This is one proposed pension raid on the rich that isn’t justified

Politicians are a cynical breed. They have most likely targeted pension contributions relief in recent years because relatively few grasp how the system actually works

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The art of raising taxes, as we all know, is plucking the goose with the minimum amount of hissing. In recent years, the Chancellor has found that curtailing private pension tax relief for higher earners has been a way of raising revenues without too much of a feathery flap. George Osborne has raised around £5bn a year in revenues since 2010 by progressively squeezing down the annual tax-free pension contribution limit and the maximum tax-free lifetime pot. His predecessors at the Treasury raised money in similar sorts of ways.

But now the goose is getting seriously squawky as the Chancellor reportedly considers an almighty pluck in next month’s Budget – imposing a flat rate of pension contribution relief to replace the current system where, for example, 40 per cent taxpayers get 40 per cent relief on their contributions and 20 per cent taxpayers get 20 per cent.

Some right-wing newspapers, encouraged by lobby groups for savers, are attacking the proposal in advance, howling bitterly over its unfairness. This particular coalition can normally be relied on to champion the wrong economic causes. But in this instance the lobby is right.

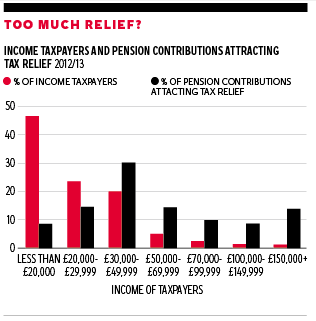

Some who have pushed in the past for a flat rate of pension tax relief (including the previous Coalition pensions minister Steve Webb and also the present incumbent Ros Altmann) have done so on the grounds of “fairness”. They point to HM Revenue and Customs calculations showing that the cost of the relief is considerable – currently around £34bn a year – and that the bulk of it flows to high earners. And from this they draw the conclusion that restricting relief for high earners is a fair and simple way of raising more money from the rich.

But this ignores the fact that relief on pension contributions is merely tax deferred – not, as many seem to think, tax avoided for all time. Everyone pays income tax on any income they draw from their accumulated savings pot in retirement. So if someone on the 40 per cent rate gets 40 per cent relief on their monthly pension contributions, this isn’t some sort of free gift from HMRC. When they draw down this money in retirement, they will pay tax on it.

Confronted with this reality, some still object that many individuals paying the higher rate may only be basic-rate taxpayers by the time they come to retire. But the answer to that is: so what? The objective of the system is to tax incomes when people realise them. If people’s incomes fluctuate over their lifetime, their marginal tax rate should fluctuate too. And so should their rate of pension contribution relief.

If they pay higher rates of tax at various stages in their life, it is surely fair that they also benefit from higher rates of tax relief on savings.

None of this is to argue that those with high incomes and significant wealth should not pay more tax overall to finance the public services we all use. But the danger of pursuing this end through a flat-rate pension contribution allowance is that it is both unfair in principle on those with high incomes, for the reasons outlined, and also that it needlessly complicates the tax system.

Some pension savers who make contributions out of taxed income get an HMRC rebate to their pension pots. But the contributions of many British workers are simply deducted from their gross monthly pay packet and paid into a workplace scheme before income tax is collected by their employer on the remaining balance – an arrangement known as “salary sacrifice”. This removes the need to calculate the specific rate of relief allowance for each saver.

If the Government were to impose a flat rate of relief, many employers would presumably have to deduct a new slice of tax from all of their higher-rate employees’ contributions and hand the money over to HMRC. That would be an odd move indeed for a Government that claims it wants to alleviate the burden of bureaucracy on business.

Or ministers might instead choose to ban salary-sacrifice schemes, which would be disruptive for many companies.

For those lucky people in final salary workplace pensions – destined to enjoy a guaranteed retirement income as a fixed proportion of their final salary – the technical complications arising from flat-rate relief would be even more horrible. Unless, of course, final salary schemes are simply exempted from these reforms – which, again, would hardly be fair. Such pensions are already much more generous than most people can hope to receive.

There is another danger. Fiddling with pension-saving incentives also risks changing the behaviour of high-income savers in unhelpful ways. If someone on a large salary finds putting money into their pension less financially attractive, they may well decide to plough their savings into the “safe bet” of residential property instead, pushing up house prices still further. That’s the last thing the country needs.

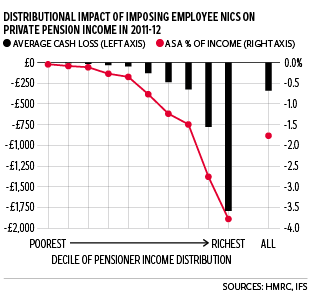

As the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has pointed out, if ministers want to raise more money from the pensions of the well-off, they should be looking at two areas: first, at the national insurance exemption on employers’ contributions to a worker’s pension scheme; and second, at the fact that anyone can take a quarter of their entire pension pot entirely tax-free on reaching the age of 55.

These allowances really do represent a free gift from the state. And because the rich will have bigger pots, they get a much bigger benefit. Those who want to tackle iniquity in the pensions system should be focusing their energies on this area. The IFS has said that imposing national insurance on pension income when it is paid out could raise substantial sums, with the wealthiest bearing the largest burden. And capping the permitted tax-free lump sum at £42,000 could bring in around £500m a year.

But politicians are a cynical breed. They have most likely targeted pension contributions relief in recent years because relatively few grasp how the system actually works. The widespread belief that the current contribution relief rates are “unfair” is similar to the public misapprehension that corporation tax is a levied on revenues (rather than profits) or that companies’ capital investment allowances represent a form of public subsidy.

Politicians should be busting these kind of myths. Instead, at least in the case of pensions contributions relief, they seem to want to exploit the confusion to raise cash. However, plucking the goose in this way inflicts damage on the efficiency of the tax system – and with no enhancement to the social fairness that they profess to care about.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments