From Westboro Baptist Church to Israel-Palestine: What changes people’s views

‘Over time, it became clear to me that the doctrines I had been taught were wrong, that the arguments were circular, and that we were unnecessarily hurting people’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Megan Phelps-Roper has an interesting past. Granddaughter of the notorious Westboro Baptist Church preacher Fred Phelps and former spokesperson for the organization, she is now a political activist who works to promote understanding between extremists. The Westboro Baptist Church are best known for standing on public sidewalks holding protest signs saying that “God Hates F**s” and celebrating the tragedies of others as righteous judgments of an angry God. Phelps-Roper grew up on their compound in Kansas and was pictured as a child wearing offensive T-shirts and standing proudly alongside placards that also included the statements “God Hates Jews” and “America is Doomed”.

When Phelps-Roper turned to Twitter to preach on the platform, people listened, and challenged her way of thinking. It was the beginning of an unraveling that she details in her book “Unfollow: A Journey From Hatred to Hope”.

“The interesting thing is that I didn’t view our worldview or our actions [in the Westboro Baptist Church] as hateful; I believed it was the opposite, and didn’t feel motivated by hate,” she told me. “Over time, it became clear to me that the doctrines I had been taught were wrong, that the arguments were circular, and that we were unnecessarily hurting people.”

It also became clear to Phelps-Roper that the problems within her church were common in American society: “I used to think most people weren’t like Westboro, but it’s become more and more apparent to me that these problems — tribalism, confirmation bias, scapegoating, the flattening of complex situations into black-and-white moral pronouncements — are not Westboro problems.”

Because that kind of thinking has become the norm, she continued, staying silent is now its own form of violence: “Looking away or staying silent — particularly when so many people are doing so — gives the illusion that we approve of that violence, and that the people engaging in crime and slandering innocent people are free to continue their activities without obstacle.”

Phelps-Roper changed, but most in her position don’t. “Hate is taught as a belief system to children and hating becomes a way to be part of the group identity of a family. Often those who hate don’t really understand why they are hating,” explained Erica Komisar, the psychoanalyst and parent guidance expert.

The issue of religious hate and its effects is close to my heart. In 1989, three of my family members were hurt in a terrorist attack in Israel. My uncle, aunt and cousin were on a bus when Abed al-Hadi Ghanem, a member of a group named Palestinian Islamic Jihad, attacked the bus driver and sent the bus careening 400 feet down the mountain, one of the highest points on the drive from Tel-Aviv to Jerusalem. He meticulously planned the attack on his own, riding bus number 405, which left from Tel-Aviv to Jerusalem, several times as he wanted to determine the most lethal place to act.

Sixteen people died in the attack and many were wounded. My family survived because they were thrown out the windows of the bus as it tumbled down the mountain. Young Jewish religious students at a nearby school ran to rescue people and dragged them to safety.

My aunt, Pella Fingersh, told me, “My son survived because at the last second, he was thrown from the bus window before it burst into flames. As opposed to the perceived notion of some who are ignorant to the facts, the terrorist was treated in a private room, next door to my son’s at Hadassah hospital in Jerusalem. He received the same medical attention by the same doctors and nurses who treated his victims. He survived, while some of his victims did not. Forty-two people boarded that bus in Tel- Aviv and by the time it was over 16 people were dead.”

My family members were all hospitalized; my 25-year-old cousin underwent emergency surgeries and has had to deal with lifelong health issues.

According to the Jerusalem Post, Ghanem believed he was acting on behalf of a friend of his who had been injured during the First Intifada.

Antisemitism has marked my family’s movements round the globe. In Germany, my paternal grandfather was a World War I war hero who received the Ernst Ludwig Award for Bravery and the Iron Cross for Bravery in 1917. Yet he was forced to flee to Rhodesia in 1938 because of Hitler and the rise of Nazism.

Years later, in 1995, I moved to New York City with no job, no friends and no money, but with a goal to work in broadcast news. I stayed with my sister’s best friend from college, Chris and his roommate, Hassan Wahla, who was from Pakistan.

Hassan and I had divergent views — especially on Israel-Palestine — but developed a deep friendship based on mutual respect. He showed me his passport, which did not allow him to go to Israel, as well as an ornate box presented to his father, a general in the Pakistani Army, from Yasser Arafat. I recounted happy childhood memories in Israel and time spent with my grandfather who was born in Palestine and fought in the Arab-Israeli War of 1948.

Hassan and I listened, argued and disagreed about nearly everything political, but kept talking.

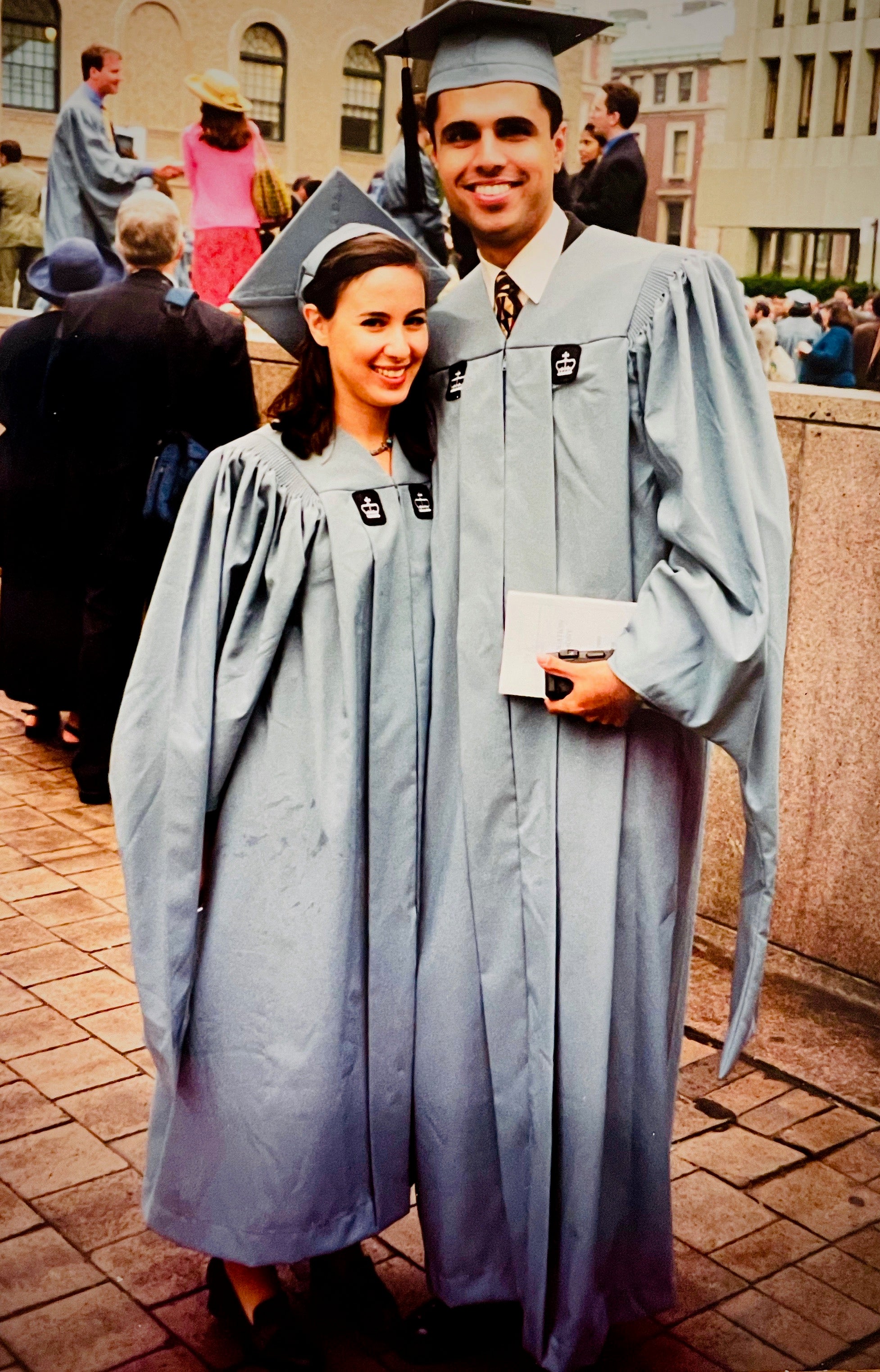

Long after I’d moved out, I stopped by to see Hassan. He handed me a brochure about Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and said I should apply. Two days later, I came by to thank him and tell him I was going to get an application. He smiled and said, “Here — they accidentally sent me two applications. Have the other one.”

We both were accepted, and our friendship has been enduring. During the Trump administration, when so many Muslims felt justifiably threatened by the former president’s policies and his often hateful speech, I reached out again to Hassan, asking, “How can I help? I’m here if you need anything.” I knew how he felt, because antisemitism was also on the rise. A recent survey by the Pew Center indicated more than nine out of ten American Jews say there is at least “some antisemitism in the US” and that 75 percent believe there is more antisemitism in the US than there was five years ago. It also discovered that more than half of the Jewish people surveyed say they personally felt less safe in the US than they did just five years prior.

I’ve often thought that if the son of a Pakistani general and the granddaughter of a Zionist fighter can be firm friends — and have one another’s back in the tough times — then anything is possible. Megan Phelps-Roper’s turn toward compassion and tolerance from extremism and hate is another example of how even a small amount of exposure to opposite views can be transformative. Yet a Reuters poll (Dunsmuir, 2013) found that white Americans are far less likely to have friends of another race than non-white Americans, with about 40 percent of white Americans having only white friends, while about 25 percent of non-white Americans also only socialize with people of their own race. Another study using “egocentric network analysis” designed to assess the scope of diversity of Americans’ social networks found that those networks primarily comprise people from the same racial or ethnic background, especially when it comes to white Americans. Among white Americans, 91 percent of the people in their social networks were white. Among Black Americans, 83 percent percent of people in their social networks were Black. And among Hispanic Americans, 64 percent of the people in their social networks were also Hispanic (Pubic Religion Research Center (PRRC), 2013). It’s clear that to achieve a truly diverse network, it’s necessary to actively put in the effort.

When I asked Hassan recently about his experience of coming to New York and meeting me, he said, “Growing up in Pakistan, it was easy to buy into the narrative against our enemies, India and Israel. However, going to university in the US and then living in New York allowed me to interact and build personal connections and friendships with Indians and Israelis. I realized we have more in common than I thought.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments