For decades, immigration laws have stood in the way of the music you love – this is how

This is an issue that has persisted since the 1930s. Depending on what happens with coronavirus, added regulations through Brexit could be devastating for touring acts, writes Nicholas Boston

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Music is the universal language,” wrote the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow almost 200 years ago. A recent Harvard University study proves him right. And, the British sociologist Paul Gilroy has described black music in particular as having a “planetary force”. But, the reality of international borders complicates the matter. In the UK, concern is high and mounting that post-Brexit immigration policy and red tape will turn Britain’s music business from the global industry it currently is into a parochial one for its approximately 191,000 workers across different sectors.

This concern focuses primarily on freedom of movement of British musicians and vocalists to the European Union and vice versa. But it is neither new nor confined to the question of touring.

Immigration control has influenced, in some cases defined, British music for at least a century, industry experts and scholars say. It has done so by blocking entry to performers, whether by individual, musical genre, or nationality; or by interning, surveilling or deporting certain groups of residents deemed at different intervals to be threats or burdens to the nation. This encumbered the creative expression of musicians who were a part of those communities.

“Anti-immigration acts and policies permeate the entire 20th century”, says Florian Scheding, a senior lecturer in music at the University of Bristol who has researched the treatment of immigrant musicians during the Second World War. “The internment of so-called ‘enemy aliens’ and refugees during both world wars springs to mind, as does the treatment of the Windrush generation”.

Indeed, professional performers were among the Windrush passengers. Mona Baptiste, from Trinidad, went on to a successful singing and acting career in England and Germany, while the legendary calypsonian Lord Kitchener (real name Aldwyn Roberts) was preserved for posterity on Pathé News, the premiere documentary news service, performing his song “London is the Place for Me” on the ship’s deck. Meanwhile, voices in parliament were proposing that the Windrush be diverted to East Africa and the job-seeking passengers deposited there to pick peanuts, literally.

Lord Woodbine was a third melody maker on board the Windrush. He is not well known today, but he was the original musical mentor of The Beatles, who in their early years were sometimes called “Woodbine’s Boys”. No wonder that in 2018, when pioneering female rapper Ms Dynamite was bestowed an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire), she explained to miffed fans who felt she should decline it that “honouring my Windrush grandparents and their sacrifices trumps my long-held negative feelings about empire”.

But, immigration control has loomed in the background of British musical life before the Windrush and genres of music historically associated with MOADs (Members of the African Diaspora). Take, for instance, classical music. According to Scheding, between 1933 and 1945, almost 70 composers and some 400 musicians came to Britain as refugees or in exile, fleeing Germany or Nazi-occupied Europe. Many of them got ensnared in Britain’s wartime internment policy which interned German, Austrian and Italian foreigners suspected of harbouring Nazi allegiances. Musicians such as the Viennese pianist Peter Stadlen underwent this detention; he was deported to Australia for two years between 1940 and 1942, until he was granted re-entry to the United Kingdom.

“Musicians had never been the most welcome refugees,” Scheding points out, “and in March 1938, in the wake of the Anschluss and the year of the Degenerate Music exhibition, the Foreign Office decreed ‘minor musicians and commercial artists of all kinds … as prima facie unsuitable’ for entry.”

Turning from classical to jazz and big band music, other regulations related to immigration arose. In 1935, the Musician’s Union, acting to protect British musicians’ job prospects and cultural impact, succeeded in lobbying the Ministry of Labour to deny work permits to so-called dance bands from the US. This was partly in retaliation to the American Federation of Musicians, its counterpart, instituting restrictions on British musicians. The restrictions, which were not absolute, lasted in one form or another for 20 years.

“The UK has never been a consistent ecosystem for jazz”, writes Anton Spice, editor-in-chief of The Vinyl Factory online magazine. “But in fits and starts UK jazz matured, and immigration was central to its growth, providing injections of ideas and inspiration that led to some fantastically esoteric music.”

Scholars Martin Cloonan and Matt Brennan explain how complex the negotiations were in their article “Alien invasions: the British Musicians’ Union and foreign musicians”, which they begin and end with the opinion: “The issue of work permit restrictions for foreign musicians remain a controversial and important part of the history of British music.”

“Sound and citizenship, then, are connected”, writes the ethnomusicologist Tom Western, who studies the intersection of sound, music, and citizenship. Western uses the terms “aural borders” and “national phonography” to describe the post-war efforts in Britain and other European countries to produce a national sound. “Musical representations of nations came into being through international endeavours,” he points out, “while at the same time denying sonic space to peoples and cultures that had crossed borders.”

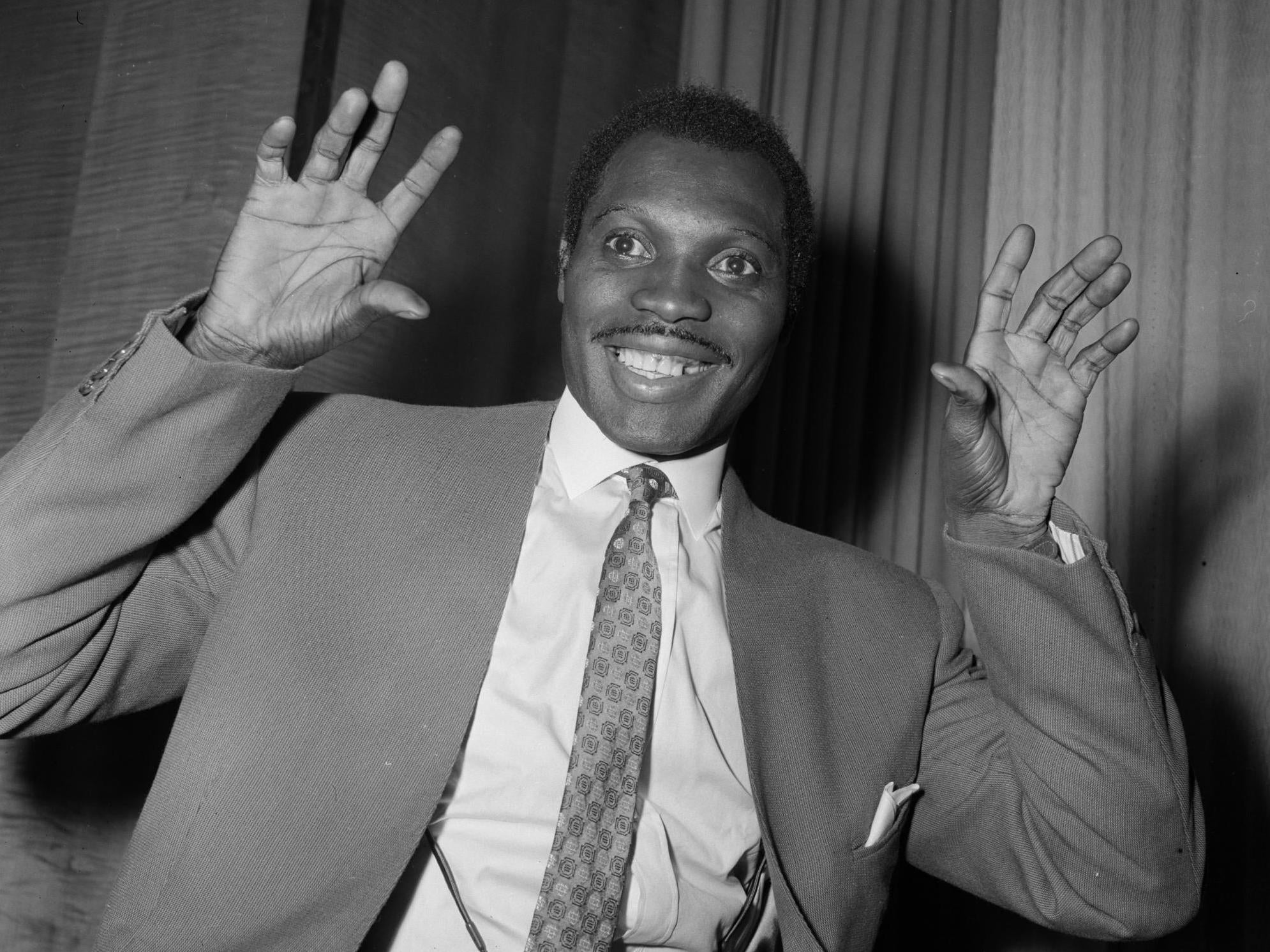

There is a thought-provoking similarity between the album covers for Happy (1975), by the British musician and vocalist Labi Siffre, and Igor (2019), from American hip hop artist Tyler, the Creator. Both show close-ups of the artist’s face looking exaggeratedly glum.

But Siffre and the Creator have more in common than just faux sad expressions. Siffre, born in London to black British parents, produced 11 albums between 1970 and 2006, and his tracks have been covered or sampled by a wide diversity of recording artists, from the ska band Madness to Eminem to Kanye West. Throughout his career, Siffre has been publicly gay. Finally, and not least, he enjoyed global recognition for social justice protest with the anti-apartheid themed song “(Something Inside) So Strong”, later covered by country music icon Kenny Rogers, who passed away last month.

In these and other respects, Siffre is the artist that Tyler, the Creator – whose Igor is ostensibly a tribute to a wrenching relationship he had with a closeted other man and became a lightning rod for protest against UK border regulation – is poised to become. When Tyler, the Creator won the 2020 Brit Award for Best International Male Artist, among the shout-outs he gave at the mic were to “all the British funk from the Eighties that I tried to copy”, “all the UK boys that keep this place fun for me at night”, and “someone who I hold dear to my heart who made it where I couldn’t come to this country five years ago. I know she’s at home pissed off. Thank you, Theresa May.”

On 24 February, Siffre posted a link on his Facebook page to a recently published article questioning the UK government’s plans to tighten immigration control. In the comments below the post, one friend wrote, “The era that you grew up in, I imagine you thought things would get better...? Me too, bewildered by it all.”

And this, really, is the question that remains.

It is yet to be seen what added regulations and costs will be imposed on British acts touring the EU, depending on what happens once the world has a handle on the coronavirus pandemic. “Until we know what trade deals, if any, the UK government negotiates, predicting the actual outcome seems premature,” says John Williamson, a lecturer in music at the University of Glasgow and co-author of the book, Players’ Work Time: A History of the British Musicians’ Union, 1893-2013. “Part of me thinks, or hopes, that the common-sense arguments put forward by lobbying organisations within the music industries like UK Music, of which the Musicians’ Union is part, will be listened to and that, at best, little may change.”

“While it’s too early to be sure about what forms visa regulations will take, it looks likely that the Conservative government will make no exceptions for musicians”, says David Hesmondhalgh, a professor of the media industries and author of Why Music Matters. “And if that happens, it will undoubtedly bring about a drastic reduction in the diversity of music coming to Britain from continental Europe.”

Nicholas Boston is an associate professor of media sociology at Lehman College, the City University of New York

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments