Keeping calm and carrying on? What’s really behind strong consumer spending in Brexit Britain

There are signs that today’s consumers are not quite the gung-ho big spenders of old

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Britain’s economy has long had all of its eggs in one basket and that basket is not as sturdy as it looks.

I’m talking about the fact that spending by consumers – rather than, say, investment by businesses – accounts for over 60 per cent of our GDP. Judging by the latest official numbers, that engine of growth is still purring away happily. Retail sales unexpectedly rose in June, defying the gloom spreading through other parts of the economy.

No doubt, high employment and strong pay growth have helped to keep tills ringing or, to sound less like it’s 1999, credit cards beeping. But the employment rate, hovering just off a record high, is unlikely to keep rising and the Bank of England expects wage growth to slow later this year.

More worryingly, shoppers have carried on spending for other reasons too, and these are a whole lot less wholesome than a buoyant labour market.

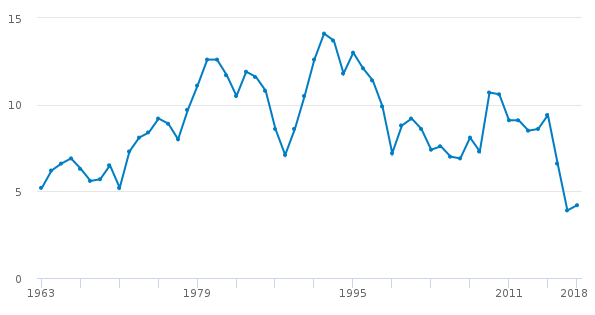

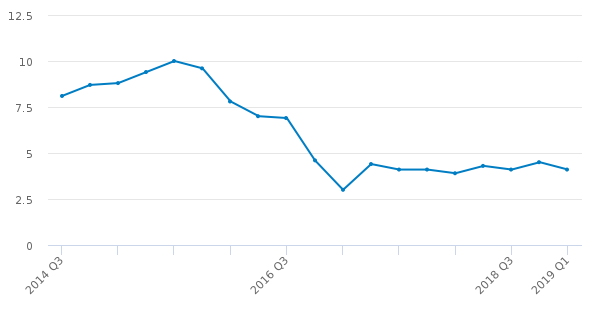

One is the rock-bottom savings ratio, a measure of income being saved. It slumped in the last quarter of 2016 following what Jon Cunliffe at the central bank recently called “a shock to real household income growth” due to the “depreciation of sterling after the referendum and then the inflation that came after”. The savings ratio reached an all-time record low in early 2017 and has since stayed only slightly higher.

There are also signs that today’s consumers are not quite the gung-ho big spenders of old. Government statisticians attributed June’s bounce in retail sales mainly to brisk trade in secondhand goods. Data shows that the quantity of such goods sold has been rising steadily since 2016, jumping 8 per cent last year.

Perhaps aware of shoppers’ increasingly cost-conscious mood, many retailers seem to be holding near-permanent sales. Meanwhile, a price war among supermarkets had driven food prices down and they have still not recovered to their 2014 peak, despite a spike in overall inflation since then.

This is a new world – one where John Lewis, the bellwether of retail, has seen its profits almost halve last year, largely due to discounting, and where upmarket Waitrose is closing stores while no-frills Lidl and Aldi are thriving.

Vacant shops and cut-price clothes strewn across shop floors do not tally with a picture of consumers in rude health.

Neither do some recent survey findings. Data from the Bank of England revealed last week that defaults on credit card debt are rising and at the fastest pace in two years, while a major monthly survey released on Monday showed that UK households continue to worry about job security.

For now, UK consumers are spending, seemingly unfazed by warnings about a hard Brexit. Could this be an example of what psychologists call the optimism bias? This tendency to expect a better outcome for yourself than what actually happens, and what is statistically probable, affects about 80 per cent of people.

The latest GfK survey, closely watched by economists, supports this idea. UK consumers quizzed in June were mildly upbeat about their personal finances over the next 12 months – though less so than they were in May – while at the same time they were extremely downbeat about the economy’s prospects.

The pessimism is bound to spread to spending decisions soon. Either we will start saving more and splurging less as the 31 October deadline nears or we won’t – in which case we will likely cut back on spending once Brexit happens and particularly sharply in a no-deal scenario.

No matter what type of Brexit we get, the increasingly precarious foundations of consumer spending spell trouble for economic growth.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments