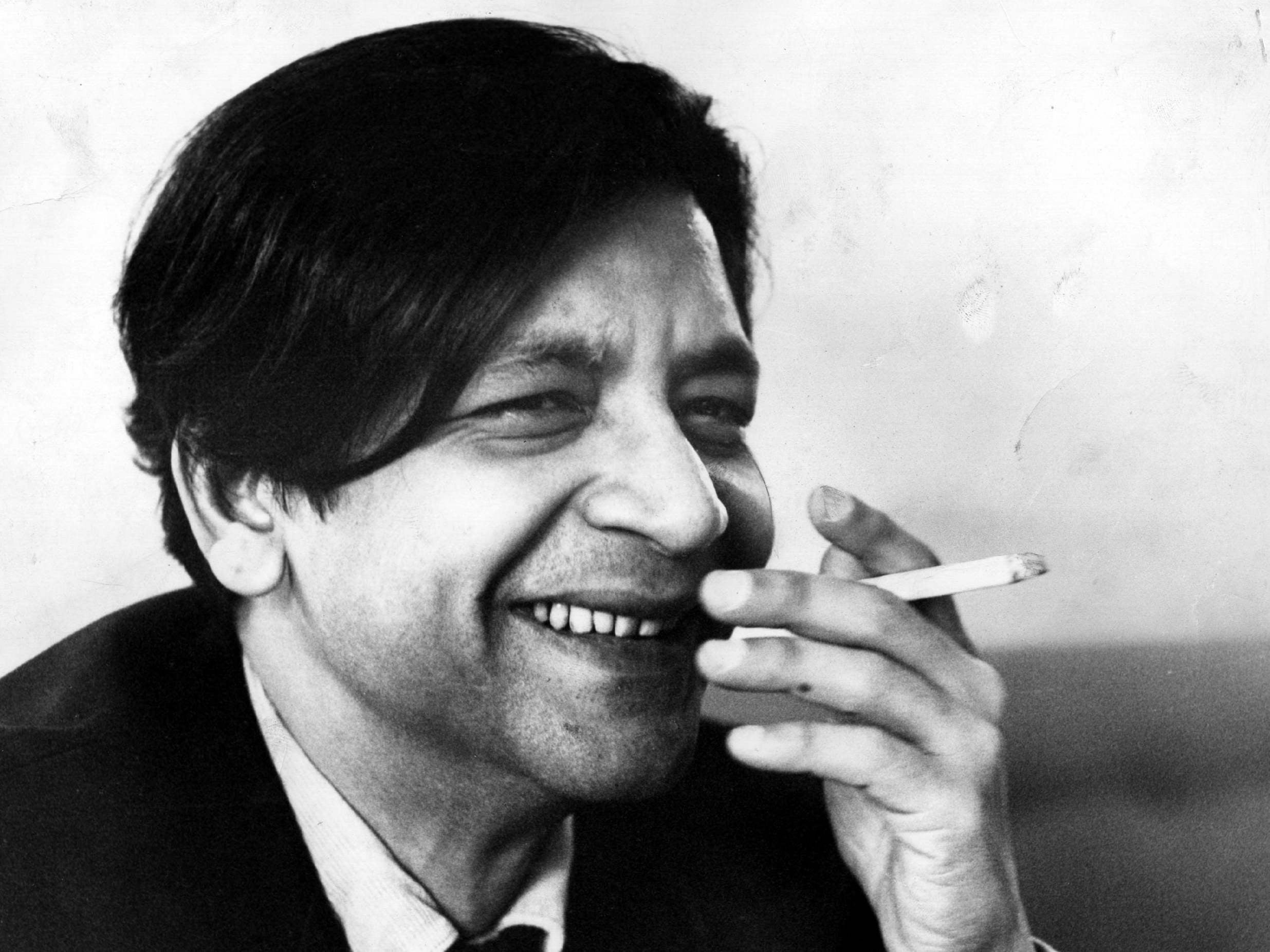

Nobel Laureate V S Naipaul’s personal life may have created controversies but his genius overshadows them

To what extent should the personal life of an artist impact our appreciation of their work? Robert McCrum explains

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the obsequies for the departed, it was once customary to respect the Roman mortuary aphorism “De mortuis nil nisi bonum” (Of the dead, nothing but good should be said). Is it just another symptom of the contemporary disruption that De Mortuis has been replaced by Anything Goes?

The sad and untimely death of Patrick French, the acclaimed biographer of VS Naipaul, has revived like thunder clouds the controversies that once accumulated around The World Is What It Is: The Authorised Biography on first publication.

Art and life must always be in dialogue, but the remorseless way in which some of French’s obituaries have returned to Naipaul’s penchant for prostitutes, the sado-masochism of his adulterous relationship with Margaret Gooding, and the novelist’s self-confessed cruelties towards his first wife Pat, recur as an unappealing reminder of a sanctimonious contemporary squeamishness that tarnishes the memory of Naipaul’s genius.

These re-litigated arguments about what is or is not fair game in a literary life, and how that colours posterity’s judgement of his gifts, cruelly revive all the old animosity Vidia Naipaul suffered during his long career. Not that he would have been surprised, still less cared a jot. Indeed, if we now know rather too much about Naipaul, it’s because, with awesome sang-froid, he authorised French to expose it in the pages of his classic biography.

For most of his 85 years, Naipaul was fully attuned to his own significance. “My story is a kind of cultural history”, he once told me. At the same time, resisting over-simplifications, he liked to quote Proust’s Against Sainte-Beuve: “A book is the product of a different self from the self we manifest in our habits.” Proust’s words were a credo for Naipaul who believed that, in the mystery of a writer’s career, there was “a private life, a public life, and a secret life”.

It’s surely the measure of his greatness and importance that he never flinched from an exploration of that secret, inner life in the broadest sense. This was all of a piece with the precocious ease with which, in his early work, he interrogated his cultural inheritance.

In 1961, A House for Mr Biswas, his brilliant portrait of a Trinidad family coming painfully to terms with the dissolution of British colonialism, anatomised a way of life that had inspired deep and painful conflicts within.

Yet, once secure in the Anglo-American literary world, Naipaul set out to explore the lost India of his childhood and the rejected colonialism of his adolescence, “two spheres of darkness”, first in fiction and then in An Area of Darkness (1964) and India: A Wounded Civilisation (1977). Naipaul’s travels inspired the mature fictions of his middle years, a vision with a darker hue.

During a lifetime of fearless devotion to English prose, he became celebrated for his ruthless, paint-stripping candour; his influential re-making of English prose; and finally an intense, admirable communing with his private demons; the inspiration for his greatest work.

I can recall the thrill of first opening In A Free State (1971). Throughout the Seventies, he forged a style at once grand yet intimate; elevated but austere; public yet secret. Soon, he’d sealed his mastery of the English novel with Guerrillas (1975), and finally with A Bend in The River (1979).

In a teasing penchant for inscrutability, Naipaul would always say that this, his masterpiece “remains mysterious”. At the same time, the novel bravely recapitulates Naipaul’s own inner journey of heart and mind, but in a darker context.

A Bend in The River presents a vision of disorder and decline at a moment of post-imperial upheaval. This made him vulnerable to accusations of reactionary artistic politics. However, with hindsight, Naipaul’s dialogue articulates a haunting inner vision for our times: “We’re all going to hell, and every man knows this in his bones. We’re being killed. Nothing has any meaning … It’s a nightmare – nowhere is safe now.”

When A Bend in The River exposed a Naipaul whom some readers came to disparage, he answered with the frosty hauteur of a Conrad. In 1980, he said to an audience in Trinidad: “I can’t see a Monkey – you can use a capital M, an affectionate word for the generality – reading my work.”

This was shocking no doubt, a saucy prelude to Naipaul’s famous assault on Islam and Muslim fundamentalism in Among the Believers (1981). Before he “authorised” Patrick French’s classic (but controversial) biography, these were the books that provoked apoplexy in the Arab world.

Was it, perhaps, the taste he now acquired for the necessary frisson of self-interrogating his secret life that inspired the allegedly shameful revelations of The World Is What It Is?

We shall never know. Naipaul was always a volatile mix of arrogance and modesty, pride and insecurity, whose brilliant combustion illuminated the world in new, and arresting, ways. In his prime, Naipaul was our greatest living writer, a master of English prose as sharp and lucid as splinters of glass, with a special kind of quotidian radiance.

I remember – and celebrate – him as a delightful enigma, who may also have been a bit of a puzzle to himself. To elucidate this mystery, he would always point to the fearless revelations of his life’s work.

“I am”, he once wrote, “the sum of my books. The self that writes the books is the most secret and deepest.” This Naipaul was tormented by an acerbic self-belief that could at any moment eviscerate what he saw as the lethal trifecta of sentimentality, political correctness and liberal cant.

And yet, in the reflective mood of old age, this Naipaul was far removed from the prickly, awkward figure of yellow press clippings, and Paul Theroux’s bitter memoir Sir Vidia’s Shadow. The scornful misanthrope who stalks through those pages, throwing off asides about “infies” and “Mr Woggy”, now morphed into someone much more mellow.

For Vidia Naipaul, the craft of writing was shrouded in mystery. “I’ve got to believe in the mystery of creativity,” he said. But he never lost his sense of obligation to that quest. “You’ve got to do it,” he told me once. “You can’t just sit and wait for the beautiful idea to form in your mind before writing. You’ve got to go out and meet it.”

Robert McCrum is a former literary editor for the Observer

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments