This week we find out what kind of Chancellor Philip Hammond really is

Abandoning the target of balancing the Government’s books in 2020 is one thing – losing control of public borrowing altogether is quite another

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Philip Hammond was “straight as an arrow, inventive and could make things work quite quickly”, according to his former business partner, Terry Gregson. I think “straight as an arrow” is a better way of putting it than “dull”, which is the usual description attached to the Chancellor, who will present the Autumn Statement on Wednesday.

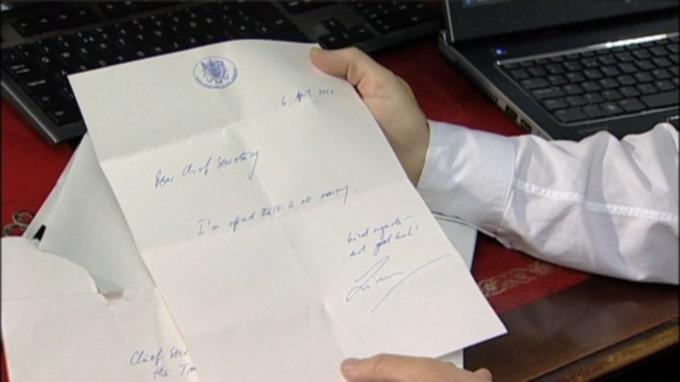

As evidence, I offer the true story of Liam Byrne’s letter. Byrne was Chief Secretary to the Treasury, number two to Alistair Darling, in 2010. Hammond was shadow Chief Secretary, and got on reasonably well with his opposite number. In case Labour lost the election, Byrne left a note for Hammond in his Treasury office: “Dear Chief Secretary, I’m afraid there is no money. Kind regards – and good luck!”

After the election, however, David Cameron and Nick Clegg formed the coalition, and it was David Laws, the Liberal Democrat, who became Chief Secretary. Hammond became Transport Secretary. Laws gleefully made Byrne’s dry humour public, and Byrne’s career was history. A photocopy of the letter became a prop of Cameron’s standard stump speech in the 2015 election.

Recently, I asked Hammond if he would have made the letter public. “No,” he said. “Maybe I am naive but it wouldn’t have occurred to me.”

Hammond is not the kind of chancellor who would have insisted on tax relief for films, as George Osborne did, against advice from officials. Osborne is alleged to have wanted it just so that he could put a joke in his Budget speech, against Ed Miliband and Ed Balls, saying he wanted “to keep Wallace and Gromit exactly where they are”.

Indeed, Hammond’s straightness has led to tensions with Theresa May, who would like him to spend all the money that, as Byrne said, he doesn’t have on her political priorities. She is going to make a speech on Monday about her industrial strategy – an ominous phrase that is always followed by the disclaimer: “We are not talking about the government picking winners or propping up failing companies.” That is what Peter Mandelson said when he made speeches about an industrial strategy after his return to Gordon Brown’s government in 2008. When you have to start by insisting on what your plan is not, you can be pretty sure that is precisely what it is. You would not have thought that May started her career at the Bank of England.

What will also be important in the Autumn Statement is her focus on people who are “just about managing” – a phrase that Daniel Finkelstein of The Times says reminds him of David Moyes. She means those ordinary working-class families she mentioned on arriving in Downing Street who “can just about manage”.

The irony is that there is a big overlap between these people, and those who will lose out from the cuts in tax credits planned by George Osborne for the remaining three and a half years of this Parliament. Osborne cancelled the first wave of these cuts when the House of Lords voted them down, and Hammond could cancel the rest. That would be expensive, but it is possible because May has abandoned the target of balancing the Government’s books by 2020.

But that simply means that the “just about managing” won’t lose out: it doesn’t mean that they would benefit.

Meanwhile, just about everything that could put pressure on the public finances looks as if it may be about to do so. Inflation is likely to rise, putting further strain on low-income households. More and more NHS warning lights are flashing, and the associated problems in social care for the elderly are becoming acute. When Brexit actually happens in 2019 the effect will be very different from the benign impact so far on confidence of the referendum vote. Then there is the possibility of another eurozone crunch or a global recession.

Abandoning the target of a surplus in 2020 is one thing. Losing control of public borrowing altogether is quite another. It may even be sensible for the Government to go on borrowing, especially when interest rates are as low as they are, but it cannot do so for ever.

As usual, Hammond’s statement on Wednesday will be hyped up by the media, but it won’t amount to much. So far, the pre-Autumn-Statement spin from the Treasury – the sort of thing we don’t have any more because Theresa May has returned to traditional cabinet government – has been that he will spend a bit on some roads.

It has been reported that Hammond would like to cut down the hoopla around the Autumn Statement, which under Gordon Brown became in effect a second Budget. No doubt he would, and I am glad that is his instinct, but he will get nowhere with it. The Treasury is part of the showbiz of politics now. The best we can hope for is a Chancellor who is “straight as an arrow”. If he is also “inventive” and able to “make things work quite quickly”, so much the better.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments