The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Some of the most interesting Windrush passengers were Indo-Caribbean – yet their stories remain untold

On Windrush Day, the story of Caribbeans of Indian descent aboard the eponymous ship is not a straightforward history to trace or tell

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Lynda Mahabir won her immigration case in court last month, it was a victory for all Windrush campaigners. However, it also drew attention to a less visible group, the Indo-Caribbean members of the Windrush generation. The UK census has no classification for “Indo-Caribbean” as it does “Black Caribbean”, therefore exact numbers are unavailable. The closest census designation is “Asian Other”, which counted 835,720 people. According to the National Archives, “by the end of 1990, the British Indo-Caribbean population was estimated at between 22,800 to 30,400”.

The Indo-Windrush story is not a straightforward history to trace or tell; it is as ethnically composite as the Caribbean region itself. Stuart Hall, the influential Windrush-era intellectual, arriving at Oxford from Jamaica in 1951, listed “East Indian” among the ethnicities in his own family background. But one thing is certain: if Indo-Caribbeans are here now, they must have been there then, aboard that very ship, HMT Empire Windrush, that has become symbolic of postwar Caribbean migration to the UK.

I count 12 surnames of confirmed South Asian origin on the Empire Windrush’s passenger list (and just as many of East Asian extraction): Gopthal, Julumsingh, Luckhoo, Maharaj, Maragh, Mohamed, Mohan, Singh, Sukhram, Susayat, Tingling, and Remachandan. In addition, there are other surnames that resonate etymologically with the Indian subcontinent.

The bearers of these names were natives of British Guiana (now Guyana), Jamaica, and Trinidad, progeny of the over half-million indentured labourers transported to the Caribbean from India between 1838 and 1917. Young and yearning, they transformed both Britain and the Commonwealth. I spoke to some of their descendants.

Aladdin Tingling Diakun, 37, a Canadian lawyer, remembers his Grandpa Eggie with deepest love and respect. “He lived an extraordinary, challenging, and richly rewarding life across Jamaica, Wales and Canada”, Diakun told me.

Egbert Tingling (1926 to 2005) was passenger number 891 aboard the Windrush. He was 22 at the time, from Sav-la-Mar, Jamaica, he had served in the war. “He had a very melodic voice and got offered a job to train as, and become, a broadcaster” in Wales, said Helen-Claire Tingling, Egbert’s Welsh-born daughter. Standing 5 feet 4 inches, what Mr Tingling lacked in height he possessed in determination and generosity. He raised 10 children with Icilda (née Byfield), his Afro-Jamaican-Macedonian-Welsh wife of 40 years, battling unrelenting discrimination in employment, housing and the education system. From doing menial labour in London after the broadcasting job terminated, he rose to a position as an industrial chemist before emigrating with his family in 1970 to Jamaica, then Canada.

“He is representative of an entire generation who weren’t given the opportunities that others had because of the colour of their skin, so they had to make their own way,” Ms Tingling said. “And that meant that they weren’t afraid of starting again.”

Sikarum Gopthal, 28, also from Jamaica, passenger 664, declared his profession as “mechanic”, but worked as a tailor in London, according to later records. He rented a place at 108 Cambridge Road in NW6, where, in 1952, he was joined by his son from Jamaica, Leichman, Lee for short. Entrepreneurial Lee became an accountant and ended up purchasing the Cambridge Road building. There, in 1968, Lee Gopthal founded Trojan Records, the iconic British record label that introduced reggae music to the UK and European markets.

Bhola Maharaj, from Trinidad, passenger 472, was 24 and stated his occupation as “chauffeur”, and his destination “Yorkshire”. He adopted the anglicised surname of Mansfield and continued driving professionally. In the 1983 New Year Honours list, Bhola Maharaj Mansfield was bestowed a British Empire Medal (BEM) for his service as a “driver/loader” for Manchester City Council’s Refuse Collection Service.

Indo-Windrushers are not dissimilar to their Afro-Caribbean shipmates in that many of their paper trails go dim or totally dark after Tilbury docks. To find them, we sometimes have to read between the lines of what others have written about the era.

Take passenger 466, Kadir Mohamed, 27, from British Guiana. He put down “104 Inverness Terrace W2” as his “proposed address in the United Kingdom”. This address is a short 12-minute walk to the corner of Chepstow Road and Westbourne Grove, the intersection from which the literary character Moses Aloetta sets off by bus to Waterloo Station to greet a new arrival from the Caribbean in The Lonely Londoners (1956), one of the first novels about the Windrush generation, authored by Sam Selvon, himself an Indo-Trinidadian. If we cannot locate Mohamed in the archive, we can always follow Moses.

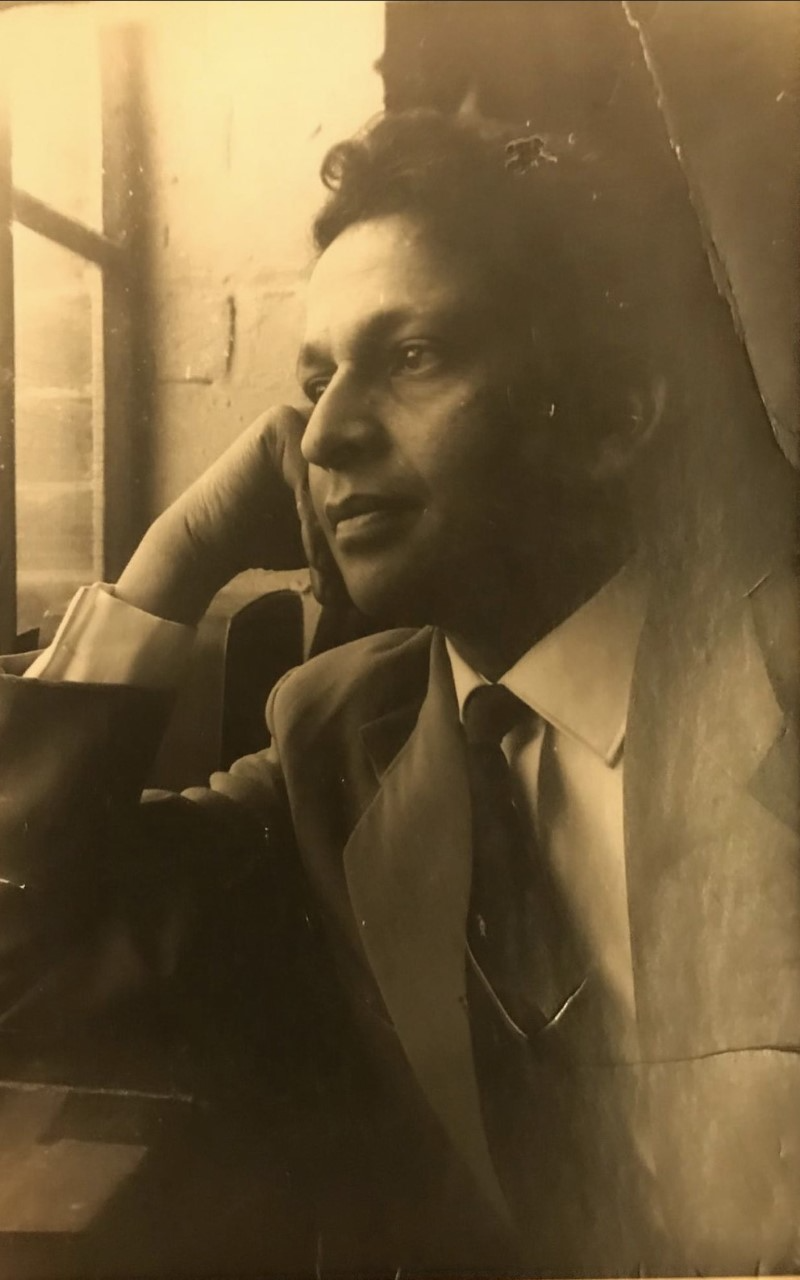

K Remachandan, 24, from Jamaica, passenger 831, gave only his first initial and no address in England. Without a place to sleep, he would have been eligible for a bed at six shillings, sixpence a week in the former air raid shelter beneath Clapham Common that was set up to lodge Windrush passengers needing a roof over their heads. Is that him to the far left, wearing a v-neck sleeveless sweater and pleated trousers in this photograph?

The most infamous Indo-Caribbean Windrush passenger was among the most privileged, number 489, Dalip Singh. He was 26 and headed to medical school at University of Edinburgh. He would successfully qualify as a doctor, marry a refugee from Nazi Germany named Inge Brown, herself an optician, and return with her to live and practice in his native Trinidad. In 1955, following a widely publicised trial covered by newspapers as far afield as London, Delhi, and New York, Dr Singh was convicted of murdering his wife, and hanged. The trial inspired the Trinidadian-American author Elizabeth Nunez to pen the novel Bruised Hibiscus (2000).

In his retirement, Egbert Tingling took up yachting, becoming the self-titled “first black commodore of a Canadian yacht club”. But his children and grandchildren never knew he also sailed on the Empire Windrush. “Ed Williams and Glen Douglas were two of his old friends”, Helen-Claire said. “I don’t know if they were also on that ship, if he knew them from that time.”

Her intuition was spot on. Edgerton Williams, then 21, was passenger number 916, and Glen Douglas, 28, passenger 625. Egbert Tingling had maintained a lifelong bond with his shipmates.

Nicholas Boston, PhD, is associate professor of media sociology at Lehman College of the City University of New York

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments