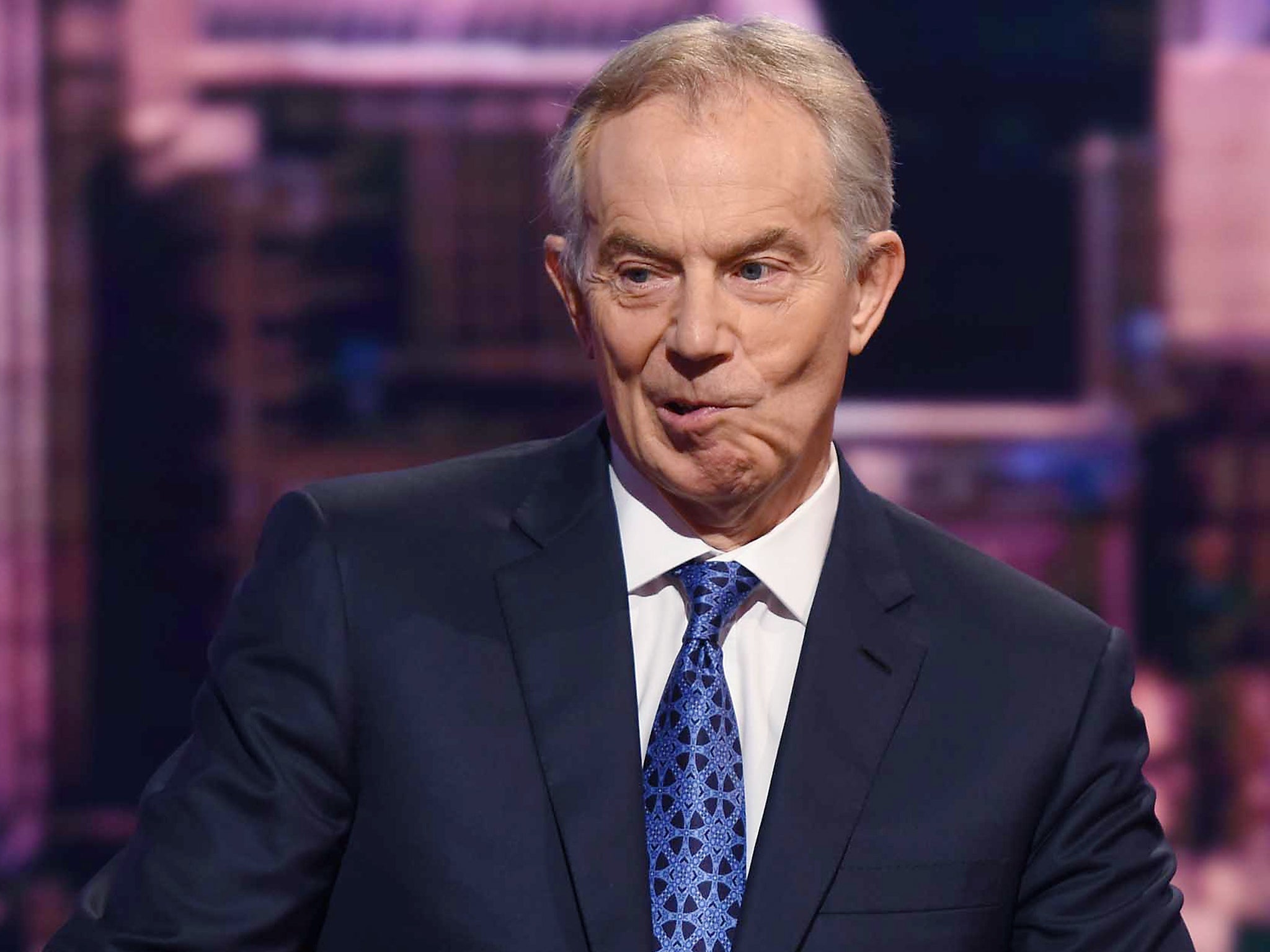

Tony Blair's decisions are what gave us Brexit and Isis – and paved the way for a united Ireland in the future

Allowing free EU movement led to the vote for Brexit. Peace through power-sharing in Northern Ireland may have opened the way for unity. A military mission intended to bring freedom and democracy to Iraq set off a civil war, contributed to the rise of jihadism, and helped discredit elites in the US and here

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One of the downsides of exercising leadership young is that you may live to see, and perhaps rue, some of the unintended consequences. For political leaders that is an especial hazard. Within the space of 48 hours this week, Tony Blair found himself returning to two of his biggest decisions as Prime Minister – allowing unhindered entry to the UK for nationals of the 2004 EU accession states and talking to the IRA – and defending the results.

His first outing was on the BBC’s Andrew Marr Show, in an appearance linked to the launch of his new Institute for Global Change, where he admitted that he had not anticipated the number of people who would come to the UK, especially from East and Central Europe. He was back on the airwaves a couple of days later to talk about Martin McGuinness, noting, with characteristic eloquence, that what had made him such a “formidable foe” had also made him a “formidable peacemaker”.

What the former Prime Minister did not do in either case was to speculate about the longer-term fallout, nor was he asked to. Yet almost 20 years on from the sweeping victory that propelled him to No 10, some of the chickens are coming home to roost, with the prospect of some very much unintended consequences.

Take free movement. Tony Blair started out as a Europhile prime minister, probably the most so since Edward Heath. There was even talk of the UK joining the single currency. Yet because he preferred “enlarging” to “deepening” – as indeed Margaret Thatcher had done – and then underestimated the number of new arrivals so hugely, it can be argued that Blair sowed the seeds for the UK’s departure.

Whatever defence is made of what happened – that the number of new arrivals settled in remarkably well, that they make a net contribution to the economy, that they (mostly) did not depress wages, that we will miss them if and when many of them are gone – the fact is that these arguments were neither universally accepted nor always valid. When the refugee crisis showed the EU unable to secure its borders, even though the UK was largely unaffected, the damage was compounded. On the issues of sovereignty and migration, Brexit won.

Blair’s decision on free movement – taken, as it seems, out of a mixture of idealism, poor information, and a belief that European migration would strengthen the UK economy – may have a further consequence. During the referendum campaign, a Leave vote was widely seen as a possible catalyst for the break-up of the EU. Where the UK led, it was argued, others would feel emboldened to follow.

So far, at least, however, the effect seems to have been the opposite. In what could be the bitterest twist for Tony Blair and the UK’s Europhiles, Brexit seems to be pushing the EU closer together, leaving the UK even more peripheral than it would otherwise have been. In other words, the EU becomes stronger without the UK.

A similarly perverse chain of effects can be foreseen in Ireland. The immediate result of Blair’s decision to authorise talks with the IRA was the hard-won Good Friday agreement of 1998, the entry of Sinn Fein’s Martin McGuinness into the power-sharing government, and an end, more or less, to “The Troubles”. This considerable achievement brought peace, if not actual reconciliation.

The longer term consequence, however, could well be the united Ireland that the Good Friday agreement was partly designed to forestall. If recent elections in Northern Ireland show a trend, it is that sectarianism is declining and that, perhaps thanks to power-sharing, republicanism has been to an extent detoxified.

It is now possible to see a combination of factors – from demographic and cultural change among the younger generation in Northern Ireland, via the flourishing of the Irish Republic in the EU, to fears of what could happen if Brexit requires a hard border with the Republic – that would militate in favour of a united Ireland.

The EU is at least part of the backdrop to the change, because it effectively blurred the border between North and South and fostered cooperation that would otherwise have been impossible. As in Scotland, a majority in Northern Ireland voted for Remain, and the practical problems associated with Brexit are in fact far greater for Northern Ireland than for Scotland. It is no wonder calls are being heard for a referendum on unity. It may not happen soon, but it is the obvious solution, and it would be a consequence – indirect and unintended for sure – of Blair’s efforts to bring peace to Northern Ireland.

No consideration of Tony Blair’s decision-making and its consequences would be complete without a mention of Iraq. His part in the US-led invasion has done perhaps more than anything to blight his legacy at home, undermining his advocacy, for instance, on Europe. It also played a big role in eroding public trust, not just in government, but in the security services, distrust which continues to this day.

With hindsight, the invasion of Iraq can also be seen as the root of much of the turmoil afflicting the Middle East now. Even if it had nothing to do with the so-called Arab Spring, it helped drive Iraq’s Sunnis into the embrace of Isis; the chaos it triggered in Iraq served to strengthen Iran, and the autonomy enjoyed by Iraqi Kurds reinforces Kurdish calls for their own state. At least some of the multiple shifts in the region, now converging in and around Syria, can be traced to the forcible removal of Saddam Hussein.

In his celebrated Labour conference speech after 9/11, Tony Blair spoke of the “kaleidoscope” being shaken; before the pieces settle again, he said, “let us reorder this world around us”. He did indeed start some reordering, but it has not always come out how he may have hoped.

Efforts to reconcile the UK and the EU led via free movement to the vote for Brexit. Peace through power-sharing in Northern Ireland, designed to stave off territorial change, may have opened the way for unity. A military mission intended to bring freedom and democracy to Iraq set off a civil war, contributed to the rise of jihadism, shifted the regional balance of power, gave Western intervention a bad name, and helped discredit elites in the US and here.

Some of this may have been necessary; not all of it is bad. But none of it can be what Tony Blair had in mind all those years ago, when he talked of changing the world for the better and took the decisions he did.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments