Whatever you think of the Iraq War, for the Kurds it was a liberation

Talk of 'invasion' and 'occupation' ignores the effect on a long-suffering minority

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When I walked towards the memorial in Halabja in Iraqi Kurdistan a fortnight ago to attend the commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the genocide, I passed by a seemingly endless stream of images. Men. Women. Children. Entire families. All of them victims of Saddam Hussein’s crime regime. The walls inside the monument are engraved with their names - a bridge between the past and the present.

On March 16, 1988, life was forever changed beyond recognition for the people of Kurdistan. In the early hours of Friday evening, a strange smell filled the air over Halabja. It resembled the scent of fresh apples. What actually rained down was a toxic cocktail of mustard gas and nerve agents.

The perfect weapon. The invisible death.

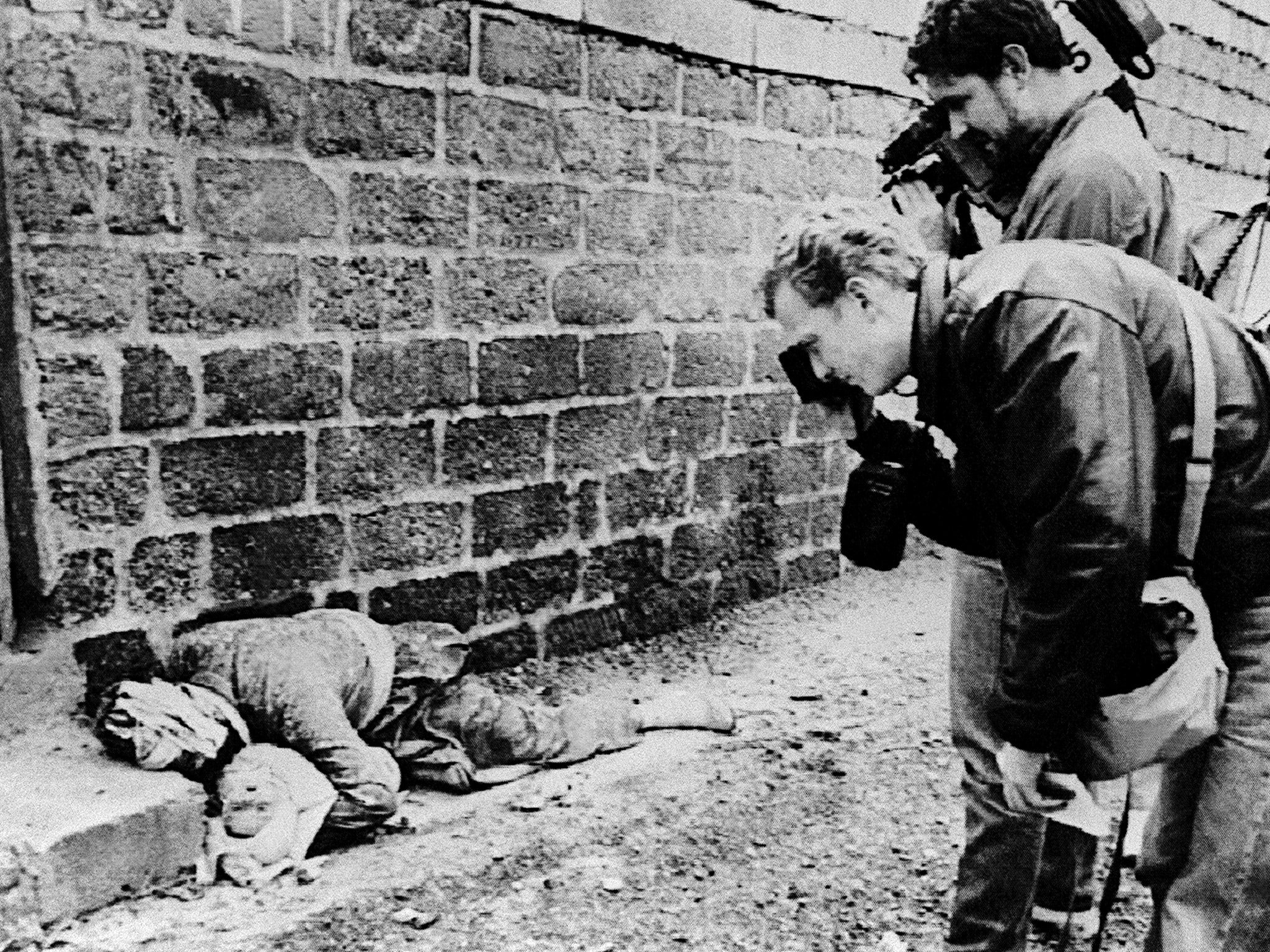

Before they knew the truth, birds were falling from the sky and bodies started piling up in the streets. Some died in their sleep. Others suffocated at work. Still others were found sitting up as if only lost in thought. Some just dropped dead.

Others painfully choked on their own vomit or suffered severe burning and blistering. Children sought the shelter of their mothers' arms but there was no escape. Two days of conventional artillery attacks had destroyed all sanctuaries. The thanatophoric gas was everywhere, mercilessly and indiscriminately filling the lungs of the infants, young and old.

5000 Iraqi Kurds died within seconds. Thousands more were disfigured. The overwhelming majority of them were civilians. They had attacked no one. Their only “crime” was to be Kurdish.

Halabja became a ghost town and it was as if the human race had been eradicated.

The attack was part of the wider genocidal Al-Anfal campaign, initiated by the Iraqi Ba’athists, which claimed over 182,000 lives. Out of 4,655 villages roughly 90% were destroyed and between April 1987 and August 1988, 250 towns and villages were exposed to chemical weapons. It was the first time a government used such weapons against its own civilian population.

Saddam Hussein was a modern-day Hitler. When I visited one of his concentration camps, the Red House in Sulaymaniyah, it starkly reminded me of Auschwitz. Women were gang-raped for hours in what the prison guards called “party rooms”; men faced mutilation and death in the most barbaric fashion in the notorious torture chambers; foetuses and babies were burnt in incinerators.

The Kurds have experienced their own Holocaust. The crusade against them was not simply a by-product of the Iraq-Iran war but a deliberate act of genocide – the crime of all crimes – the aim to annihilate an entire people.

25 years later, the people of Kurdistan are struggling with their bloody past. It will always be a scar on the soul of the Kurdish nation and will forever be embedded in their collective identity. But there is reason for hope. Their hearts have not been consumed by darkness. While they are still grieving and hurting, they have little appetite for vengeance. The Kurds have learnt an essential lesson: hatred only leads to more suffering and death.

Such spirit was reflected in the motto of the anniversary celebrations – “From Denial To Recognition. From Destruction To Construction. From Tears To Hope”. Kurdistan is now the most prosperous and democratic part of Iraq. As British-Kurdish Member of Parliament Nadhim Zahawi - a speaker at the genocide conference in Erbil - pointed out, Kurdistan has become one of the safest places for Christians in the Middle East. Business is booming. New houses are being built on every corner. The peace is fragile, life is not perfect, but when you talk to ordinary people you realise just how far the region has come.

Whatever you may think of the controversial war in 2003, for the Kurds it came as liberation rather than an invasion or occupation. The vast majority hold no animosity towards America or Britain. In fact, they are grateful for the roles we played in the removal of Saddam Hussein.

To say that he possessed no WMDs is not a popular thing to say with people still suffering from the consequences of the very same weapons; and the argument, made by some of the opponents of the war, that the Ba’athist regime someone provided stability and contained Iran is perceived as a hideous excuse and apology for genocide and ethnic-cleansing.

Ten years later, the opinion of Iraqis is virtually absent from the debate in the West. If we ever want to gain a balanced and nuanced view of the complexities of the lead-up to the war, it is time to give the victims of Saddam Hussein’s reign of terror the attention they deserve.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments