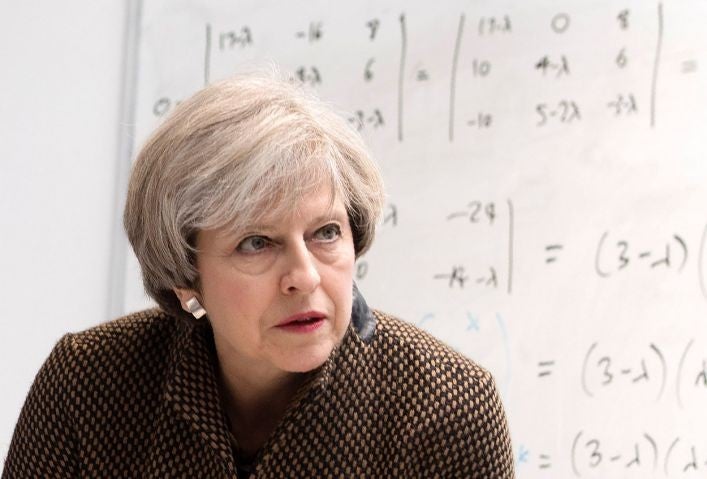

Grammar schools are pointless when millions of children are still living in poverty

Wear rose-tinted glasses by all means, Theresa May, but forcing selective schools to take pupils from poorer backgrounds will not solve the cost-of-living challenges they face

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Theresa May argues in favour of grammar schools – having attended one herself – and believes that it’s the government’s role to encourage aspiration and academic excellence in education. There’s nothing wrong with that, but to ignore the context of aspiration and achievement among lower income pupils is naive.

More than 3.5 million children are living in poverty in the UK and studies show that one in five parents struggle to put food on the table, with every indication things will be getting worse rather than better.

Learning and academic success are just about the classroom. If you are cold and hungry at home, it’s much harder to complete your homework, you’ll be tired in class and you are more likely to be reprimanded by teachers for not paying attention, which doesn’t do much to fuel enthusiasm.

It’s hard to have aspirations when you are in danger of being made homeless or are malnourished because the only hot food you eat is during term-time when you qualify for free school meals. Applying to university seems a million miles away when you come from a poor background and are faced with the prospect of getting £50,000 into debt with no guarantees of a job at the end of it.

Success at school is down to a number of factors: dedicated teachers who motivate, inspire and nurture; facilities and teaching methods to gain the academic and creative skills needed for the world today and tomorrow. Also needed is a positive environment, culture and peer experience that is inclusive both in and outside the classroom. Arguably if you are from a poorer background it is more difficult to harness these things. This impacts motivation and capacity to learn, even among the brightest of pupils. According to the Institute of Fiscal Studies over a fifth of pupils entering grammar schools come from non-state primaries, which alludes to middle class families sending their children to private primaries and getting “secondary education on the cheap”.

What the study didn’t expand on was the intangible cultural connotations of being a child from a poorer background at a grammar school. It’s tough fitting in as a poor kid in grammar school when most of your fellow peers are from middle class backgrounds. Snobbiness exists and you are often judged, not by who you are but by what your parents do. Extra-curricular activities and school trips are unaffordable and you feel isolated from missing out on these experiences.

Being a poor kid at grammar school made me incredibly socially aware in a way that I never was when I attended a secondary modern. I probably first identified as being a socialist while at grammar school, although probably on a subliminal level.

In order to be aspirational you need to have your basic survival covered, everything else is secondary and no amount of new grammar schools and forcing of selective schools to take pupils from poorer backgrounds is going to resolve this.

Successful educational attainment and social mobility is just part of the picture, and school experience is just a component. Until we consider it in relation to other areas and provide solutions that genuinely help and are not generated by meaningless statistics that suit a divisive government agenda, social mobility will not improve and getting into a grammar school will remain the least of poorer children’s problems.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments