Why is Osborne so keen to balance the budget? To bring about a smaller state

The Chancellor will say that there is no alternative to his plan if the Government’s finances are to be put in order but you will search in vain for any serious economic support for that argument

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is risky to predict what’s going to appear in a Chancellor’s fiscal package, particularly when the Chancellor in question is a surprise-merchant like George Osborne. But one thing of which we can be reasonably confident is that Mr Osborne will unveil a contraction in the scope of the British state of historic proportions on Wednesday.

Why, though? Why do we need yet more austerity? “To tackle the deficit” will be the Chancellor’s answer. In 2014-15 the Government spent £738bn but took in only £648bn in tax receipts. To make up the difference the Treasury was forced to borrow £90bn, equivalent to around 5 per cent of GDP. The Chancellor has said he wants to turn this budget deficit into a surplus by 2019-20. And he’s decided to make that happen, primarily, by squeezing state spending.

To look at the headline numbers, this squeeze might not look that severe. In cash terms, total public spending is actually expected to rise to £804bn. Adjusted for expected inflation, spending will be more or less flat for five years. And as a share of GDP, total spending is only forecast to decline by four percentage points, from 40 per cent to around 36 per cent.

But this doesn’t factor in other powerful upward, mainly demographic, pressures on state spending. State pension outlays will rise steadily over the coming years thanks to the Government’s generous “triple lock” on the payment. Spending on the National Health Service, whose budget has been protected in real terms by the Government, will also grow as it is forced to cater for a more elderly population with more complex health problems. And like a couple of giant hogs at the feeding trough, those two animals will barge most of the smaller beasts out of the way.

That is why Whitehall departments after the May general election were instructed by the Treasury to sketch out potential budget savings of between 25 and 40 per cent to be achieved over the next four years.

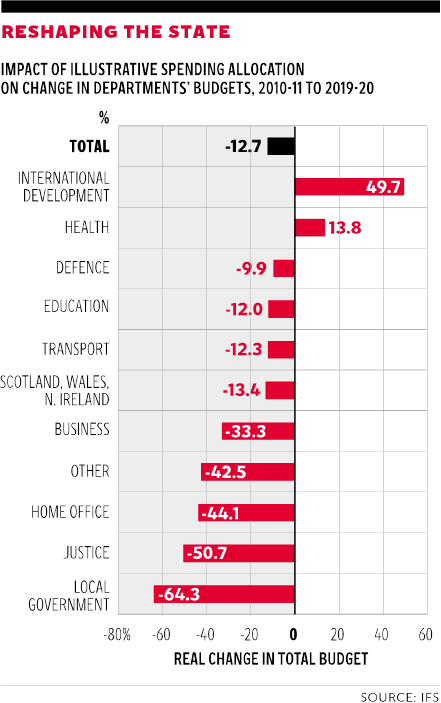

This will have profound implications for the functions of the British state. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has modelled the size of the potential cuts faced by Whitehall departments, and the results are eye-popping. The IFS thinks local government could be looking at a 27 per cent cut over the next five years. The Home Office might have to swallow a 26 per cent budget reduction. Justice would take a 25 per cent hit, and the Business Department’s annual spending would be 18 per cent lower.

And this is on top of the deep cuts in the last parliament. Factor those in, and by 2019-20 Home Office spending could be 44 per cent lower in real terms than a decade earlier. The Business budget could be a third lower. And local government’s central grant could be an incredible 64 per cent smaller. Total spending on public services would fall to below 24 per cent of GDP. Only briefly twice since the Second World War has it been that low.

The Chancellor may loosen the spending squeeze slightly by pushing out the date of the targeted surplus. He did so in the July Budget, partly out of a fear of appearing too extreme. Yet the broad parameters of this severe public sector austerity picture are likely to remain in place. And Mr Osborne may even try to ease the impact of his deeply unpopular tax credit cuts by taking an even bigger bite out of some department budgets.

The Chancellor will say, as he always does, that there is no alternative to his plan if the Government’s finances are to be put in order. Yet you will search in vain for any serious economic support for that argument. The vast majority of public finance experts agree that there is no imperative to run an absolute budget surplus at all; most think it would be sensible, instead, to commit to running a surplus only on the current budget (which means excluding capital investment, which boosts the productive capacity of the wider economy). Indeed, that was something that Mr Osborne himself thought was sensible in the previous parliament. His original self-imposed fiscal mandate required a surplus on the current budget, not an absolute surplus.

A new target for current budget surplus in 2019-20 would widen the spending envelope for that year by around £30bn, reducing the required squeeze on Whitehall departments by a similar amount. Indeed, such a recalibration would more or less remove the need for any additional spending cuts set to be imposed on unprotected departments over the next four years. Let’s be clear: these extra cuts are made necessary only by the Chancellor’s obsession with targeting an absolute surplus.

But doesn’t running a deficit mean the national debt will inevitably continue growing? That’s true only in cash terms. The relevant measure of the national debt is its value as a share of GDP. And a modest absolute fiscal deficit, even in perpetuity, is perfectly compatible with a declining national debt as a share of GDP.

A few months ago Lord Turnbull, who was the country’s most senior civil servant for a period under Tony Blair, suggested to Mr Osborne in a parliamentary hearing that despite all the Chancellor’s rhetoric about the evils of the national debt, his true objective was achieving a smaller state. He put it to Mr Osborne that he simply wants Whitehall and most public agencies to do and spend less.

That’s certainly consistent with Mr Osborne’s behaviour since he became Chancellor. Think of the front-loaded austerity in 2010 when the economy was weak and many urged caution, the replacement of his fiscal mandate with something still more austere when the economy finally improved, the animosity to the idea of a (genuine) state-owned investment bank. Think of the hyperactive privatisation programme. And for all its trumpeting of a Northern Powerhouse and new high-speed rail links, the Treasury has pencilled in net public capital spending to fall to a measly 1.5 per cent of GDP by the end of this parliament.

Yet the curious thing is that the Chancellor clearly feels shy of making a clear economic argument for a smaller state. This suggests he calculates that his agenda is not particularly popular, and that the only way to get the public to swallow it is to present people with dubious scare stories about the size of the national debt.

Don’t expect that cynical approach to change on Wednesday.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments