Turkey is the biggest threat to Europe today, and the Greeks need our help

As one former foreign minister put it, ‘if the EU’s foreign policy is now vegetarian, German foreign policy is vegan’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Later this week, EU leaders will meet to discuss their recovery plan. They will spend a few minutes on Brexit. EU heads of government look with disbelief at Boris Johnson’s announcement that he will break international law to appease the Brexit obsessives in his party.

But there is nothing Europe can do to cure Britain’s Brexit virus.

Russia is back on the agenda with the confirmation of the attempted murder via poison of Putin’s chief opponent, Alexei Navalny. And across the frontier, the democratic uprising in Belarus will get an airing.

But today, by far the biggest threat to Europe – in terms of a foreign power that is threatening EU territory and almost everything Europe says it seeks to project as its values – comes from Turkey.

Speaking in Athens last week, the former French president, Francois Hollande, laid out his concerns about Turkey.

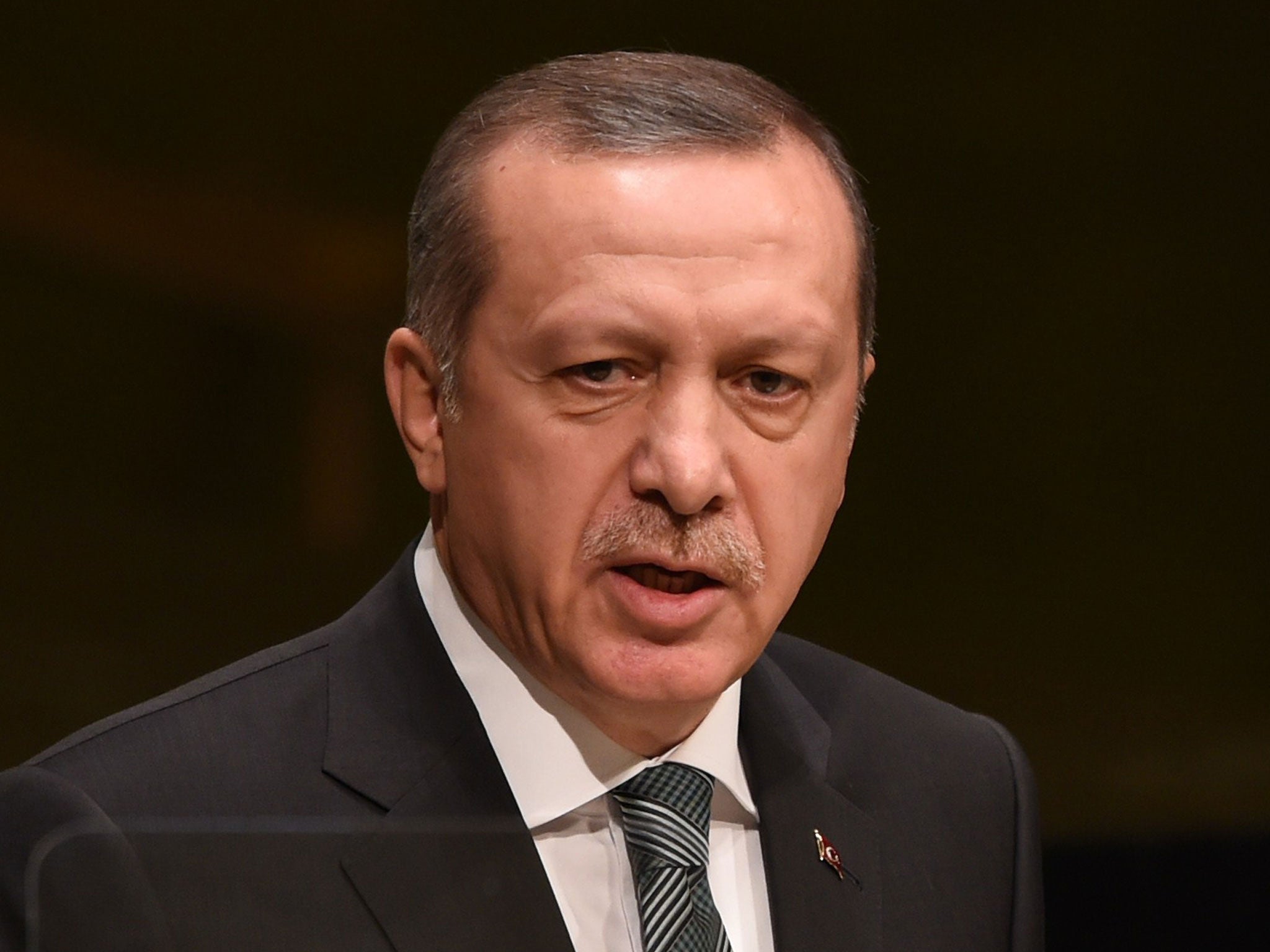

For Hollande, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, now known in diplomatic circles as “The Sultan”, was a threat to Europe. He has led Turkey to economic ruin and now has to beat the nationalist drum, urging the restoration of Ottoman empire glory, in order to divert people’s attention from rising economic problems.

Hollande’s charge sheet includes multiple accusations: Erdogan is seeking to militarise the eastern Mediterranean; he has breached Nato obligations by buying Russian missiles; he has imprisoned hundreds of journalists and political opponents; he is obsessed with Islamism, promoting Islam in Europe and has converted two of the finest Byzantine Christian cathedrals in Istanbul into mosques; he flagrantly interferes in the politics of European countries including France and Germany, holding giant political rallies and insisting that Turkish EU citizens owe loyalty only to Turkey; his adventurism in Syria and his war on the Kurds are dangerous; his alliance with Libya was an act of aggression.

Hollande’s line was music to the ears of Greek ministers attending the conference. Nikos Dendias, the Greek foreign minister, insisted that Greece wanted to work with Erdogan, but only once the threat to the territorial integrity of the island nations of Greece was lifted.

Greece and Cyprus have been trying to get more support from the EU. Britain, with its pro-Turkish prime minister, is no longer a player, to the disappointment of British Hellenophiles.

The main problem for Greece is the refusal of Germany to take a clear line. Speaking after Hollande, the former Social Democratic Party leader, Sigmar Gabriel, who was German foreign minister from 2017 to 2018, took a completely different line. Gabriel insisted that if Turkey was sanctioned for buying Russian S-400 air defence missiles in clear violation of Nato obligations or was made to leave Nato, Turkey would quickly become a nuclear power.

He added that if the EU showed solidarity with Greece and took any measures against Erdogan, Europe would have to build new walls on all its frontiers including internal ones in countries like Hungary, as Erdogan would send a million or more refugees into the EU.

For Gabriel, the main problem was that the United States was not ready to sanction Turkey, and given US sway over Nato, there would be no clear line on Turkish militarisation of the east Mediterranean.

For Gabriel, the answer was “strategic patience” which also should be the policy towards Putin even after the attempt to murder Navalny.

As Gabriel sarcastically put it: “If the EU’s foreign policy is now vegetarian, German foreign policy is vegan”.

German and EU hand-wringing on Turkey was confirmed in an interview with the main Greek paper Kathimerini when the director of the German Council on Foreign Relations, Daniela Schwarzer, also special adviser to the EU foreign policy supreme, Josep Borrell, said proposals to put pressure or sanctions on Erdogan were “complex in a number of ways: whether they should be imposed, to what extent, under what terms – and under what terms they should be lifted”. She added: “We have not yet reached the point of broad and deep sanctions.”

That is precisely the foreign policy veganism from Berlin and Brussels that Sigmar Gabriel mocked. In many EU capitals, the Greece-Turkey dispute is complicated, arcane and lost in every sense in many mists of history.

Recently, Malta’s foreign minister suggested that it was just a matter of talking it all through.

If a power the size of Turkey were threatening to take over Malta’s little island of Gozo, he would be the first to demand solidarity and support from the EU.

On Tuesday, the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, the EU Council president, Charles Michel, and Erdogan have a scheduled Zoom discussion ahead of the council’s meeting later this week. Greece is the main talking point. Will the EU foreign policy vegetarians and vegans let the carnivorous Erdogan help himself to a slice of the Aegean?

Denis MacShane is the UK’s former minister for Europe

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments