Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How do high-street banks make money? Open an economics textbook and it will inform you that they borrow at one rate from their depositors and lend at another (higher) rate to borrowers. The profits are the difference, or “spread”, between the two rates.

They used to talk about the “3-6-3 rule” for bank managers. Pay 3 per cent on deposits, charge 6 per cent on loans, and be on the golf course by 3pm. It was a simple, and profitable, life.

Yet today the spread is only part of the story. A considerable proportion of the profits of today’s high-street banks actually come from milking a minority of their less disciplined and savvy customers.

Dip into your overdraft and you will be hit by hefty charges. Do it often enough and you’ll end up bleeding money from your “free” current account. According to the Office of Fair Trading, such charges brought in around £2bn for the high-street banks in 2011. That’s out of total profits of £9bn.

Energy suppliers do something similar. People don’t tend to exercise their right to switch tariffs at the end of a fixed contract and so end up being automatically transferred on to the supplier’s more expensive “standard variable” tariff. This is a big source of profits for the big six providers.

If people behaved like the rational agents found in economic textbooks, this wouldn’t happen. We would all be sensitive to price differentials and switch energy providers or banks to take advantage of the cheapest rates and the lowest charges.

But we don’t. Studies suggest heavy overdraft users could save an average of £260 a year by switching bank. Yet even with the introduction of simpler switching, only 3 per cent of us have done so in the past year. People are still more likely to leave their spouses than their banks.

And a quarter of a century after the privatisation of the energy industry, switching rates are also still dismally low. Seventy per cent of customers languish on the relatively expensive standard variable plans of the big six providers, even though they could almost certainly get a cheaper rate elsewhere.

Large companies such as these exploit customer inertia to make profits. But why are people so inert? Psychology offers an explanation. Switching bank or energy provider requires more thought than changing, say, supermarkets. It requires a calculation of one’s likely future overdraft usage or the household’s energy needs. It involves grappling with jargon such as “EAR variable” and “kWh”. Faced with a choice where the impact on their finances seems uncertain, studies show that people often stick with what they already have. This is known as the “status quo bias”.

“Loss aversion” also comes into play. The possibility of financial loss from making a bad switch based on a faulty calculation looms larger in the mind than the possibility of gains from making a good one. Low public trust in the industries is also a contributory factor. Anyone who has ever tried to get a bank or energy firm to rectify a mistake is likely to bear the scars. Is a switch that could go wrong really worth that potential hassle?

This market failure has been noticed. The competition authorities were instructed to scrutinise both the energy industry and the high-street banks that benefit from this failure. One proposal was that the heavily concentrated structure of these markets was at the root of the problem and these large corporations should be split up to generate more customer-friendly competition.

Yet the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) recently rejected this, ruling that the solution both for energy and banking lies in tinkering rather than major surgery. The solution to customer inertia is, apparently, the provision of more information, more choice, from existing providers. But is it?

A study by behavioural economists of jam sales showed that people bought more when faced with a far smaller range of products. Too much choice sometimes seems to cause our brains to freeze up. More energy tariffs to choose from could actually result in greater inertia and less switching.

Nevertheless, the regulators are blowing with the political wind. There seems to be an assumption that the market inefficiencies should be countered with incremental “nudge” policies. This means innovations such as automatic enrolment for employees in company pension schemes and getting job centre staff to send personalised text messages to the unemployed to encourage them to take up work. The Cabinet Office has a Behavioural Insights Team, known as the “nudge unit”, which is supposed to apply this kind of innovative thing across Whitehall.

There is much to commend in this agenda, but it tends to be conservative in its approach. Structural reforms such as breaking up the dominant high-street banks and banning the vertical integration of energy providers seem to be excluded from the menu.

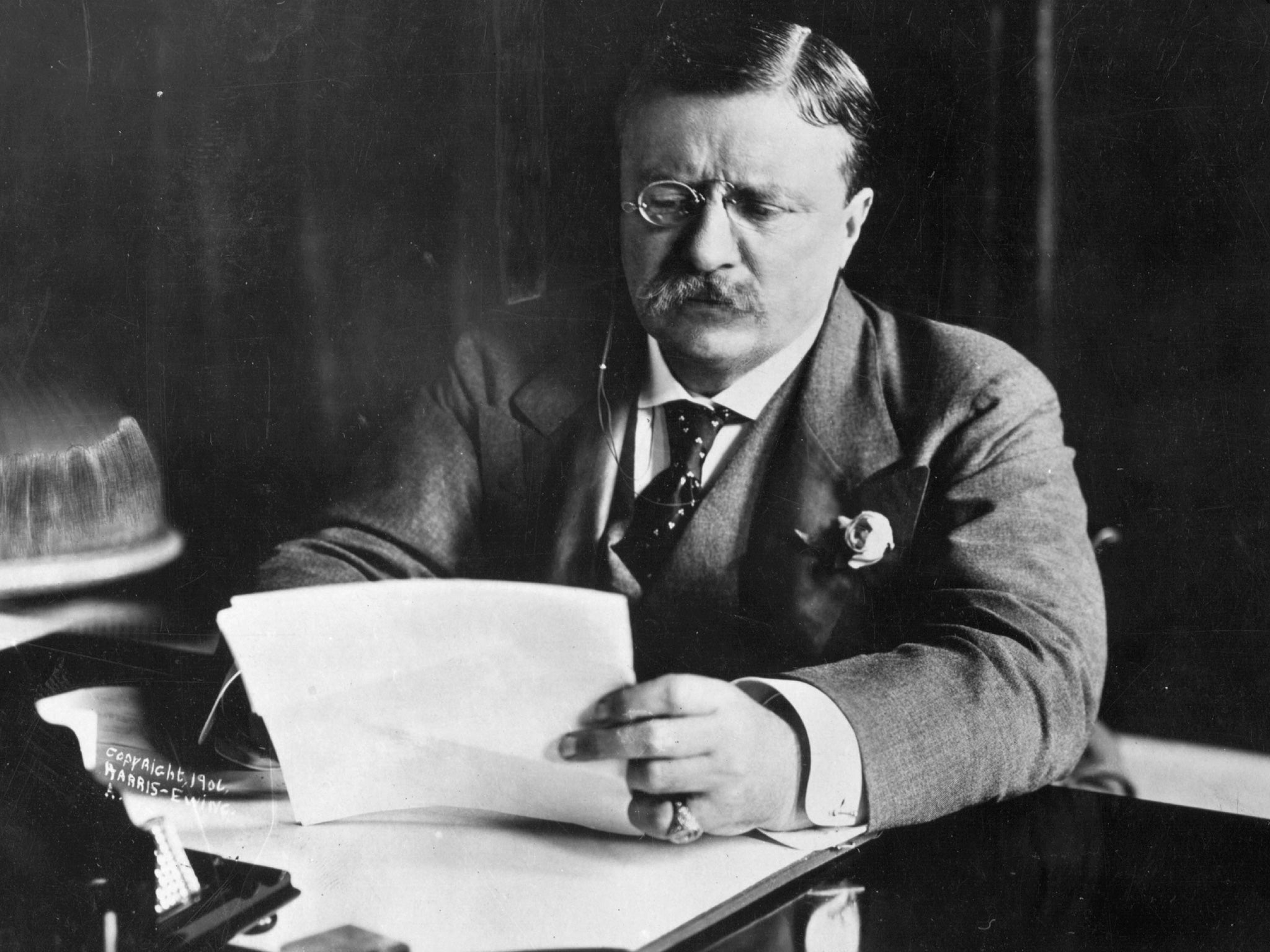

Once upon a time politicians took a more robust approach to market failure. In the early years of the 20th century, President Theodore Roosevelt broke up John Rockefeller’s Standard Oil empire into 34 pieces in the name of getting a better deal for the American public. And after evidence of epic malfeasance emerged in the wake of the 1929 Wall Street Crash, the banking leviathan created by John Pierpont Morgan was cleaved in two by government fiat.

One can imagine how the competition authorities of our own era would have responded to those challenges. JP Morgan’s retail and investment banks would have been “ring-fenced”. Standard Oil would have been required to disclose its internal cost of pumping oil and the price at which it sold the black stuff to customers. Yet it’s hard to find an economist today who argues that it was a mistake for the US authorities to wield the axe all those decades ago.

The CMA argues that creating more providers in banking and energy is pointless if customers remain disengaged. But this is unimaginative. It is reasonable to believe that break-ups would drive cultural change among senior bosses of large banks, focusing their minds on the need to satisfy retail customers. And shattering the vertical integration of the energy companies could also incentivise the decision makers to concentrate on the disgraceful levels of customer service they provide. In both industries the average profit per company would be smaller, motivating each player to try harder to grow market share.

Trying to nudge customers into behaving more like rational creatures is all very well. But sometimes there is a case for fixing the incentives of the providers too. Markets can benefit from a regulatory axe as well as a Whitehall nudge.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments