Uber and the 'sharing economy' are leaps into the past, not the future

Don't believe the hype: these supposedly post-capitalist solutions are just as likely to shut out the poor and underprivileged

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

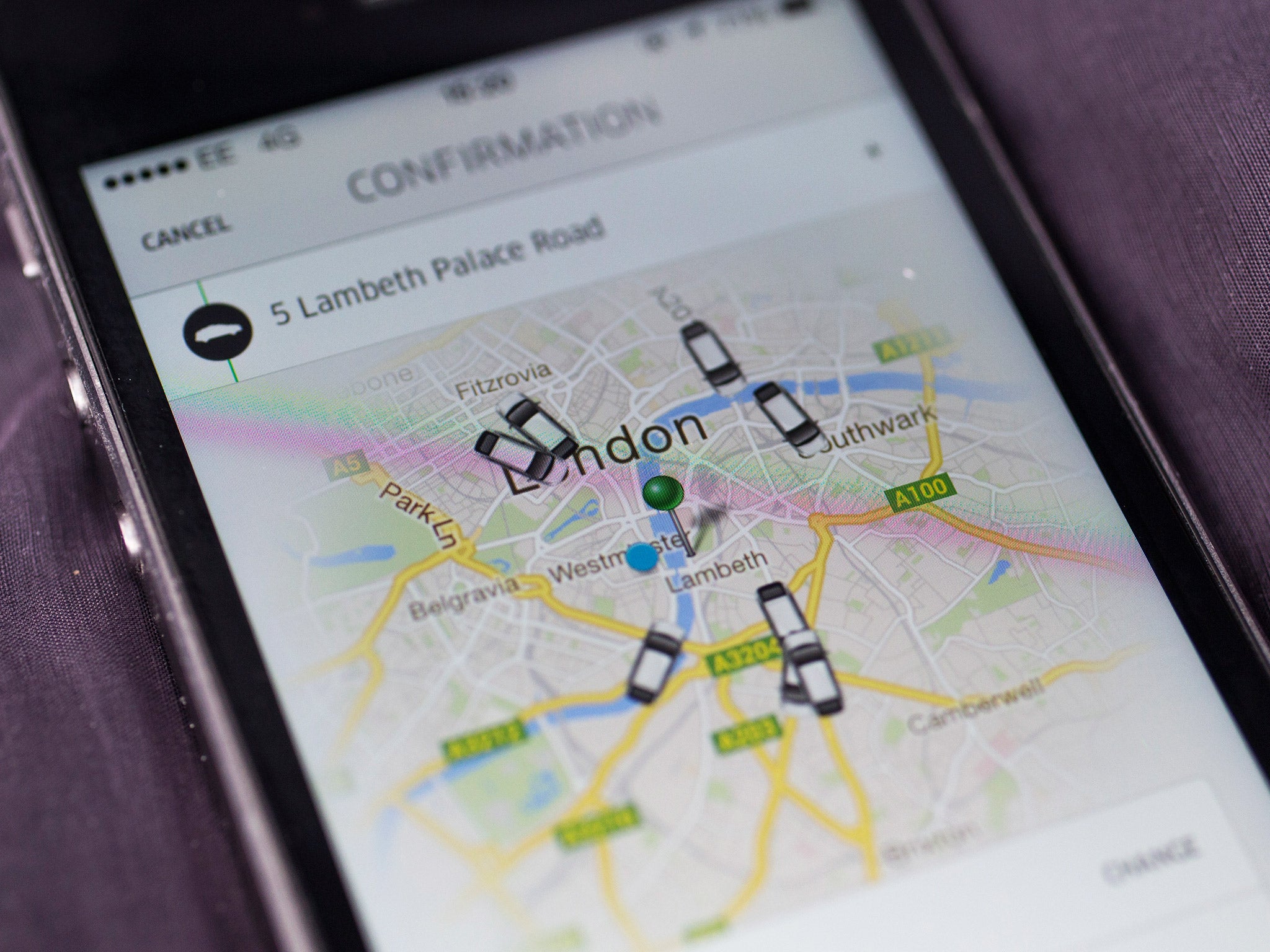

Your support makes all the difference.Let’s say you were commuting in London yesterday. Would you have tried to beat the Tube strike by sharing a black cab and divvying up the costs? Or would you have been super-post-modern, and summoned an Uber car on your smartphone? If the latter, do you think you would have been pleased with the result? Or would you have found out – as many complained during the previous strike – that the caring, sharing economy is the same old capitalist wolf clad in a soft furry sheepskin?

As their rivals from the old economy rushed to point out, Uber drivers tripled their prices during the Tube shutdown, exploiting the rise in demand. I can understand the disappointment of passengers who had expected to pay the usual price for the same journey. But I really cannot understand their surprise.

Uber cars are comparatively cheap because there are more drivers than fares and those fares are unregulated. When something changes to upset the normal ratio – a Tube strike, for instance – of course, drivers will raise the price. The same happened during the terrorist attack in Sydney last December. It is the story of London house prices, school-holiday package deals, variable air fares and hotel rates all over again.

Despite this obvious flaw – call it the market, profiteering, or whatever you will – the so-called “sharing economy” is basking in a new glow of approval, thanks to PostCapitalism: A Guide to Our Future, the latest book by journalist Paul Mason, formerly of BBC Newsnight and now Channel Four. Mason lauds the sharing economy as a harbinger of a whole new way of doing business. He discerns in it the first flags of “post-capitalism”, which he hails as a potentially transformational improvement on the present and proto versions.

There is, however, what he describes as one small condition: that the means of information should be free. This would appear to me to be a rather big condition, given that this is exactly where investors believe the serious money will be made. But I will let that go, because it seems to me that there is far more wrong with the sharing economy than a levy on the means of information.

At first glance, it might appear that the sharing economy has done the nigh-impossible of uniting political left and right on a single economic idea. The left – of which Paul Mason would count himself a proud adherent – likes the communal aspect, the appearance of democratisation, the lack of formal entry requirements that can operate to protect social elites. The right just adores the free-market aspect: the competition that supposedly keeps prices down, and the idea that anyone with get-up-and-go can channel their energy in a small way to improve their lot, without hindrance from red tape or closed shops.

Look more closely, though, and it is only factions on the left and right who have joined forces to lionise the idea. The most vociferous converts to this new-tech form of cooperative – the earliest adopters, you might say – are the chattering classes, as exemplified by Comrade Mason. And this, I would suggest, is no coincidence.

Take another look at the users and the providers. Yes, the sharing principle as applied here may, to an extent, democratise entry. You no longer have to spend months “doing The Knowledge” or pay the set rate for a black cab licence; if you have a respectable car, you can join the Uber force. And if you have a spare room, or a flat in a desirable place (Mason cites a blissful month spent at an Airbnb sublet by Bondi Beach, which he admits might have contributed to his rose-tinted view) you can make some money from it. As you can from a well-placed home driveway, or other fortunate asset. Might the location of a driveway, thanks to the sharing economy, become the same sort of selling point for a house as the proximity of a good state school? Maybe. But who – to ask the old question – really benefits?

To be sure, there are ordinary people with spare rooms, or spare driveways, or some spare time and a car, who will be able to earn something where perhaps they could not before. But there will also be those – mostly elderly and poorer people – who are doubly locked out. They will have neither spare assets nor the technology to access this new economy.

The chief beneficiaries will be the relatively well off, who are simply paying less for the same services they used before. Meanwhile, those in the “obsolete” (regulated) versions of the same sectors take the hit. London cabbies may not carry the greatest conviction when they cast themselves as “victims”, and it may be true that Airbnb may have increased, rather than distorted, the market for short stays. But there are real questions about insurance, standards and tax, which may in the end have to be resolved through the courts. There are questions, too, about quality of life and fairness. What recourse do you have if you are a tenant or home-owner disturbed by anti-social short-stayers? If you are a neighbour woken by driveway customers slamming their doors at 6am? If pollution is increased by the many more cars plying for hire? If wages are further depressed by casualisation?

Health and safety may have become a byword to be ridiculed, but – mostly – there are reasons for regulation. It is the mark of a civilised society that it protects those with less money and clout.

Something similar applies to pricing. There are reasons (quality, hygiene and efficiency, for a start) why most developed countries have department stores and supermarkets, not bazaars. Bargaining takes time; bazaar prices and quality fluctuate wildly. And the have-nots lose out, just as they do in a supposedly caring, sharing economy. Don’t believe the egalitarian, “post-capitalist” hype. Beneath their veneer of modernity, Uber and the like represent the return of the bazaar in the internet age; a leap into the past, not the future.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments