The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

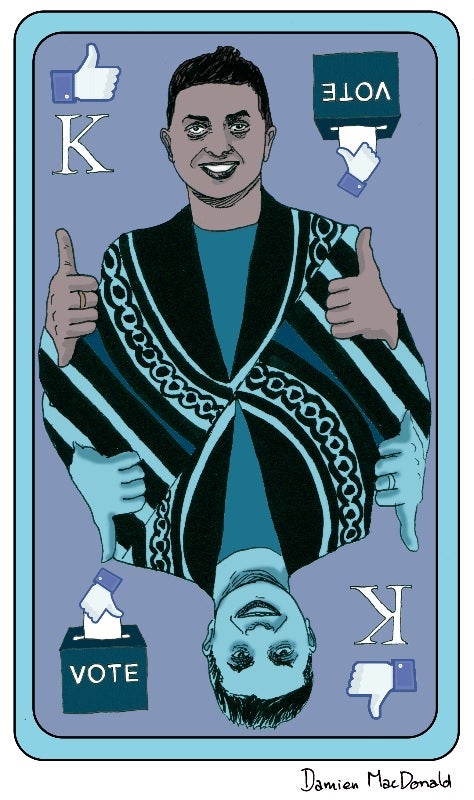

Ukraine’s landslide election result delivers a twist on the new era of populism

Political humour used to be a safe outlet for frustrations that could not be directly voiced and practically resolved. Zelensky has changed that

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Volodymyr Zelensky’s landslide victory in the Ukrainian presidential elections is part of a global tide that has swept populist leaders with little or no political experience to power. Although he has refrained from making electoral promises, the image Zelensky has carefully crafted and presented before voters is that of someone eager to fight corruption and genuinely concerned with finding ways to raise the standards of living for the common folk. He has been so successful that his public persona has practically merged with this fight and this concern.

The case of Zelensky is unique among a group of populist leaders, which now includes Donald Trump in the US, Jaír Bolsonaro in Brazil, and Viktor Orban in Hungary. It would be, perhaps, fair to compare him to Beppe Grillo, a comedian who co-founded the Five Star Movement in Italy.

Zelensky is, like Grillo, a comic actor and, also like Grillo, not a proponent of right-wing populism, though he hardly falls on the left either. If anything, he is a centrist who aims to find a common ground between his country’s restive east and west, or between medium-to-small businesses and the impoverished beneficiaries of woefully underfunded social programmes. But even then the comparison reaches its limit.

When politics is synonymous with “dirty business”, personalities not mired in its wheeling and dealing are perceived as “clean”. Zelensky, of course, did something unusual but unusually effective to strengthen that perception well before he announced he was in the running: for three seasons in a row, he starred as a maverick corruption-fighting president in a popular Ukrainian TV comedy series Servant of the People.

Season one of the series begins in late 2015 with high school history teacher Vasiliy Goloborodko (Zelensky) being secretly filmed by one of his students as he gives an expletive-laden tirade against corruption to a colleague. Predictably, the video goes viral on YouTube, and both web commentators and his own students convince Golobordko to enter the race for the presidency, which he reluctantly does, winning the elections.

Fast-forward to 2019. In an interview, Zelensky and his wife insisted that the thousands of online commentaries to the series, urging him to actually become a presidential contender, were behind his decision to throw his hat into the ring. The final episode of season three, replete with promises of a bright future for the country, aired on 28 March 2019, just three days before the initial round of “real-life” presidential elections. Servant of the People features many recognisable – if exaggerated – personalities from Ukrainian politics, and now the political history of the present has emulated the series.

So today, art does not imitate life; rather, no effort is spared in the task of convincing the viewing public that, given enough will power, life will imitate art. Zelensky’s party was registered two years after the start of the TV series and bears its name. It is this strange feedback loop between would-be reality TV and actual reality that constitutes the cutting edge of “political technology” in the 21st century.

What is the role of humour in the process? It too is rapidly changing. Traditionally, political humour was either a safe outlet for frustrations that could not be directly voiced and practically resolved or a defence mechanism against the excesses of oppression.

With Servant of the People, however, it is no longer a passive defence mechanism but an engine for what I would like to call “apolitical political action”. Instead of temporarily unfastening one from reality, which can be critically glimpsed for what it is thanks to the distance created when one laughs at oneself, Zelensky’s humour aims to shape that very reality without a trace of self-critique.

In the presidency-winning TV series, a corrupt prime minister haggles with the finance minister as to how much of the state budget narod (“the people”) deserves to get – 10, 12 or 15 per cent – after the rest is stolen by various officials and government agencies. This scene, which plays itself out with disdainful irony, is sure to confirm the worst of the viewers’ fears and to make their blood boil with righteous anger. The question is what happens next.

Experiencing strong negative emotions against the system may arouse either reformist or revolutionary desires. Ukrainians are no strangers to mass uprisings, the most recent of which took place just five years ago. Zelensky’s show counsels against this option. It suggests that “the Maidan” (throngs of angry protestors filling Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square) is also sponsored by the oligarchs, who use it for their own purposes, so as to exchange one puppet politician for another.

The remaining option is a reformist one – going to the polls in order to elect not another cadre of the rotten elites, but a simple person who would fix a broken system and heal the country’s wounds. Indeed, that is the premise of the series, prompting its viewers to seek out a messianic defender of the people. Conveniently enough, the defender is going to be fictional prime minister’s nemesis, President Goloborodko, aka Zelensky.

For all intents and purposes, the reformist move is made outside the confines of Servant of the People on an actual voting day. But the outside is also within: indignant viewer-voters have flocked to the candidate of a party christened Servant of the People and cast their votes for a vague amalgam of Goloborodko-Zelensky.

We are at a strange moment in history. The economic world, driven by financial speculation and other varieties of postindustrial capital, has swallowed up “externalities” – or in other words, every area of life that you might have thought lies outside the economic domain. Politics has struggled to keep pace or adapt.

That has helped to create the conditions in which various forms of populism can thrive, and created a curious home for political influence among the normally apolitical strata of the population. As with Trump, and perhaps even Brexit, that thrives on a paradoxically apolitical part of the electorate, unwittingly doing the bidding of “outsider” leadership. Zelensky’s electoral success in Ukraine has written a new, and perhaps more reformist, chapter in this ongoing process.

Michael Marder is Ikerbasque research professor of philosophy at the University of the Basque Country

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments