Research shows class doesn’t explain voting any more – here’s how we should analyse politics instead

New research exclusive to The Independent sheds light on the 10 ‘value clans’ that predict voting behaviour in the post-class era

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

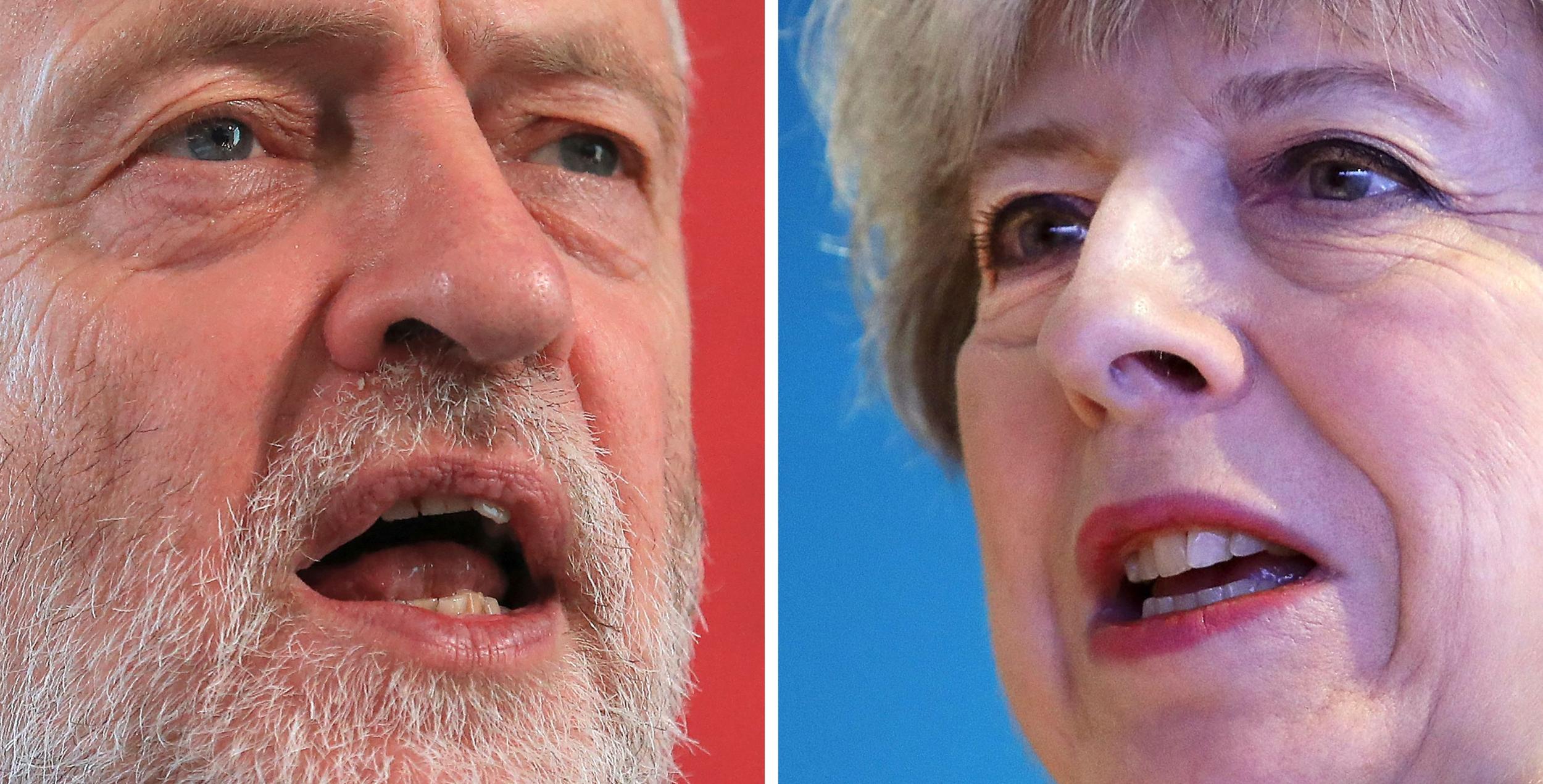

Your support makes all the difference.One of the most remarkable features of the 2017 election was that Labour ceased to be the predominantly working-class party. Despite being led by its supposedly most left-wing leader ever, one who rejected the allegedly middle-class or even pro-rich politics of Tony Blair, there was hardly any class difference between Labour and Conservative voters.

That means that many of the old assumptions about how British electoral politics work no longer applied. If class isn’t the main predictor of voting behaviour what is? One answer, which has attracted a lot of attention, is age, in that most people under the age of 42 voted Labour and most people above that age voted Conservative. But there is obviously more to the shifting patterns of voting than that.

Today’s huge research survey by BMG Research, the polling company, reported exclusively by The Independent, provides the fullest picture yet of the 10 “clans” of voters held together by shared values. Instead of class identity, BMG says it is identities based on values that are “highly predictive” of how people vote.

This kind of analysis shows why some non-traditional political subjects became surprisingly important in the election campaign: the ban on fox hunting, the law on the ivory trade and Tim Farron’s views of gay sex. All of these are highly symbolic of the kinds of values that used to be regarded as non-party political, and that would be the subject of free votes in the House of Commons.

This survey sheds new light on what happened in 2017. Despite much talk at the time about the “youthquake” – a sharp increase in turnout among young people who nearly delivered victory to Jeremy Corbyn – the new analysis finds no evidence for it. BMG says its research instead “points to a ‘liberal tremor’, with more liberal-minded voters more likely to turnout in 2017”.

(If you cannot access the interactive questionnaire above it can be completed here.)

The survey provides several other insights into the 2017 election. It shows how the reordering of allegiance on Leave versus Remain lines contributed to a polarising of support among the “value clans” most identified with either side of the Brexit debate.

The strongest Leave-voting clan, the “Bastions of Tradition and the Individual”, the most Thatcherite group, were also the most likely to vote Conservative.

The most Remain-inclined clan, on the other hand, the “Orange Bookers” – named after the pro-globalisation tendency of the Liberal Democrats – gave Tim Farron’s party its solid core. The problem for the Lib Dems is that this clan is small: accounting for just 8 per cent of the electorate.

Labour gained support from another heavily Remain clan, the “Global Green Community”, which makes up 10 per cent of voters. But Corbyn’s ambivalence on Europe allowed Labour to increase its support among clans that were much less enthusiastic about the EU, “Common-Sense Solidarity”, which was one-third Leave, and “Modern Working Life”, which was divided down the middle by the Brexit referendum.

As ever, the names of the various clans are a brave and partially successful attempt to capture the value clusters thrown up by statistical analysis – in this case “latent-class analysis”, which is “a model-based segmentation approach”. This means identifying the opinion poll questions that best divide the population into value-based groups. This research, designed with the help of academics from Manchester and Bristol universities, has produced 27 “golden questions” that allow everyone to be categorised in one of 10 groups.

This means that the research lends itself to an accessible online questionnaire that allows everyone to find out to which group they belong. I was disappointed to end up in “The Measured Middle”. The description says my clan members “are known for not having very strong political views”. But I prefer to imagine that this category is a dumping ground for people whose opinions cannot be easily classified.

However, many of the other clans are recognisable as groups of voters, which is a useful reminder of how many assumptions about political beliefs are mistaken. Several of the groups hold what are conventionally considered to be left-wing views on the economy, yet are sharply divided on the liberal-authoritarian or nationalist-globalist axes. This helps to explain both why Corbyn’s policies are so popular and why Theresa May fitfully advocates policies such as having workers on company boards and help for those on low pay.

Anything that provides us with better ways of understanding voter behaviour than the old left-right labels and the old assumptions of class politics is to be welcomed. But you would expect one of “The Measured Middle” to say that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments