How Turkey's currency turmoil and the uncertainty of the upcoming elections could affect its struggling economy

The country’s challenges extend well beyond the currency markets: the population has been living under state of emergency laws since the coup attempt in July 2016

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Turkish lira has dropped more than 15 per cent this year against the US dollar, and the government is doing all it can to stem the flow. Turkey’s central bank just raised the country’s main interest rate by 1.25 percentage points (to 17.75 per cent) in a bid to stabilise the lira and halt surging inflation. This follows an emergency rate rise on May 23 of three percentage points.

With elections on the horizon, this is a trying time for the Turkish economy – despite the fact that the country’s GDP grew by an impressive 7.4 per cent in 2017. So what’s going on?

There are two sets of troubles facing Turkey at present. The first arises from a change in international financial markets and the second from domestic politics. With domestic economic conditions also deteriorating steadily, the overlapping of these two new sets of difficulties poses a formidable challenge to Turkey’s policymakers, unlike any other since the early 2000s.

The post-2009 global financial crisis period brought happy days for emerging market countries such as Turkey. The dramatic fall in interest rates in the US, UK and eurozone, in response to the crisis, pushed substantial amounts of capital into emerging economies in search of higher yields.

Such low – near zero – interest rates in the developed world remained in place for much longer than expected, allowing the emerging market bonanza to go on for a long time.

That era of easy money is now drawing to a close, with the sharply rising US interest rate, on the back of the strengthening global economy, reversing the flow of capital back into developed countries.

Naturally, the greater an economy’s reliance on external finance, the worse the consequences of money leaving the country. So Turkey, with its substantial current account deficit and need for external finance, has been one of the most vulnerable economies to the tightening in international financial markets.

The second source of Turkey’s current headaches are political and snap elections were announced on April 18, to take place on June 24. This signifies far more than just another set of elections. They represent a watershed moment – for the first time the electorate will be voting for an executive president.

This follows a referendum in 2017 in which the electorate voted, by a small margin, to end the country’s current parliamentary system in favour of a presidential regime. The new regime will be a specially tailored one, with a president armed with extraordinary powers.

Given the scale of the proposed change in the form of government, the uncertainty arising from the upcoming elections is substantial and has wide-ranging implications. With so much at stake at the polls, the government has put in place an enormous election package, further worsening public finances.

It is a well-known principle in financial markets that the greater a borrower’s financing needs, the greater the premium – interest rates – required in securing funds. When combined with heightened political risk, particularly relevant in international borrowing, the outcome is that borrowing becomes even more costly. Hence, Turkey has been offering substantial interest rates to its lenders for some time now.

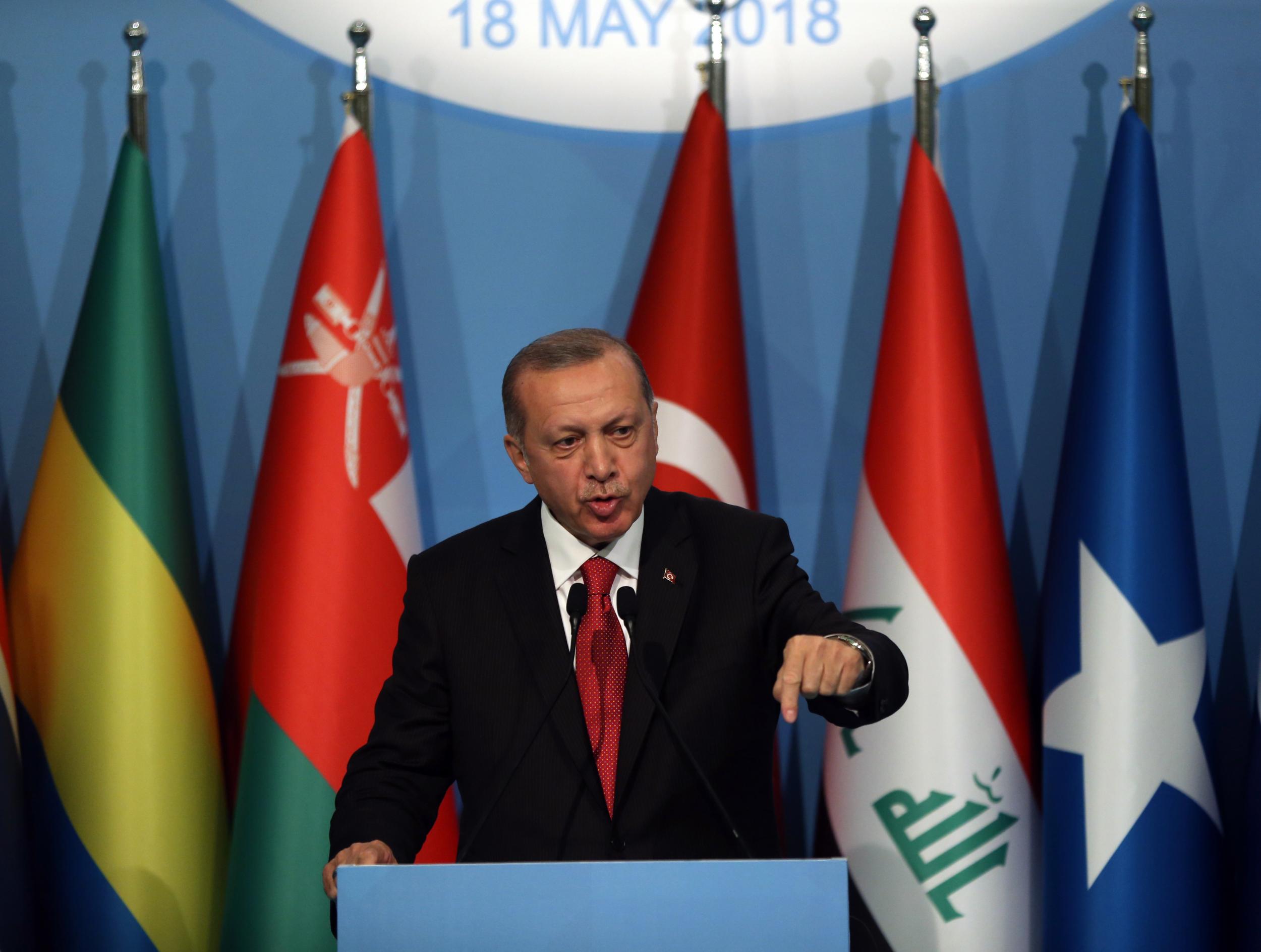

It is therefore not surprising that the Turkish lira plunged to its lowest ever value against the dollar in May, following the president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s comments that “interest rates are the mother and father of all evil”, and that “he would take a more prominent role in monetary policy making” if elected on June 24.

The president also stated his long-held view that “interest rates should be reduced rather than raised to fight inflation” – which is currently running at 12 per cent.

The central bank has acted to control the damage, with two sets of interest rate rises in as many weeks. But Turkey’s challenges extend well beyond the currency markets. The country has been living under state of emergency laws since the coup attempt in July 2016. This allows the president to rule by decree and bypass parliament.

Meanwhile, the Turkish economy has weakened. The solid growth of 2017 followed a massive stimulus, which is clearly unsustainable. There is now widespread evidence that the cheap credit that flew in when the going was good did not flow to productive uses. At the same time, it massively raised the foreign currency debt burden of the private sector, making the country increasingly vulnerable to currency depreciation.

Most importantly, the make up of the new regime – in which the president is expected to be the dominant force – raises serious questions about the separation of power, the rule of law and the independence of the country’s institutions.

The excessive volatility in the currency markets, which followed the president’s threat to interfere with central bank independence, clearly shows that the price of a one-man rule may just be too high for the country to pay.

Gulcin Ozkan is a professor of economics at the University of York. This article first appeared in The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments