Failure to vaccinate the world’s poorest is not just a health hazard it could threaten global security

A lack of vaccines could destabilise some of the world’s worse-off regions to the point of conflict and mass migration

When the G7 met in June, they pledged 1 billion vaccine doses to Covax for the developing world. But they haven’t yet arrived or even been purchased, let alone packed and sent. While European countries boast vaccination rates above 70 per cent, some of the poorest African countries haven’t reached 2 per cent.

They can’t access enough doses because richer countries are quietly paying premium rates to secure supplies. They also lack the medical, logistical and transport infrastructure required for delivery that we take for granted. That’s why the World Health Organisation’s director-general has urged a moratorium on booster shots until all countries have vaccinated at least 10 per cent of their population.

In the west, we must recognise the resentment and fear that this inequality foments. There’s an obvious moral issue here, as millions in Africa will be admitted to hospital and may die, while in Europe we debate vaccinating teenagers. There’s a health issue as new variants are allowed to develop, spread and eventually travel. But there’s also a security issue for us: a lack of vaccines could destabilise some of the world’s worse-off regions to the point of conflict and mass migration.

In Africa, the additional instability of an already war-torn continent will fuel more migration northwards; elsewhere, conflict zones like Afghanistan, Syria and Yemen have minimal vaccination rates. It is naive to presume that populations in the world’s least stable nations and conflict zones will passively endure Covid continuing to wreak its havoc without any prospect of imminent inoculation. It will become an increasingly powerful push factor for migration, while playing into the hands of those who use such grievances to trigger political unrest. Equally, seeing the vaccine-led economic recovery elsewhere will act as one further pull factor for those stuck in economies unable to achieve the same.

So far, vaccinating the world’s poorest has been framed as a health threat to nations who have achieved mass coverage, like the UK. Undoubtedly this is true. However, we must also see this as a global security threat too, that we in wealthier nations would be foolish to think won’t affect us. We’ve already seen the political and international tensions that the issue of vaccine supplies can cause: just recall the bitter row between the UK and EU back in January that came close to causing a trade embargo.

It is not unreasonable to think that such tensions in less stable parts of the world will play into historical, geopolitical grievances and instigate worse than a war of words. Look at Yemen, where the Houthi rebels are in outright denial about the ravages of Covid in areas they control. Reports of vaccine disinformation and doctors forced to falsify death certificates are just one example of how the failure to get jabs to this conflict zone adds yet one more tragic layer to this long-running, devastating war.

Though we’ve still seen nothing like the immediate international coordination that got us through the financial crisis 10 years ago, there are bright spots. The Covax programme is picking up after a sluggish start. AstraZeneca’s generous decision to provide its easily transportable and storable jab at cost is a remarkably humane gesture that makes earlier, unfounded criticism all the more shameful. The UAE, with its strategic location close to some of the world’s worst-off in Yemen, Somalia and the Horn of Africa, has become the first Middle Eastern country to establish a vaccine production facility, with its Hayat Vax specifically geared towards supplying millions of monthly doses to that region.

Britain has also been quick out the blocks, pledging 100 million doses in all. We are sending 9 million doses now, a further 21 million by the end of the year, and the remainder by next June. Our donation of over $700m (£511.2m), the third-highest and the biggest per capita pledge to Covax shows strong leadership.

However, vaccination rates amongst the world’s poorest remain appallingly low. For us, the end of the pandemic might be in sight. But for populations in the developing world, the nightmare is still only beginning. If wealthy nations don’t now get millions more doses into the arms of the poorest, we are storing up more than just health problems for ourselves. Our collective failure to rapidly vaccinate the developing world could be the next big security threat too.

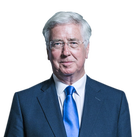

Sir Michael Fallon is the former secretary of state for defence

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments