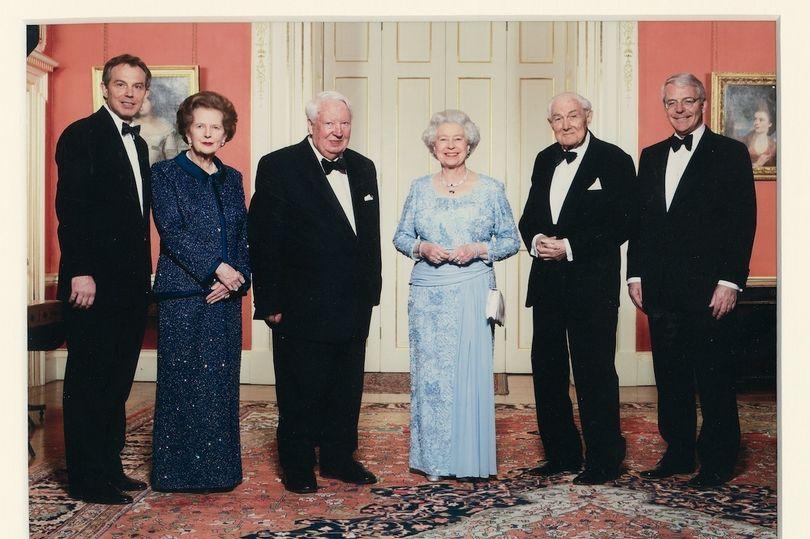

Our current politicians are nothing compared to the political greats of yesteryear – where oh where are they?

Has there really been a decline in the quality of people going into politics since the golden age, whenever that was?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Where are the greats of yesteryear? It is a familiar complaint. It was heard last week at the Peter Mandelson Memorial Dim Sum Supper, when my fellow diners surveyed the front ranks of all the main parties and found them wanting in credible leadership candidates as an alternative to the leader they have.

If Theresa May should announce that she is off to be head of development and community relations for a nuclear processing plant, as Jamie Reed, the Labour MP, did on Wednesday, who would take her place? Philip Hammond, probably, if there were an immediate vacancy. The Cabinet would nominate him as prime minister while a leadership election took place.

That election would probably be between him and a Brexiteer, either Boris Johnson or David Davis. Since the last leadership election, which didn’t even get to the final run-off stage, Johnson’s share price has drifted, while Davis’s has risen. Hard to say who would make the run-off, in which all party members vote, and who would win.

But the point being made by the dim sum prognosticators was that this was a thin field, and that the dearth of talent beyond the top three was a national embarrassment. As we scanned the other 19 members of the Cabinet, it was hard to identify possible prime ministers among them. Amber Rudd, maybe.

Even if we expanded what headhunters call our executive search to the ranks of non-cabinet ministers, and without wanting to name names that might stoke envy and division, there are few that seem to be cut out for the highest office.

The Labour side is no better. One of the causes of Jeremy Corbyn was the weakness of the field arrayed against him. Again, one does not want to cause trouble by imagining what would happen if Corbyn decided to become head of development and community relations for a wind farm, but it is not obvious that there is anyone with the charisma to bridge the gap between the idealism of the new members and the pragmatism of the ones who understand politics.

As for the Scottish National Party, you do not have to support independence to recognise that Nicola Sturgeon is an exceptional leader, and let us leave Ukip and the Lib Dems to one side for the moment.

The question, though, is whether it was ever thus, or whether there has been a real decline in the quality of people going into politics since the golden age, whenever that was.

It is a question prompted in part by Kenneth Clarke, who laments in his memoir, Kind of Blue, and in his talks to promote it, the passing of a politics run by people with hinterlands who understood cabinet government.

The trouble with hinterlands, which are generally measured in units of Denis Healey, Labour Chancellor and then deputy leader in the 1970s and 1980s, is that they tend to be attached to people who never quite made it to the top.

Healey, who had been a captain on the beaches of Anzio in the Second World War, knew his literature and could write, but he was abrasive in politics and his son says, disloyally, that he would have made a terrible prime minister.

Another more recent example: William Waldegrave. He was a clever and diffident cabinet minister under Thatcher and Major, who last year published a brilliant memoir, highly learned and beautifully written, about his demented ambition to be prime minister and how it was frustrated by the widely forgotten inquiry into the sale of arms to Iraq in 1996.

Today’s conspicuously hinterlanded politician is the Foreign Secretary. The other day, when he was asked if he would take up Tony Blair’s offer to help with Brexit talks, he said: “Non tali auxilio, nec defensoribus istis.” Latin for “You must be joking”.

Perhaps that means he, too, will never make it to the top job. But you cannot tell. He would probably be prime minister now if his friend Michael Gove had not suffered from a bout of demented ambition himself.

One of the advantages of Tim Shipman’s excellent account of the referendum campaign and the Tory leadership turmoil that followed, All Out War, is that we have an instant history of great events and the parts played in them by people who are, whatever we think of them, of historic stature.

So I don’t hold with golden-ageism. Just as I take with a pinch of salt Kenneth Clarke’s portrayal of Thatcher as the model of collegiate cabinet government. I remember thinking when Tony Blair started out, Bambi-like, in his campaign for the Labour leadership, how fragile he and the operation around him seemed. It looked as if it could all collapse at any moment and Michael Heseltine would be prime minister for ages.

That is why I am sceptical about a lot of the gossip about Theresa May: how unsuited to prime ministerial office she and her close advisers are. A lot of it is a proxy for disagreement. Remainers don’t agree with leaving the EU and so they think anyone who wants to leave the EU (especially if they didn’t, on balance, before) is hopelessly disorganised and hasn’t got a plan.

And that is why we shouldn’t despair about the quality of recent intakes of MPs. Maybe what has changed is that politics is faster now, so it may seem harder to identify talent, partly because that process has to happen more quickly too.

It may look as if political talent is thin on the ground. But perhaps it is just that we haven’t had time to identify the greatness yet.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments