We need urgent government investment rule changes to boost the UK economy

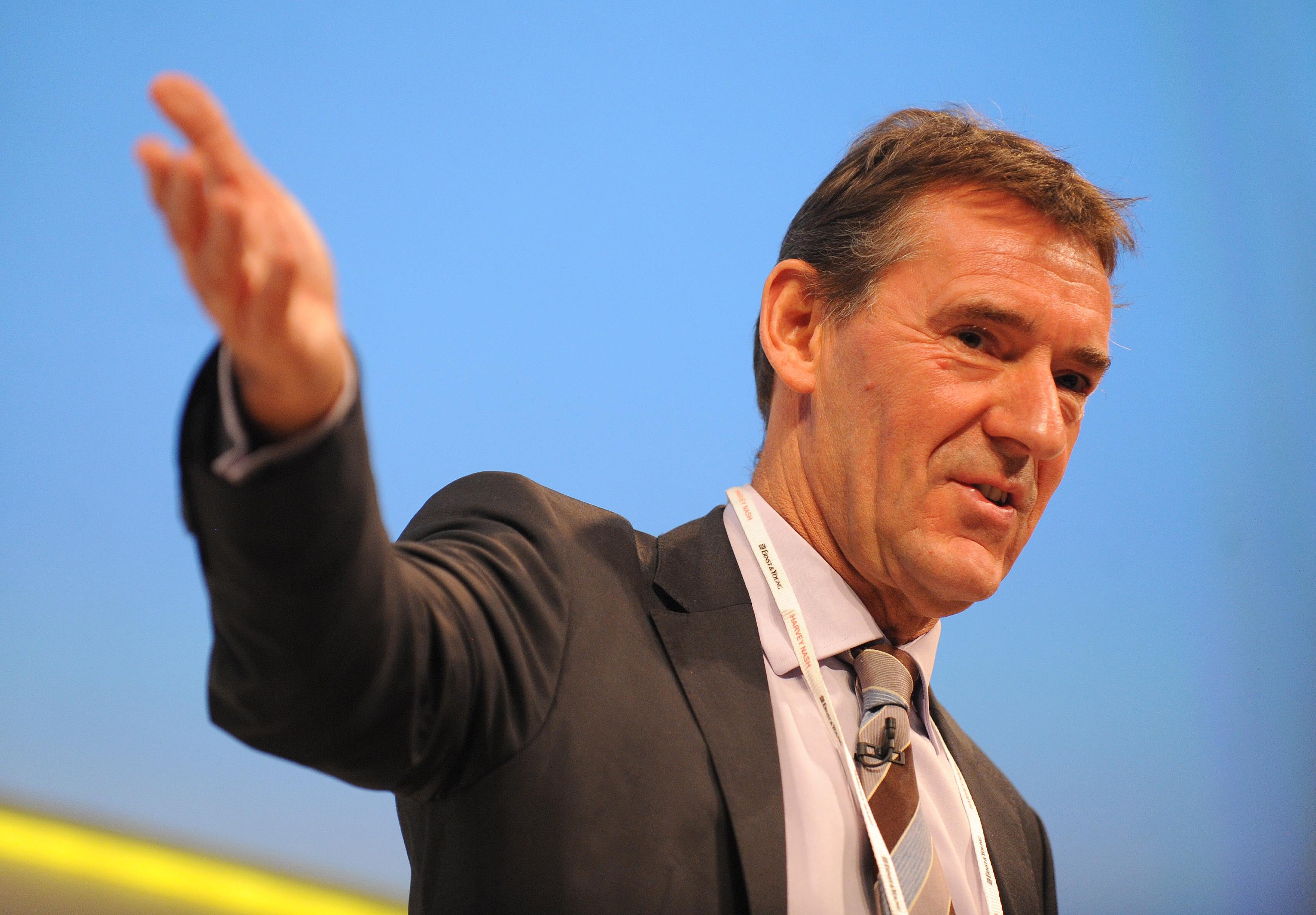

Stop dithering over investment and get our institutions to force the UK to compete and thrive, writes former Tory Treasury minister Jim O'Neill

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Following the latest hike in the Bank of England’s lending rate last week, the chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, suggested that the UK had been stuck in a “low growth trap” for too long, before adding that his autumn financial statement will be the basis of taking us into a more buoyant state.

In a recent interview with ex-prime minister Tony Blair, opposition leader Keir Starmer said that “growth, growth, growth” would be the basis of his overall approach to policy. This follows on from a few months earlier, where he announced in a joint policy paper with his shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves, that they had a mission to have the strongest economic growth rate across the G7, a group of – at least in principle – like-minded advanced economies.

While on the one hand, it is great for an economist like myself to see this apparent commitment to stronger growth, what is more puzzling is they don’t seem to be really thinking especially differently about what really needs to be done to get the country growing in a much stronger manner.

Most economic observers of the UK economic scene share a rather clear basic observation that the UK persistently performs weakly in terms of investment spending compared to its G7 peers (not the most demanding of hurdles) and this is evident in terms of the private sector as well as the government’s own investment spending.

This coincides with a very troubling weak productivity performance that has persisted since the financial crisis of 2008. Given the length of these two coincidental signs of weakness, it seems reasonably obvious that without much stronger investment, spending and productivity growth, the UK will not improve its growth performance.

Both mainstream political parties seem to share an awareness about the need to encourage more genuine long-term investment behaviour from our pension funds and insurance companies in particular, especially into start-up and scaling start-ups from many sectors, in particular those originating from our top universities.

This focus is also something I strongly welcome as the chair of the Northern Gritstone, which serves to bring more patient capital to some of the best commercial research ideas coming from universities in the north. Because of this role, I was asked by Reeves to lead a review for her into what can be done to boost more long-term capital into such vehicles around the country, and she and Starmer adopted many of our recommended ideas to be part of their mission to boost UK growth.

The current government seems to be following a similar line, as evident from Hunt’s recent Mansion House speech and his announcement of a so-called “compact” with some of the largest investment managers to commit to greater such investments, and some generalised suggestion that the British Business Bank (BBB) has been asked to explore ways in which it can facilitate much of this.

In our start-up review, we recommended a clear greater specific role for the British Patient Capital (BPC) arm of the BBB to be central to ensuring more long-term investment is going from the state and private sector into supporting the best ideas coming from our universities as well as other hubs of new value-added business creation.

But as Reeves has stated, in order for the BBB to preside over such a mission, it has to be given enhanced powers, more responsibility, unleash greater ambition and expectations from its leadership and possibly more capital from the Treasury. Indeed, it needs to perform the kind of role that institutions like Temasek in Singapore play in order to have any chance of succeeding.

And it seems one way or another, this may come.

But in my view, this is far from sufficient. As crucial and exciting as our start-up scene in the UK is, there needs to be more for the rest of the overall economy. As is a feature of daily media discussion, infrastructure needs in the UK are vast: whether it be more new forms of cleaner energy; desperately needed Northern Powerhouse Rail – in full across the north; much more London-style transport around many other urban parts of the country; preventive health investments; solutions to logjams like the ridiculous stalemate over Hammersmith Bridge, and so on.

And we need to get the private sector, both domestic and international companies, eager to invest in more facilities for all their businesses, instead of the seemingly endless focus on managing their balance sheets and cash flow retention.

Whenever I speak to a policymaker, they generally agree with these views, but are petrified of doing anything to change it because they feel constrained by the fiscal health – or lack thereof – of the country, and revert to presuming such lofty goals will have to wait for some (miraculous) improvement of the fiscal position.

What is clear to me, and I notice a few influential economic thinkers starting to agree with the core principle, is that we need a government that will break free of this rigid thinking. In recent months the chief executive of the RSA, Andy Haldane, and separately the Resolution Trust, have opined that for public investment spending the government must start to focus on the net public assets of the country – and not the fiscal position – in order that much-needed investments that create large positive multipliers can be unleashed.

In my view the way to do this, as opposed to ignoring them, à la Liz Truss, is to give the OBR much stronger powers in publicly outlining, supported by the Infrastructure Commission, what sorts of investments would have clear, measurable, strong positive multipliers that would create much stronger public assets; and, in the process, probably reducing the fiscal deficit in the future, not boosting it.

And at the same time, drop such petty and arbitrary fiscal rules that magically claim the deficit in five years’ time will be lower. This rarely turns out to be the case, because the introduction of the rule has played a much bigger role in constraining the ability of the government to invest itself, or stimulate investment from the private sector, so that growth ends up being too weak to boost revenues.

The opposition has already declared as part of its mission that it would give the OBR a stronger mandate. I encourage them – or indeed any other aspirational leaders – to go one step further and give such credible independent bodies a central role in allowing the country to invest like any normal country should, to help get the country out of this low growth trap.

Jim O’Neill was commercial secretary to the Treasury under David Cameron, and recently led a review of business and investment for policy for shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments