No more empty apologies for Windrush. Britain has to face the ugly truth about empire, starting with education

No one should be delivering immigration policy without a thorough knowledge of what came before. But it’s not just the government, we need to reform the curriculum, writes Kimberly McIntosh

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The long-awaited Windrush Lessons Learned Review, published on Thursday this week, opens with the story of Nathaniel. Nathaniel went on holiday to Jamaica with his daughter in 2001. When they tried to return to the UK, immigration authorities told him he could not come back in.

His passport of 45 years was no longer valid, though it had been when he took a trip to Jamaica in 1985. He had arrived in Britain as a citizen of the UK and Colonies in the 1950s. In 2010, he died in Jamaica of prostate cancer. He could not afford treatment. Nathaniel had every right to be in Britain, so why was his re-entry denied?

Nathaniel was one of the 160 people, mostly of Caribbean descent, who were erroneously detained or deported in what would become known as the Windrush scandal. Up to 8,000 have been caught up in the scandal in myriad ways, suffering great injustice as a result; people made destitute, separated from their families, losing their jobs, homes and identity.

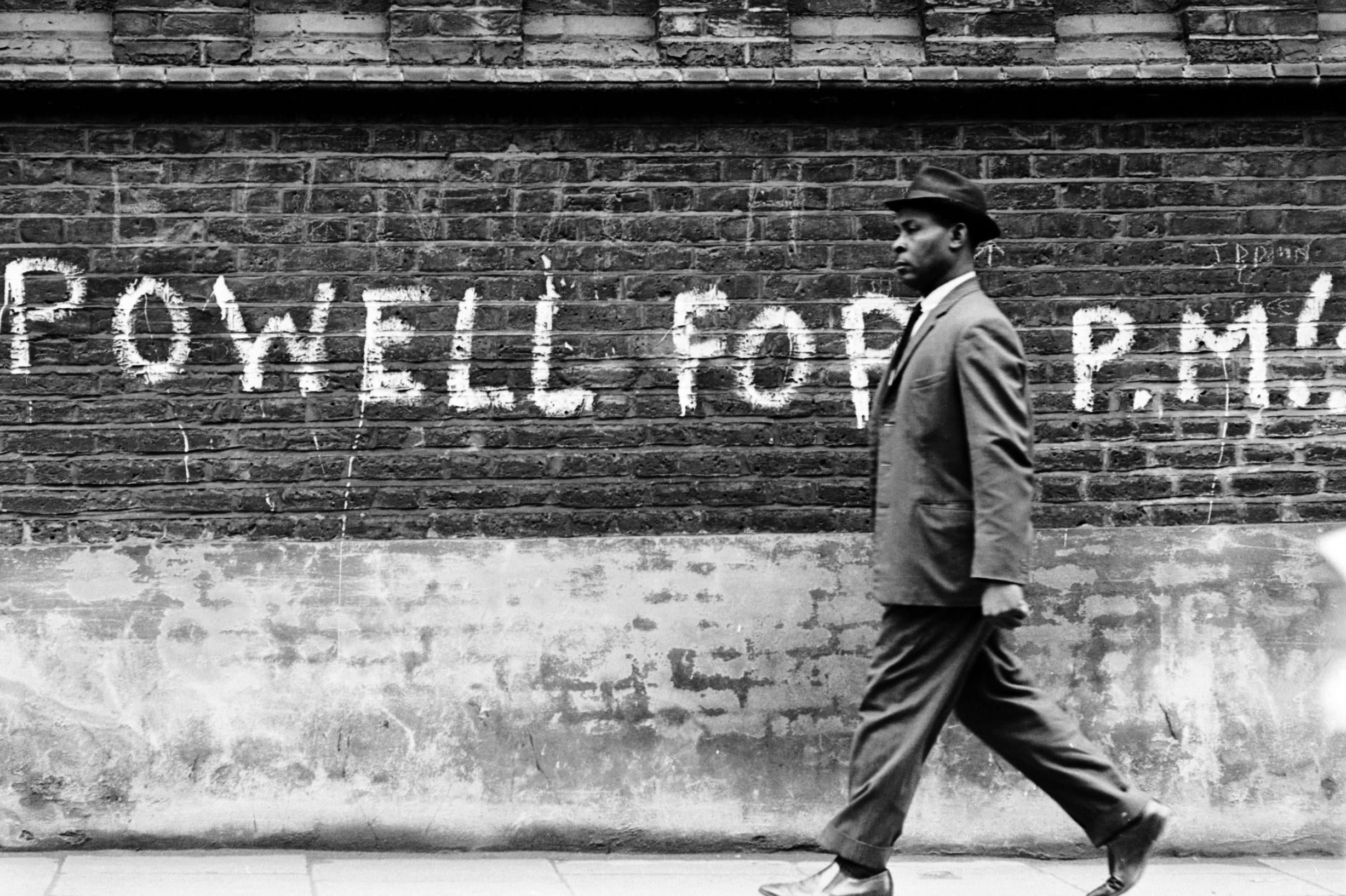

Nathaniel moved from the Caribbean to the UK as a citizen, when his birth “country” was still part of the British Empire. Because of this, many people from the Caribbean, including my grandmother, arrived on British passports. Others, like my aunts, arrived later on their parents’ passports. They lived, worked and had families without the need for documents. But new immigration laws in 2014 and 2016 forced individuals to prove their status to access basic public services, rent housing or start a new job.

Wendy Williams, author of the Lessons Learned review, found that a lack of understanding of this history by Home Office staff and successive governments was a root cause of the Windrush scandal, calling it “institutional ignorance and thoughtlessness towards the issue of race and the history of the Windrush generation”.

The comprehensive report shows us how immigration legislation in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s made it harder for people of colour to move to the UK and laid the architecture for the scandal. Commonwealth citizens who moved to the UK before 1973 were entitled to stay and didn’t need to prove it. They had the option to register before 1987 – but the government’s own publicity at the time said there would be “no consequences” if they didn’t.

But when the scandal began to get public attention in 2018, the report found the Home Office blamed individuals for “failing to obtain evidence of their status”. If Home Office staff and politicians had understood both past policy and how Britain’s history is tied to the Caribbean then the scandal could have been avoided.

One of the recommendations of the review is for all Home Office staff to undergo comprehensive training drawn up by academic experts about the history of the UK and its relationship with the rest of the world, including Britain’s colonial history and migration.

Williams urges the Home Office and the government “to tell the stories of empire, Windrush and their legacy”. She’s right. No one should be working on or delivering immigration policy without a thorough knowledge of what came before. But it’s not just policymakers that need to understand this history. The best way to “tell the stories of empire, Windrush and its legacy”, and as a consequence, a fuller version of our national story, is by reforming the curriculum.

Under the national curriculum, students are meant to learn about “how Britain has influenced, and been influenced by the wider world”. Last year, a report from Runnymede Trust with the TIDE project and Dr Jason Todd – Teaching Migration, Empire and Belonging – found that the number of schools teaching migration, belonging, and empire is unknown.

They appear as “suggested topics” but the colonisation of the Caribbean and the end of the empire don’t feature even as suggestions. Our Migration Story, an education resource covering migration in Britain from the Romans to the 21st century, attempts to address this – but more is needed, such as government backing for over-stretched teachers to be provided with training and development.

This is not the first time this has been a recommendation in a government review. Over 20 years ago, Lord Macpherson’s inquiry into the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence made a similar suggestion. It said the national curriculum should be revised “to prevent racism and value cultural diversity.”

The government shouldn’t wait another 20 years to take action. The announcement of a £500,000 fund for grassroots organisations that run advice surgeries and support people applying for compensation is welcome and long overdue. And their commitment to launch a Windrush working group to develop programmes of support for those affected by the scandal is positive, if vague.

But so far, the government has been quicker to apportion blame to political parties of all shades and reiterate that “successive governments” are at fault, instead of committing to concrete actions. They have only committed to “reflect” on the recommendations to change the Home Office “target” culture that discourages common-sense decision-making. There is no mention of a review into the hostile environment and its impact.

The Windrush Scandal is far from over. People are still homeless, facing unemployment and fighting deportation. The mental health impact is incalculable. The pointing of fingers by the government and claiming “you started it” will not achieve justice.

Agreeing to enact all of the recommendations in the Lessons Learned Review would be a start.

Kimberly McIntosh is a senior policy officer at the Runnymede Trust and at the research organisation Race on the Agenda

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments